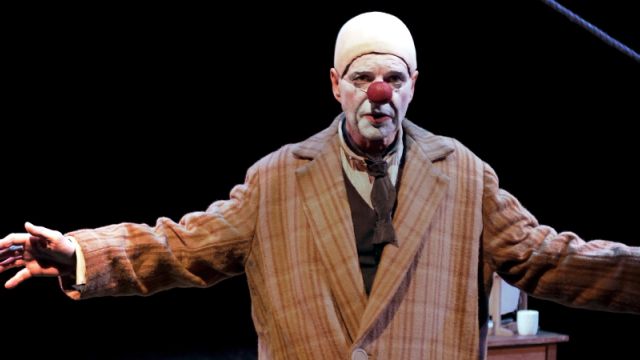

Scaramouche Jones

There is nothing in theatre more powerful than an actor at the pinnacle of his performing ability, seamlessly melding art and craft to perfection: Colin Friels is that actor. He and Justin Butcher’s Scaramouche Jones come together at a moment in both their lives where they truly connect, and it’s a theatrical marriage made in…well, you know how clichés go.

To call Butcher’s play a monologue or a one-man play is a misnomer, particularly with Friels in command. There is a myriad of colourful characters, all brought to life in three dimensions by the actor as he tells his, or rather, Scaramouche’s story. We don’t just hear and see these pivotal people as ghostly recollections, we meet them as flesh and blood human beings, flawed and seeking salvation. Each has its own voice, stature and body language.

Whilst Butcher’s play is ostensibly a trip through the life of a burned out clown, a man turning 100 as the clock strikes the beginning of a new millennium, it is, at heart, a history of the twentieth century; of the best and worst of mankind; of hope and survival against any and all adversity.

Thus the white faced “oyster” that slips from the womb of a prostitute in Trinidad, never knowing his “Englishman” father, endures being sold into slavery, becoming a snake-charmer’s assistant; an unconsummated marriage to a 12 year old gypsy girl; a period in a monastery, and even grave digging in a concentration camp where he hones his clown skills to put children about to be executed at ease and laughing while facing death. His efforts result in him being charged with war crimes.

Finally, he prepares to face the moment of his centenary, and all of the masks must come off to allow for a new world, one in which he has no place. When he tells us of his seven masks - each layer hiding another level of scars - it is reminiscent (by design) of Shakespeare’s Seven Ages of Man speech from Act II of As You Like It. But whilst that monologue is told objectively in the third person, the old clown lives and breathes every moment behind every mask.

Finally, he prepares to face the moment of his centenary, and all of the masks must come off to allow for a new world, one in which he has no place. When he tells us of his seven masks - each layer hiding another level of scars - it is reminiscent (by design) of Shakespeare’s Seven Ages of Man speech from Act II of As You Like It. But whilst that monologue is told objectively in the third person, the old clown lives and breathes every moment behind every mask.

The play was originally made for Peter Postlethwaite – a lovely actor – and I saw his performance in 2003. But where PP gave us poetry, Friels gives us humanity, where PP was ethereal, Friels is all earthiness, flesh and blood, and shows us (not just tells) what it is to truly endure all it means to be part of the human race and not give up. It’s a profound and moving performance that is greater than the play itself. It’s full of self-awareness without self-pity; truth without recrimination; acceptance without surrender. It is the measure of a man…and an actor. He’s a man, and an actor, who has met death and stared it down but is conscious of aging and his own mortality. I’ve seen Friels “dry” on a single line, and yet he handles this complex text, which is often rambling, as if it is stream of consciousness, an instant truth, and on the couple of occasions where the text momentarily eluded him and he went back on a line, it was as if an honest lapse of the character’s memory was being searched for - it’s also a very physical role and one could see where the 100 year old clown and the 67 year old actor shared a moment when age attacked their knee joints.

Director Alkinos Tsilimidos has worked with Friels before, but this time pushes him further than he did in the acclaimed “Red” some years ago at MTC. It pays dividends, though there are odd moments where the blocking seems to do no more than add movement for its own sake, to avoid the “talking head” trap. Richard Roberts’ set is superb but minimalistic - and the space at HOTA - outdoors yet undercover (the space is UNDER the stage of the outdoor performing space) is perfect to suggest the circus. Matt Scott’s lighting is evocative, but some cues seem wrongly placed in the text and detract from subtextual intent rather than complementing it. But, in the end, it all comes back to performance.

Director Alkinos Tsilimidos has worked with Friels before, but this time pushes him further than he did in the acclaimed “Red” some years ago at MTC. It pays dividends, though there are odd moments where the blocking seems to do no more than add movement for its own sake, to avoid the “talking head” trap. Richard Roberts’ set is superb but minimalistic - and the space at HOTA - outdoors yet undercover (the space is UNDER the stage of the outdoor performing space) is perfect to suggest the circus. Matt Scott’s lighting is evocative, but some cues seem wrongly placed in the text and detract from subtextual intent rather than complementing it. But, in the end, it all comes back to performance.

We’ve lived with Friels’ talent for so long it is easy to feel his pain, as if he is a part of us, Everyman. He’s had a long career, some of it exemplary, some of it journeyman - often we are disappointed because we have expected so much, and wanted more. Friels himself has said he is not a great actor – but then he has never had the benefit of being in the audience to see his performance. I wish he could, then he would know, as those of privileged to see this play know, just how good he is.

Coral Drouyn

Photographer: Lachlan Bryan,

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.