The Mill On The Floss

On a bare stage, eight actors, dressed simply in white, skirts for the women, grey jackets for the men, play fourteen clearly demarcated characters. With these apparently – but only apparently – simple means, director Tanya Gerstle brilliantly creates a contemporary interpretation of a much loved, classic 19th century novel. We are in Lincolnshire, we are back in the 19th century at a mill on the (fictitious) River Floss. A bright, curious, highly intelligent and adventurous nine-year-old, Maggie Tulliver (Maddie Nunn), reads voraciously, plays with her beloved older brother Tom (Grant Cartwright) by the river, cuddles with her Indulgent father (James O’Connell)… and faces what will be an uncertain future. In just over two hours we will see Maggie grow up, subject to all the restrictions, obstacles and assumptions of 1820s rural England – compounded by poverty. But this play is no reverent museum piece: time after time we are struck by how little fundamental attitudes have changed. True, if you don’t know the plot of the novel – or don’t read the very brief plot summary in the program - you may struggle just a little, but not for long. In the very first scene we learn that little Maggie reads about the drowning of witches. It frightens her on some deeper level – and sets up a motif of drowning that is repeated throughout the play. Maggie herself is no ‘witch’, but what was – or is – a ‘witch? An uppity woman, who doesn’t know her place, a mouthy bitch, questioning male authority and privilege.

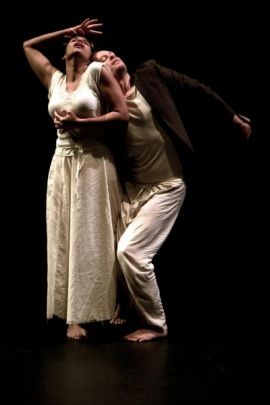

How does the immensely respected and experienced Tanya Gerstle bring all this to life? The bare stage employs no more than a raised platform, a number of straight back chairs, a table and a minimum of suggestive props – piles of books, autumn leaves, sheet music. Lucy Burkinshaw’s lighting is highly, dramatically expressive, illuminating then isolating, making sunshine and nightmares. Russell Goldsmith and Tom Backhaus’ subtle sound design supplies the rushing river and the rain, almost unnoticed until crucial to the action. But Ms Gerstle’s greatest resource is her cast. Those who play two roles rise to the task admirably. Louisa Hastings Edge transforms (with no change of costume) from the insouciant Mrs Tulliver to Maggie’s rich fun-seeker cousin Lucy. Grant Cartwright grows playful boy Tom Tulliver into a grim, chip-on-his-shoulder man – and, with a simple change of jacket and obscured by shadows, the flinty Mr Wakem. Tom Heath is sweet and moving as the sensitive, intelligent but deformed Philip Wakem (the novel’s hunchback becomes a twisted, clenched hand) – and, in another great transformation, the cheerful illiterate Bob Jakin. Zahra Newman, as the teenage Maggie, delivers a painful but touching contradiction: the warmth of her natural persona is boxed in by the self-abnegating, angry front she chooses to deal with her circumstances. Finally, Rosie Lockhart as adult Maggie is her splendid self, torn by her pride, and her sense of what is ethical posed flat against her desire. All the cast do not merely speak but sing and move – or dance, I should say – in highly expressive ways, suggesting torment, desire, violence and death. These things they do with skill and grace, conveying powerful emotions with music and movement.

How does the immensely respected and experienced Tanya Gerstle bring all this to life? The bare stage employs no more than a raised platform, a number of straight back chairs, a table and a minimum of suggestive props – piles of books, autumn leaves, sheet music. Lucy Burkinshaw’s lighting is highly, dramatically expressive, illuminating then isolating, making sunshine and nightmares. Russell Goldsmith and Tom Backhaus’ subtle sound design supplies the rushing river and the rain, almost unnoticed until crucial to the action. But Ms Gerstle’s greatest resource is her cast. Those who play two roles rise to the task admirably. Louisa Hastings Edge transforms (with no change of costume) from the insouciant Mrs Tulliver to Maggie’s rich fun-seeker cousin Lucy. Grant Cartwright grows playful boy Tom Tulliver into a grim, chip-on-his-shoulder man – and, with a simple change of jacket and obscured by shadows, the flinty Mr Wakem. Tom Heath is sweet and moving as the sensitive, intelligent but deformed Philip Wakem (the novel’s hunchback becomes a twisted, clenched hand) – and, in another great transformation, the cheerful illiterate Bob Jakin. Zahra Newman, as the teenage Maggie, delivers a painful but touching contradiction: the warmth of her natural persona is boxed in by the self-abnegating, angry front she chooses to deal with her circumstances. Finally, Rosie Lockhart as adult Maggie is her splendid self, torn by her pride, and her sense of what is ethical posed flat against her desire. All the cast do not merely speak but sing and move – or dance, I should say – in highly expressive ways, suggesting torment, desire, violence and death. These things they do with skill and grace, conveying powerful emotions with music and movement.

