Moth

The great virtue of Moth is that it takes us into the world and the feelings of misfits, the rejected, the spurned, the picked-on and persecuted – and does not ask us to feel sorry for them.

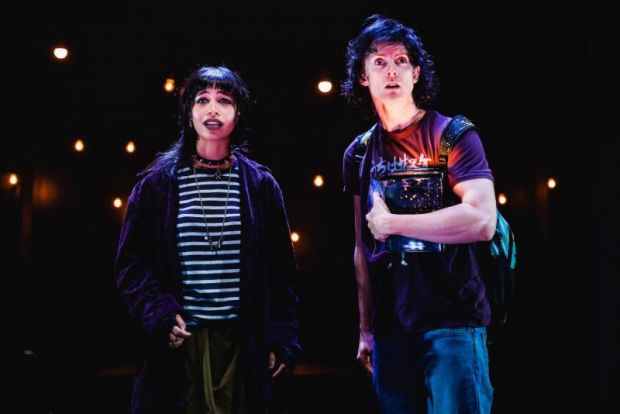

It shows us exactly, precisely why Declan Greene’s characters, schoolkids Claryssa (Lucy Ansell) and Sebastian (Adam Noviello), are teased and bullied. It’s scarifying. We might, if we are honest, uneasily feel that we too might avoid them in real life. They are too ‘different’, they are weird. They don’t conform and they are therefore threatening; they are an implicit criticism of the ‘normal’ and therefore inevitable targets for bullying and even destruction. It is atavistic to turn on the injured.

Claryssa, an emo Wiccan, is belligerent, rude, and confrontational. Sebastian, with his sad mother whom he can’t help, is lost in his world of anime, weird pop and sci-fi horror; he has an irritating laugh, and he literally smells. And yet Declan Greene makes us almost admire their courage in sticking to being who they are…

These contradictions are sharply, clearly realised in two splendid performances. Ansell gives us the rather underwritten Claryssa who is solid, stolid, aggressive and fearless, supposedly indifferent to being hated. (The playwright’s notes specify that Claryssa is ‘tall and overweight’; Ansell is neither. It doesn’t matter.) But it is Sebastian’s story and Noviello’s performance is quicksilver astonishing, using their body like a dancer, somehow suggesting a restless, nervy, skinny, nerdy, cowardly, smelly, maybe epileptic, appallingly lonely kid who virtually invites persecution and whose retreat into quasi-religious visions is entirely convincing. (The visions themselves may be another matter.)

But not only do Ansell and Noviello play Claryssa and Sebastian in the present, they must also ‘play’ other characters in their dangerous world – not transforming themselves into these characters but giving us their versions of these characters so that they remain Claryssa and Sebastian narrating their story. And there is no obvious logic to this: Claryssa can play school bully Clinton; Sebastian plays Mr Paglos their art teacher – or, teasing, Claryssa herself. In this fugue-like text, these jumps in and out of character and in and out of past and present are enormously demanding, but Ansell and Noviello never falter, and we always know where we are and who’s talking.

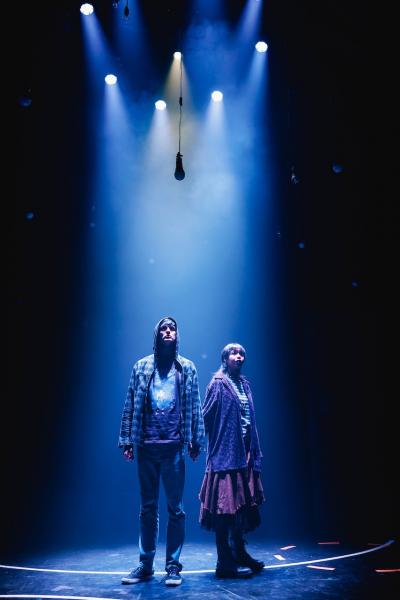

The strange, alien, near sealed world of Claryssa and Sebastian is enhanced by Niklas Pajanti’s intricate and brilliant lighting and the overall production design of Pajanti, Justin Gardam and director Briony Dunn. Dunn’s work here is clearly the result of close attention to detail, to every nuance of character and her actors’ expressive movements. There are no props. There are two flats and a platform up stage. That’s all – and the focus is unrelenting.

Are Sebastian and Claryssa friends? Only out of necessity. There is no trace of sexuality, let alone romance. They show affection by teasing and outright abuse. They are mates, drawn together by their defiant outsider-ness.

But it is a crucial, sickening scene of betrayal of this friendship, frighteningly lit by Pajanti, a no escape exposure, that sends Sebastian over the edge and into a space where he sees apocalyptic destruction, angels, swarms of moths, and one moth (the moth, that he calls ‘Sebastian’ ) in a glass jar and it is both a metaphor and a messenger from God, come to give this sad fuck-up kid a mission to save the world.

Noviello is so marvellous that they almost makes this work, but it rather leaves us behind because Sebastian is disappearing into crazy. We know why, but we can’t follow him there. We can see the intention, but it feels arbitrary, full of obscure detail and we might feel Declan Greene is pushing his luck – and pushing towards ‘relevance’ to the world of 2010 when the play was commissioned and first performed.

Moth was commissioned by Chris Kohn specifically as a play for teenagers and now, in 2023, the teenagers in the opening night audience clearly connected. Whether the references to anime monsters, St Sebastian and avenging angels, swarms of moths, a moth in a jar, horror pix and Jesus’ glowing heart all made sense is debateable, but there was the shaming recognition of these characters, of what happens to them and what could happen to them. Excursions into madness aside, by the end we are profoundly sobered and shaken at the fate of someone who doesn’t and won’t belong.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Daniel Rabin

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.