The Stunning Stitcher

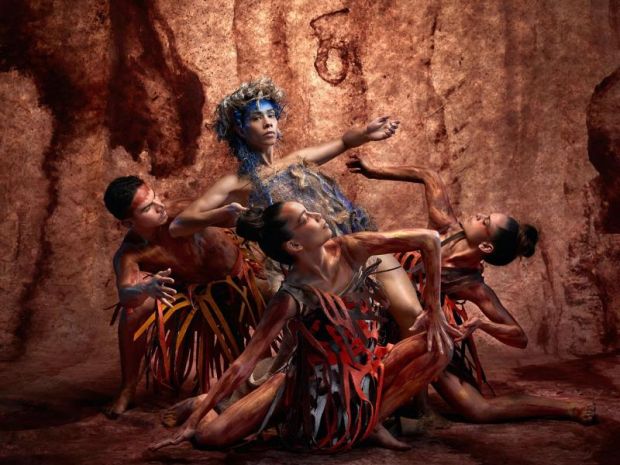

Image: Yuldea. Photographer: Daniel Boud

JENNIFER IRWIN is Australia’s most applauded costume maker – adding to decades of recognition with yet another recent award for her work with Bangarra Dance Theatre. Martin Portus explores what’s made her creations the perfect fit – especially for dancers.

She was a shy girl at Pymble Ladies College but loved lipstick and dressing up and so, thirsty for life, she escaped home to study applied arts in Wagga Wagga. Australia’s applauded costume designer soaked up more inspiration in 1980 at Adelaide’s new tech arts course, and stayed on just as the city’s dance and theatre scene was blossoming. She “helped and picked up” costumes backstage, often unpaid, but Jennifer Irwin was soon trading on her special sewing skills.

Back in Sydney, upcoming choreographer Graeme Murphy nabbed her as a costume assistant, soon supervisor, for his embryonic dance company.

Back in Sydney, upcoming choreographer Graeme Murphy nabbed her as a costume assistant, soon supervisor, for his embryonic dance company.

“Graeme was already making a name for himself,” says Irwin. “But we worked in a complete dive, a crumbling squat in Woolloomooloo where the Housing Commission kids used to break into our cars and rob buildings; like it was pretty wild, with just one shower for all the dancers.”

But Irwin was busy perfecting another of her signature costuming skills: how to make sheer gossamer body stockings which, while strikingly adorned, fully reveal every muscle of the dancer. So began her long and outstanding creative association with two of Australia’s dance landmarks – Graeme Murphy’s Sydney Dance Company and from 1992 Stephen Page’s Indigenous Bangarra Dance Theatre.

Image (above): Jennifer Irwin with a costume from Bangarra Dance Theatre's Dark Emu. Photographer: Daniel Boud.

Her first chance to actually design SDC costumes was Sirens, Murphy’s homage to ten famous women, right at home at Kinselas, the happening nightclub on Oxford Street. She then created high impact costumes for Shining, Murphy’s lyrical hymn to hedonism which from 1986 toured the world. By this time the company was smartly housed in Walsh Bay and Irwin was irreplaceable. She not only made all her own costumes but also those of other designers sometimes chosen by Murphy for more character-filled dances.

Over decades, she’s designed costumes for 33 SDC shows, 37 Bangarra dances and nearly 20 major ballets, always with a fresh vision, sculpturing new design ideas from new technologies and fabrics. She was commissioned for the opening and closing ceremonies of the Sydney 2000 Olympics and her work has been staged live in more than 90 countries.

Irwin also designed the world premiere in Sydney of the musical classic, Dirty Dancing. Twenty years later it continues today to travel the globe and – unusually for Australian creatives working at home on big musicals – she still gets royalties.

Image: Bangarra Dance Theatre's Sandsong Stories From The Great Sandy Desert (2021). Photographer: Daniel Boud.

“Dirty Dancing really allowed me to survive in this industry,” she says. “Working in the arts you might be very good, at the top of your profession, but it doesn’t make you a lot of money; it was very unusual for someone like me working in subsidised live performance to get that job.”

As a jobbing creative, Irwin must be inventive to find new work options and, in her coastal retreat north of Sydney, says she’s nervous at the idea of retirement. Those skills at sewing, cutting and making her own costumes, especially those bodysuits, won her gigs on The Lion King and movies like Wolverine, The Matrix and Mission Impossible, and are vital to her survival.

“If I may say so, I make the best bodysuits – I can do it with my eyes closed. If you can cut dance costumes you can make action costumes to fit perfectly on any body. I do all the stretchwear for Opera Australia.”