This adaptation isn’t the novel simply translated to a theatre stage. It is the interpretation and use the adaptor – and now Ms Gerstle and her cast - have made of the novel. What that interpretation achieves – and this production bodies forth – is a Maggie Tulliver (carrying within her the choices she’s made and all her shaping life experiences) blocked, frustrated – but again shaped – by a structure and an ideology against which she might struggle but cannot escape. Here we see three iterations of ‘Maggie’ Tulliver. We know this is what we’ll see from the program, which tells us ‘Maggie One – Maddie Nunn; Maggie Two – Zahra Newman; Maggie Three – Rosie Lockhart.’ What we don’t expect is that all three Maggies are, at crucial turning points, on stage together – a device that could fall over with a thud, were it not precisely choreographed and directed by Ms Gerstle – who seems to know exactly what she means to say - and manifested by these three women. Thus when Maggie Three – the supposedly grown woman – begins to fall in love with ‘the wrong man’, the charming Stephen Guest (George Lingard – just about perfect in this and his other role), the bold, curious child Maggie One urges her on while stern, judgemental Maggie Two admonishes her. Thus the internal struggle is made external and we lean forward, gripped by the performances and what is at stake to see which will win.

If the play gives less weight than it might to the trap of Maggie’s love for her feckless father, it strongly dramatises Tulliver’s ‘right’, as the patriarch, to persist with his foolish lawsuit against Mr Waken. That lawsuit, even within the conditions and mores of the time, sets in train the disasters that follow. Tulliver is unhindered by his wife; she absolves herself as a mere woman. His position is reinforced by the female relatives, Mrs Glegg (Zahra Newman doubling) and Mrs Pullet (Rosie Lockhart doubling), who, if they are sketchy, serve their purpose in this interpretation of the story. Tulliver’s stubborn recalcitrance separates Maggie from her first love, Philip, son of Tulliver’s adversary Wakem. It dooms Tom Tulliver to abandon a law career and to take instead a tedious clerical job. That in turn exacerbates Tom’s vengeful chauvinism toward Maggie. And Maggie herself, helpless, her hopes dashed, opts for self-denial and austerity.

If the play gives less weight than it might to the trap of Maggie’s love for her feckless father, it strongly dramatises Tulliver’s ‘right’, as the patriarch, to persist with his foolish lawsuit against Mr Waken. That lawsuit, even within the conditions and mores of the time, sets in train the disasters that follow. Tulliver is unhindered by his wife; she absolves herself as a mere woman. His position is reinforced by the female relatives, Mrs Glegg (Zahra Newman doubling) and Mrs Pullet (Rosie Lockhart doubling), who, if they are sketchy, serve their purpose in this interpretation of the story. Tulliver’s stubborn recalcitrance separates Maggie from her first love, Philip, son of Tulliver’s adversary Wakem. It dooms Tom Tulliver to abandon a law career and to take instead a tedious clerical job. That in turn exacerbates Tom’s vengeful chauvinism toward Maggie. And Maggie herself, helpless, her hopes dashed, opts for self-denial and austerity.

Some may object to the choices made by Ms Edmundson in her adaptation. But any adaptation (as opposed to a mere reduction to fit time restraints) involves choices. And those choices are dictated by the adaptor’s intentions. Why tell the story (or a version of it) of The Mill On The Floss? And why tell it now?

This isn’t a light and fluffy ‘entertainment’. It asks you to concentrate and enter into its supreme theatricality with your imagination. And then it engages the emotions and reveals a comprehension, indeed an apprehension, you may not quite have had before you saw this piece of theatre. Ms Gerstle has wrought a focussed, cohesive and pointed piece of storytelling, which is theatrical in the sense that it must be seen – and could only be seen – in a theatre. See it if you can.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Pia Johnson.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.