A Streetcar Named Desire

‘What you are talking about is brute desire – just – Desire!’ says an incredulous Blanche when her sister Stella explains why she stays with her abusive husband. Yet she could be talking about our need for intimate theatre in Adelaide, lamenting the imminent closure of the wonderful Bakehouse Theatre.

Opening night of a new production has any theatre foyer buzzing, but for this, the final opening night of any kind in this venue, the atmosphere is subdued. Masked as we are, there appears little difference to the recent, repeated returns to theatres in a pandemic, but we stand more solemn with our glasses of alcohol, torn between the fantasy of the theatre and the real lives beyond the foyer doors.

Much like Blanche DuBois then, escaping her reality of a disgraced schoolteacher to experience a new fantasy here, in Elysian Fields. Tennessee Williams’ classic social and moral tale from 1947 examines the struggles of living across the boundaries of two worlds: the old and new, the real and fantastic.

Blanche steps off a New Orleans streetcar, disbelieving that her sister Stella should now live here, instead of their now-lost family Mississippi homestead, Belle Reve (‘beautiful dream’ in French). Stella is married to Stanley Kowalski, American-born from Polish parents, and they reside in a two-room apartment. A small group of friends bowl together, play cards together, and live on top of each other – and Williams’ story of life, death, domestic violence, the role of women, and society’s responsibilities, is told across a few weeks in this single, intimate location.

For this final show, the Bakehouse’s own Pamela Munt has assembled a brilliant production, with a stellar (!) cast and crew: Melanie Munt (Pamela’s daughter) is astonishing as Blanche, bringing a character to life through her self-centred words, swaggers and stumbles; utterly convincing as a victim of trauma: her eyes dancing in her fantasies of confidence, yet lifeless when reality interferes.

Justina Ward is no less impressive as Stella, Blanche’s sister, who escaped the family home before it was lost through their ancestors’ actions. Ward demurs when Munt’s Blanche asserts as the superior sibling yet shows fire in her belly when insulted. The range of both Munt and Ward is really on show here – both emotionally and physically: this is an aggressive performance in both word and deed and these two actors flow together, bounce off each other, never dropping who they are.

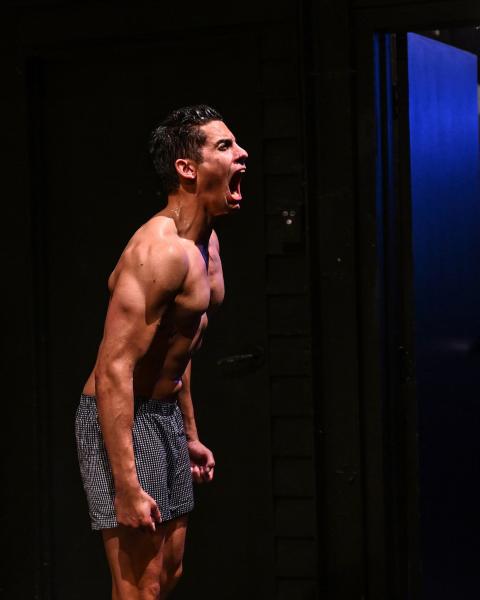

Paul Westbrook injects Stanley with so much energy – he’s fierce and proud as a Pole, as a man supporting his wife Stella, and as someone with a deep distrust for those that hide behind lies and omission. ‘I don’t like to be swindled.’ he says with a vigour barely contained by Westbrook – indeed, when he explodes, it’s still shocking, even when you know it’s coming, and Westbrook is terrific when Kowalski is toxic.

Mitch is played with more subtlety by Marc Clement, who doesn’t get his usual moments to shine in the Bakehouse spotlight simply because he’s shadowed by the immense talent around him. His earnest portrayal of a man walking the edges of sensitivity and masculinity is great, and his simmering anger is frightening.

Susan Cilento (Eunice) and Nathan Brown (Steve) round out the excellent regulars on stage, with Matthew Adams’ scene as a young man with Blanche a rare moment of light relief. Cameos from Bakehouse proprietors Pamela Munt and Peter Green are welcome, even in the depths of tragedy.

Director Michael Baldwin creates stunning compositions with his actors across the full stage (and up the auditorium steps and into the theatre’s foyer), steering his engaged and talented cast through Williams’ grimy dilemmas with deliberate ambiguity: he doesn’t try to signal a correct answer, instead shows us the agony of alternatives – and it works well. It doesn’t need nudging for us to draw parallels to today’s still-present re-asserting patriarchy, hidden domestic violence, and the gulfs between our lives played out on social media versus reality. Williams’ themes remain vitally relevant, and Baldwin doesn’t downplay any of them. He preserves the complexities of each character’s narrative; the language and violence remain confronting.

The set from Andrew Zeuner and David Dyte is beautiful: furniture that was once nice now tarnished or mismatched, the two-room apartment and outside step simply divided by two door frames; the light from the theatre’s foyer deliberately spilled through to give us a glimpse that there is life beyond (or before) Elysian Fields. Stephen Dean knows how to light every inch of this building. Stage management (also Zeuner) is always going to be challenging given how much cleaning up of broken things there is to do in the dark, but it never lets the pace drop.

The soundscape of braking trains and squealing cats never lets us forget the city but there is also a hero in the pianist, Walter Barbieri (to be replaced by Brendan Fitzgerald in the second week). His music stitches the action together, provides a theme for Blanche through which she relives her trauma, and together with the authentic looking sweat on the performers’ clothes, keeps us in the hot Louisiana state.

At the end of the play, just before the stage lights fade to black at the Bakehouse Theatre, Eunice’s philosophy seems to be a plea to these last audiences, as she implores: ‘Life has to go on. No matter what happens, you’ve got to keep on going.’

Mark Wickett

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.