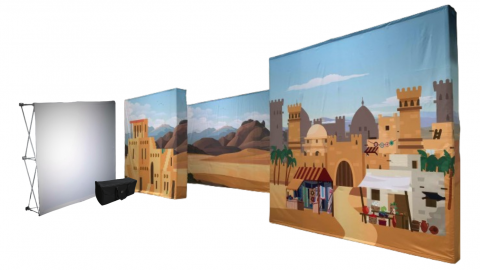

Image: Guys and Dolls - Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour. Photographer: Neil Bennett.

Image: Guys and Dolls - Handa Opera on Sydney Harbour. Photographer: Neil Bennett.

Vital to Irwin’s success is her hardworking loyalty to a small band of prestigious companies who keep coming back. She’s now rethinking the 1950s as costume designer for Guys and Dolls, which Opera Australia is opulently staging on Sydney Harbour in March. Shaun Rennie has taken over as director after the sudden resignation of the company’s artistic director Jo Davies.

No wonder Irwin’s awards collection is so big. She’s created costumes for 18 Helpmann award-wining stage productions and has a swathe from the Australian Production Design Guild, which last year recognised her with the award for Outstanding Contribution to Design. She has ten further APDG nominations, and in August 2024 won Best Costume Design for her work on Bangarra’s Yuldea.

Yuldea was the first production by Frances Rings as Bangarra’s artistic director following the departure of founder Stephen Page. It drew on colonial episodes of environmental devastation as experienced by the people of the Western Desert of South Australia; Rings’ own country is adjacent in SA’s south west.

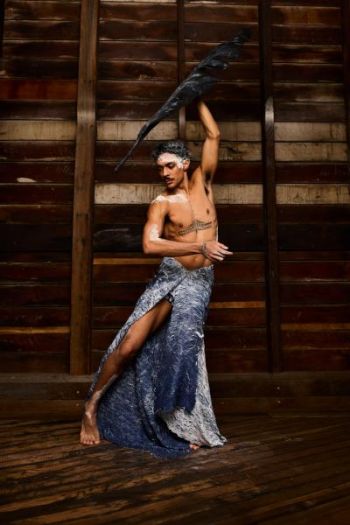

Irwin also designed an earlier, abstract work by Rings, Terrain, inspired by Lake Eyre, the dancers distinguished by Irwin’s sprouting feathers, clusters of leaves and headdresses of spinifex and sprays of twigs. Her costumes so often look like she’s been out in the desert picking up nature, but no she hasn’t.

Image: Yuldea. Photographer: Daniel Boud.

“I’ve never used a leaf, or any real feathers, but I’ve made plenty! And I don’t usually go out on country.”

Bangarra’s first big hit was Ochres at Sydney’s Enmore Theatre, where the company found a keen new audience in 1994. And Irwin learnt heaps about how the different colours of ochre which Bangarra dancers paint on their bodies soon become an organic part of her costumes.

“It’s a nightmare but it’s terrific. I look at costumes as something that will disintegrate over time, but actually they get better, because ochre you can’t wash off, especially the red. So the costumes get layered and layered from ochre on their bodies, often head to toe, and on the floor – they and the stage become an art work. We often put talcum powder on the costumes which gave them an initial puff of smoke, an added spiritual touch! That evolution of costume making as the dancers wear it and make it their own wouldn’t be possible with any other company, dance or theatre.”

Image: Bangarra Dance Theatre's Terrain (2012) Photographer: Greg Barrett.

Bangarra has gone on to create exemplary production standards, with inventive composers like David Page and Steve Francis and Jacob Nash’s stunning abstractions of landscape. It’s all a long way from the set of Ochres – “it just had a little mound,” laughs Irwin.

She’s always worked alone, with a glimpse perhaps of a set design, but often without Stephen and the company seeing her work until dress rehearsal. “They trust me,” she says. “And they’re running around doing their own things.” Later came early meetings of the creative team, Stephen had clearer initial ideas, and the set was built earlier, but Irwin still had challenges.

“When you’re working with dance you’re building and making costumes as it goes along, because choreographers have an idea, but only in the process does it unfold – and change! So with the SDC and Bangarra, I always started with the presumption the dancers have to be free to do anything, and will always end up on their knees because the works are so grounded. Now we have developed a design shorthand - I think we actually see the same images when we are talking together.”

“And over the years I’ve educated myself. As a non-indigenous person, I have to be careful; I basically give them a costume which is abstracted from traditional Indigenous, but I would never go to that source. I’d ask an elder for something like a feather string, but never make that myself. I would use textures or weaving but it’s not traditional in any way, just suggestion.”

