The Sound Inside

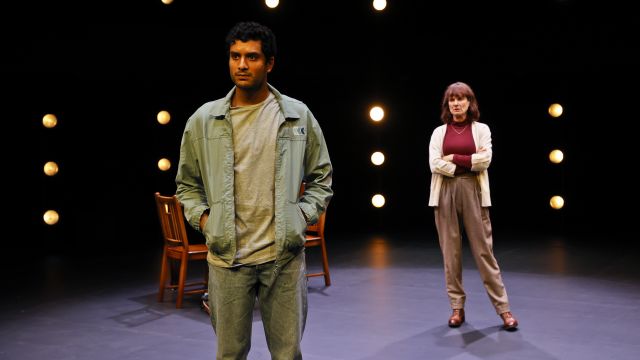

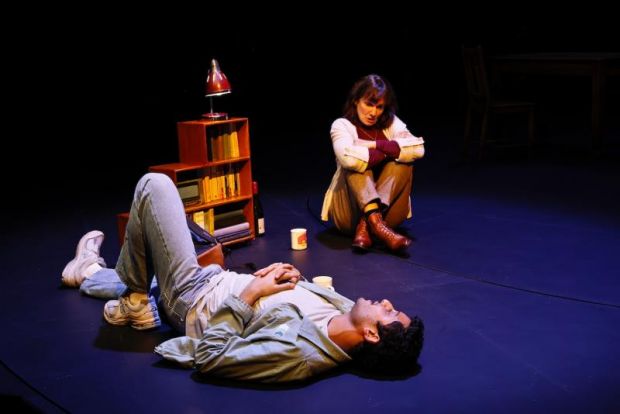

The Sound Inside is a story of two outsiders, a fifty-something tenured creative writing professor at Yale, Bella Baird (Catherine McClements), and her bumptious, opinionated student Christopher Dunn (Shiv Palekar).

Anyone who has been a teacher has had a student like Christopher. They are so frustrating because so often one glimpses the high intelligence, sensitivity, and talent behind the apparent arrogance. Bella is irritated by Christopher’s arbitrary defiances (he won’t make appointments, just shows up, won’t use email and he loathes Twitter) and he’s a mass of petty – if amusing - prejudices.

The Sound Inside is a small gem. A gripping, intimate chamber piece, it plays out on an almost bare space – except for a lonely streetlamp. It is a twists-and-turns thriller and a psychological study of people who revere and create fiction in the written word - and about themselves.

Christopher is something of a traditionalist – and so is she. She is intrigued when he speaks for the first time in her class; he boasts that one day he will write a scene as good as the murder scene in Crime and Punishment. When they discuss ‘good writing’, they share the same principles and admirations. Dostoevsky and Crime and Punishment are key – although their tenets of fine writing sound more like Turgenev. Both admire John Salter. Character revelation via literary judgement. (Yes, you may get slightly more out of this play if you are an avid reader yourself.) And Bella becomes the more intrigued when Christopher confesses (and it is pretty much a confession because he is, of course, wracked with doubt) that he is writing a novel…

Playwright Adam Rapp takes a number of risks here. First, we have two highly intelligent, highly articulate people who talk about themselves and about writing. Second, there is the story (Christopher’s novel) within the story – a device, like the-film-within-film, that can be a mistake, a token, straining our belief in the talents of the storyteller character. Not so here. Adam Rapp himself is a novelist as well as a playwright and screenwriter and he makes us believe that Christopher can write – or that Bella believes he can write. Christopher’s novella, as Christopher tells it, and as Bella reads it – not word for word – we get a kind of summary - is intriguing, cleverly structured, and shocking. When it is shocking, Bella doesn’t turn a hair – as if she only cares about the quality of the writing, as writing.

And then there is a great deal of telling rather than showing. The bulk of the play, in fact, consists of Bella telling us stuff. Not only does the play begin with a long monologue from Bella about herself, but she also continues to tell us stuff throughout the play, interrupting scenes in which she and Christopher interact – so as to summarise parts of the conversation. She does that of course because she’s a fiction writer too - a writer who turns life into fiction. Catherine McClements’ lovely performance enhances Bella’s amused-at -herself, self-deprecating, unsentimental revelations – and we never get tired of her telling us stuff. In fact, we come to love her. For instance, this from her opening monolgue:

Like many single, self-possessed women who’ve managed to find solid footing in the slippery slopes of higher education, I’ve been accused of being a lesbian. And a witch… and a collector of cat calendars.

Shiv Palekar’s Christopher is an excellent performance too, providing a sharp contrast to McClements’ slight stature, wit, and delicacy. His Christopher is blunt, socially clumsy, and hulking, verging on threatening. The gradual seeking out and coming together of these singular characters is emphasised, made visible, via director Sarah Goodes’ stage direction. Her imaginative use of spaces on the stage is a hallmark of her work. Here, with this near bare space – and the absolute minimum of props – she uses the two revolves, outer and inner, to show us two character circling each other, but she does that so appropriately and unobtrusively that we concentrate only on the characters – not the director’s means of showing them. (Design is by Elizabeth Gadsby, realisation Jo Brisco, lighting by Paul Jackson.)

I cannot say more about the plot of this beautifully crafted but rule breaking play without spoiling the surprises and revelations that follow. What is ‘the sound inside’? The play will tell you – but it is something to which we should listen.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Jeff Busby

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.