The Rite of Spring / common ground[s]

In common ground[s], two mature and esteemed women command the stage; one with dark skin, one fair-skinned, both clothed in flowing, floor-length matte black gowns. Germaine Acogny & Malou Airaudo are both now in their seventies but move with enviable fluidity, strength and depth of expression. Airaudo was one of the formative dancers at Pina Bausch’s Wuppertal Dance Theatre from the early 1970s and is still a revered teacher and choreographer. Senegalese dancer and choreographer Acogny, known as the mother of contemporary African dance, established her first studio in Dakar in 1968, then in 1997 established the International Centre for Traditional and Contemporary African Dances, L'Ecole des Sables. Acogny's background in traditional dance can be traced to her grandmother, a Yoruba priestess, and her work is significant for the way it combines contemporary with traditional dance.

common ground[s] is co-choreographed by Acogny and Airaudo blending their shared wisdom of dance and life, emanating a deep sense of woman’s inherent nobility. First seen silhouetted and seated against an orange cyclorama, perhaps dawn, perhaps sunset, there is a cooperative section involving a long rod which both links the women and their cultures and supports them in their tasks. The two women traverse space with gravitas, in unison or mirrored movement, including tender duets and solos. Much of the gestural arm work ends or begins in an embrace or a stylized touch signalling stability and trust. There may be many interpretations of this piece but for me it honoured women’s work and ritual, female harmony and creativity, generational connection and a commitment to peace.

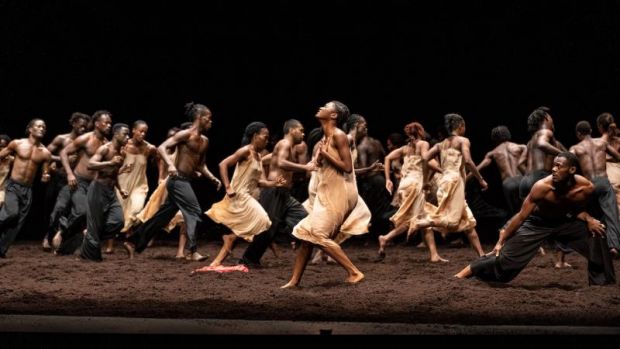

In preparation for Pina Bausch’s The Rite of Spring an impressive, efficient crew transformed Her Majesty’s stage during interval. By pushing back the wings and cyclorama and spreading dark brown peat over the entire floor, a cavernous, dark and threatening landscape was created to house the frenzy of this work where a sacrificial female eventually dances herself to death.

A remarkable artistic lineage is represented through this programme and the new staging of The Rite of Spring - forgive the ‘dance nerd’ in me: Malou Airaudo originally danced the lead for Pina Bausch in 1975; Acogny danced a solo in Paris in 2018 choreographed by Olivier Dubois - Mon Elure Noire (My Black Chosen One) - to Stravinsky’s score as a nod to her experiences with choreographer Maurice Béjart; Acogny also saw the production performed in 1996, when Bausch restaged it for the Paris Opera Ballet; in 1958 Bausch was briefly at Juilliard in New York and taught by Antony Tudor, who was taught by Marie Rambert, who danced with Diaghilev, who commissioned Stravinsky and Nijinsky to create an original work, both called Le Sacre du printemps; plus the remarkable and complex evolution of this entire project has involved dance personalities from all over Africa, and from Germany and England.

Le Sacre du Printemps was Stravinsky’s third major project for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes 1913 Paris season, after the acclaimed Firebird (1910) and Petrushka (1911). Famously, the work was said to have caused a riot when first staged due to a combination of the exotic choreography, Nicholas Roerich’s bizarre design, the pagan references and the shock of the music itself. The score contains many novel features including experiments in tonality, metre, rhythm, stress and dissonance. Musical theorists have declared the score to have a significant relationship to Russian folk music, although Stravinsky denied this.

Acogny states that she found the rhythms relatable to an African rite when she first heard the Stravinsky music. She also believed that dancers of African heritage should perform the work because of its universality. There is definitely a primal energy ingrained in The Rite of Spring and this collection of dancers do it remarkable justice. The mix of sweat and soil flying alongside the dancers’ bodies as they interpret the music and the visceral abandon of the choreography energetically combine to create a mesmeric whole.

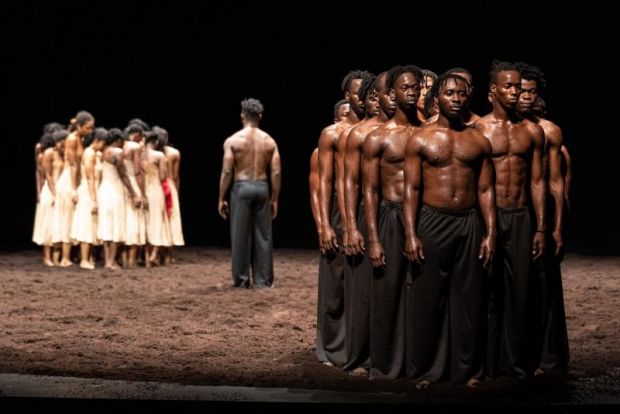

Like Nijinsky, Bausch followed the rhythms of the music to perfection. It is as if the music drives and determines the powerful movement which includes body percussion and rhythmic spinal contraction and release plus dramatic falls to the floor and flailing arms and legs. Interestingly, circle shapes are used in the choreography which is also a feature of some African traditional dance. One impressive section sees the females flying through the air with total abandon to land high upon the bodies of men, other sections create divisions between the genders and still others amalgamate the entire company in spectacular unison dance. Here, the choreography is executed with passion and intensity so that a leap has meaning and purpose as opposed to simply being a ‘pretty’ technical feat.

The design remains true to Bausch’s original work with the women in flesh-toned slips, the men in dark grey trousers, and all of which become sweat- and soil-stained. The symbolic red dress is first seen as a scrap of fabric then eventually placed on one woman’s body as she is thrust into the sacrificial role. The simple design allows the dance to dominate exemplifying how emotional force and unmediated physicality became traits of Bausch’s work as she coalesced all the influences she had inherited from mentors, teachers and fellow practitioners.

The entire evening’s presentation was of the highest calibre and most definitely Festival fare. It is unlikely we would be treated to an event of this size and complexity at any other time. Bravo.

Lisa Lanzi

Photographer: Andrew Beveridge.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.

![The Rite of Spring / common ground[s]](https://www.stagewhispers.com.au/sites/default/files/imagecache/preview/reviews/The%20Rite%20of%20Spring%204_Photo%20by%20Andrew%20Beveridge.jpg)