Stephen Page was barely out of his teens as a dancer when Irwin met him at Sydney Dance Company, the first big salaried job for both of them. And she designed some of the first works he choreographed there.

She’s very excited that decades later they’re soon both returning to the SDC to create together a new work for September 2025.

Irwin has worked with Stephen and his team from the very start of Bangarra, through the tragic deaths of his brothers and collaborators: Russell on the opening night in 2002 after he so beautifully danced a solo in Walkabout, and David in 2016, the effusive composer who created Bangarra’s signature mix of traditional, language and natural sounds with contemporary rhythms from around the world.

She’s also watched – and shifted her costuming approach – as Stephen Page this century took on more historic contact stories of both black and white Australia. It began with Mathinna, about the Aboriginal girl adopted then abandoned by Tasmanian governor John Franklin; then Patyergarang about her language exchanges with Lieutenant William Dawes in colonial Sydney; and Bennelong, a witty yet often horrific pageant of scenes from the Indigenous and settler life of Governor Phillip’s chosen black “ambassador”.

Irwin of course did thorough historical research into the period costumes required for these increasingly extravagant and compelling dance theatre works. The biggest was Page’s final major work for his company, Wudjang: Not the Past, an epic story of pre-settler and contact scenes in Australia collaboratively told by dancers, musicians, singers, actors, designers – and Irwin’s inventive costumes for them all.

“I think Mathinna was a turning point where he drew from historical stories, all with the sanctioning of the clan Elders of the stories given over,” says Irwin. “Maybe it was because Bangarra had by then become so much respected and was now in a position to be custodian of stories that needed to be told … the stories of Mathinna, Patyergarang, Bennelong, all names that we know but this is their real story from an Indigenous perspective.”

Jennifer Irwin naturally jumped at the chance to get the band back together, when last January at the Adelaide Festival they created Baleen Moondjan, Page’s first commission since Bangarra. Set on Glenelg beach, within Jacob Nash’s enormous whale carcass, to music by Steve Francis, these were tales of Baleen whales passed on to Page by his mother. And critics praised the costumes.

Irwin in 2024 herself was also back with Bangarra for The Light Inside – Horizon collaborating with New Zealand choreographer Moss te Ururangi Patterson on a striking work of Maori landscapes, coasts and lakes, the dancers draped in her ephemeral autumnal-shaded cloth.

“Terrain with Frances in 2012 was a turning point for me where my work became more sculptural. I took a leap of faith, really exploring what fabric could do, pushing it further. Possibly my most recent works have been my best. Working with choreographers and directors who trust your input always gets a better result. But The Light Inside was not that experience for me.”

Indeed, after decades helping to forge the design aesthetic of Bangarra, Irwin thinks this will be her last show for the company.

“I have mentored my young Indigenous designers and now it’s time to step back, whether I want to or not. It’s definitely time.”

Meanwhile she’s happily worked with her other great collaborator, director Graeme Murphy, on a sumptuous touring production of Opera Australia’s The Merry Widow and a revisionist Madame Butterfly.

“In absolute contrast to Bangarra, Madame Butterfly is a white story in Japan that some argue should not be told in this day and age. Graeme wanted a contemporary approach. There was much conversation about where she came from, working as a geisha girl and about the ancient arts of Shibari/Kinbaku rope tying. My costume designs are always informed by the set, so MB became very architectural and clean cut. I focused a lot on the art of origami using a lot pleating, abstract and structured.”

She’s designed significant stage productions for the Sydney Theatre Company and Belvoir and knows well the added responsibility of placating actors keen to discuss character in the making of their costume. Dancers are less concerned.

But Irwin is pessimistic for the future of her profession, with jobs so scarce today for an ever growing surplus of talented designers, and performance companies which save money by employing designers to do both set and costumes.

“It’s a young person’s industry, so very hard to make a living financially. Australia just doesn’t have the population to support the numbers of people coming out of colleges every year. But as a young designer you live the dream, working from one show to another. Designing for film is better paid but everything revolves around money rather than the product and rarely do you get the opportunity and that freedom of live performance design.”

Yet somehow, without relying on film, Jennifer Irwin continues to build her outstanding legacy in costume design, and even in the niche and competitive world of dance. She’s achieved the dream she had as a shy little kid who made shoes by tracing her foot on cardboard and attaching empty cotton reels for the high heels.

“I love my job. I’ve always loved the adrenalin race to get the show on – a collaboration of everyone working together – to finish, before the curtain goes up.”

This article draws partly on an oral history interview with Jennifer Irwin by Martin Portus available online at the State Library of NSW.