Orson’s Shadow

Austin Pendleton is an American actor, director and playwright who has a vast experience in both stage and film across a variety of genres – with a variety of actors, some of them very famous. That sort of experience informs this play, first performed in Chicago in 2000, where he brings together two great stars of stage and screen – Orson Welles and Sir Laurence Olivier – and their egos and vulnerabilities.

The play begins in Dublin in 1960 where Welles’ production of Chimes at Midnight is failing dismally. Enter ambitious theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, who convinces Welles to leave Dublin to direct Olivier and Joan Plowright in Ionesco’s absurdist play, Rhinoceros. Wait a moment … that’s a pretty unlikely plot.

Olivier in a modern play, especially one where all the characters turn into rhinoceroses?

Welles coming out of ‘self-exile’ after the perceived failure of Citizen Kane to direct Olivier?

Both great men well past their artistic prime?

Plowright just emerging – and Vivien Leigh slipping fast from favour?

And a theatre critic having the cheek to suggest it?

Only someone with Pendleton’s theatre experience could pull off. It’s an insider’s interpretation of how the two great stars may have interacted – and how Olivier may have dealt with the dilemma of losing Leigh while gaining the younger and ambitious Plowright. It works – but what a challenge it presents to both directors and actors! Recreating real actors whose skill was recorded so vividly in many movies and whose lives were documented so intensely in many articles and biographies … It’s no mean feat!

But first-time director Josh Stojanovic courageously takes on the challenge of producing the Australian premiere of Orson’s Shadow. He does so with a resolute vision, a very committed and able cast and a busy crew. Stojanovic has worked closely with the script and his cast. Together they have found a way to identify the characters strongly without attempting to mimic or impersonate.

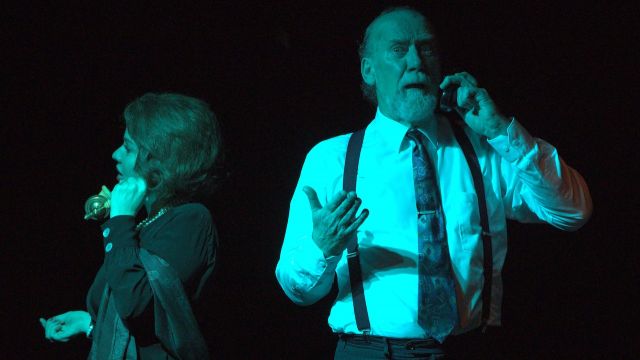

Christopher Bancroft is strikingly imposing as Orson Welles. Bancroft has a commanding stage presence which he uses to depict both the latent power of the noted actor and his diminishing self-belief. He uses gesture, pause and comedic timing effectively, creating a character that is confident one moment, insecure the next.

The aging Olivier is played by John Bailey, who cleverly portrays both the conceit of fame, and the anxiety of age, that Pendleton has written into the role. Bailey uses his lines to infuse his Olivier with arrogance, vanity and staged humility when relating with Welles – but apprehension and concern when dealing with Leigh and Plowright. This requires some difficult balance, but Bailey manages it well.

Matthew Doherty takes on the role of Kenneth Tynan, confident critic and, hopefully, National Theatre literary manager, if he can persuade Olivier of his worth. Pendleton has written in Tynan’s ambition, his growing problem with emphysema and his unfortunate stutter, and Doherty deals well with all of this as well as having to revert to narrator. He is confident and persuasive with Welles, less assured when dealing with Olivier, winningly open when speaking directly with the audience.

Marianne Gibney-Quinteros is a restrained and poised Plowright, confident in her conquest of Olivier and her own acting future. There is a lot of watching and listening in this role and Gibney-Quinteros does both realistically.

Cassandra Strasiotto has the delicious job of portraying the fading Vivien Leigh. At first she is the elegant Leigh in her home at Notley Abbey, surrounded by rich colours and talking reservedly on the telephone. Later, in person at the theatre, she allows that poise to dissolve into self- pity and emotional distress.

Providing a comic contrast to these highly strung characters is Shaun Doyle – stage-hand, prompt, general all round factotum – played by Angela Pezzano, who finds lots of fun and comedic moments in this role. She eyes the food she serves hungrily, then furtively steals a mouthful as she clears it way. She follows Leigh with childish awe after realising it was her she saw in Gone With the Wind.

Smooth and carefully choreographed set changes take the play from Dublin to London and to a room in Notley Abbey. Equally smooth lighting effects enhance the production.

Stojanovic pays effusive credit to the large creative team, and to the cast who achieved this insight into both “a play rich in theatre history” and “the remarkable lives and personal tragedies” portrayed in this very interesting production.

Carol Wimmer

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.