Milk & Blood

Milk and Blood are two quite separate but thematically linked monologues. Each has their characters – ‘Mummy’ in Milk, ‘Daddy’ in Blood – alone on stage for sixty to seventy minutes. No other characters, no props. Just empty space which, via movement as controlled as dance, and Harrie Hogan’s lighting becomes a home, a street, a garden, a prison… But as this stripped bare mode incites our imagination, we are also held by developing narrative threads; incidents are not incidental, and cause and effect builds and builds to a revelation – for the characters and for us.

In Milk, Bridget Gallacher is ‘Mummy’, a working-class woman who defines herself above all as a mother, a woman for whom the bond between mother and child is her raison d’être. Gallacher’s performance creates an intensely physical presence so that we are keenly aware of this woman’s body that makes babies. She’s cheerful too, always smiling. (She reminded me of Sally Hawkins’ character in Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky in which we begin to doubt the perpetual smile and suspect it might be a front to ward off despair.)

The palpable joy that Mummy shows talking about her first son, Boy, makes us joyful with her. But she does let slip – as if it’s unimportant - that she had Boy when she was seventeen and by then already had had an abortion. Beloved Boy, grown up now, a child no longer except to Mummy, is in gaol. She has a second son – Doug – a youngster. Doug’s a bit fractious, so things are not quite as idyllic as it was when Boy was a littlie. Fathers are never mentioned. Now Mummy is pregnant again and ecstatic – she just loves being pregnant! This time there’s boyfriend who moves in – and he’s all right too – but when he threatens Mummy’s version of reality, she throws him out…

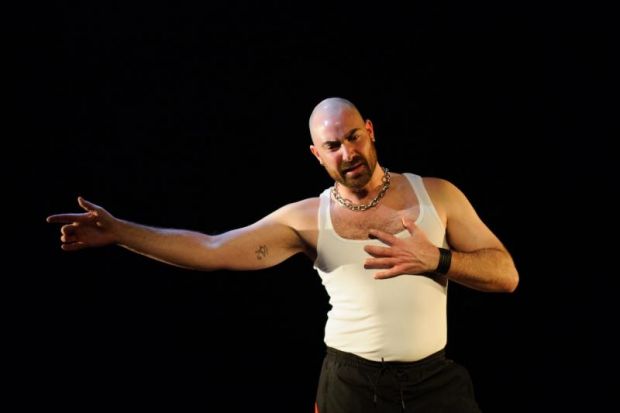

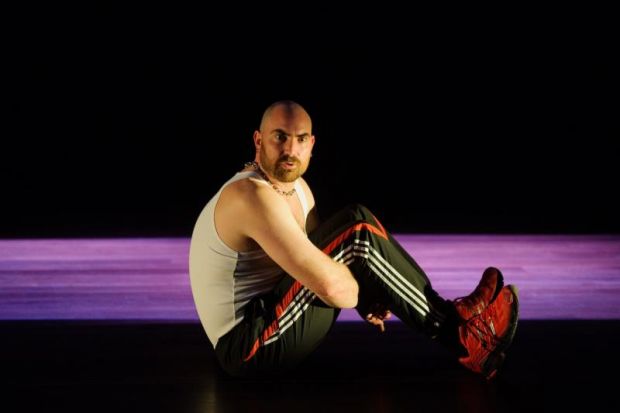

In Blood, Charles Purcell’s ‘Daddy’ is a sex worker who specialises in domination and BDSM, a caring, controlling and moral specialist – a father figure - for whom the pleasure of the ‘sub’ client is paramount; that is his raison d’être. When he speaks of his sexual interactions with his gay clients, he makes the experience sound transcendent, as if he is taking them to another realm – even while maintaining total control of himself. He teaches his techniques and spiritual systems to other aspiring ‘doms’. He has an acolyte, ‘Pup’, living with him temporarily. But Daddy maintains the Daddy role and sometimes Pup disappoints by not living up to Daddy’s ethical standards – and suffering for it. Purcell’s performance too is intensely physical: a muscular figure who works out religiously, he is imposing, he radiates power – and yet there is a hint of his determined control shading into a rigidity or the mechanical, a carapace that sadly inhibits his being whole.

Both characters, despite the enormous differences of personality, lifestyle and intelligence between them, maintain beliefs about themselves and the reality of their world – until a devastating crisis shatters those beliefs and sets Mummy and Daddy free.

As playwright Benjamin Nichol has said in a radio interview, the monologue form can take us deeper into the thoughts and feelings of the characters as they confide – or confess. Of course, those thoughts and feeling are not unfiltered: they are shaped and selected so as to maintain these characters personas – their sense of themselves and their world. As each monologue proceeds, we begin to sense more than we are being told – and that creates a certain distance and a gripping dramatic tension. It’s a tension that somehow precludes sympathy even as we observe these characters and gain a deep and moving understanding of them.

These plays are not easy; they are impressive because of their narrative structure, the choice of detail, the thought, insight and emotion that has gone into them, and the very high quality of the performances.

For the record: Milk and Blood were developed together by an exceptionally cohesive team. While Benjamin Nichol directed both plays, Gallacher co-directed Milk and was dramaturg on Blood. Purcell co-directed Blood and was dramaturg on Milk. Izabella Yena provided additional dramaturgy while lighting designer Harrie Hogan and sound designer Connor Ross were an intimate part of the development process from the start. This is not ‘group devised’, it is true collaboration, and it has certainly paid off here. Both texts are tight and show a sure-footed awareness of theatre and audience response.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Sarah Walker

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.