The Meeting

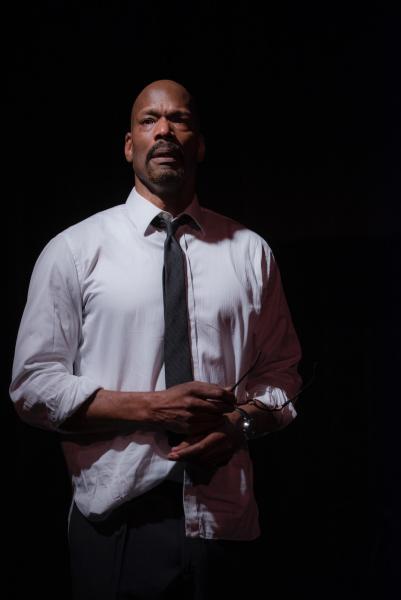

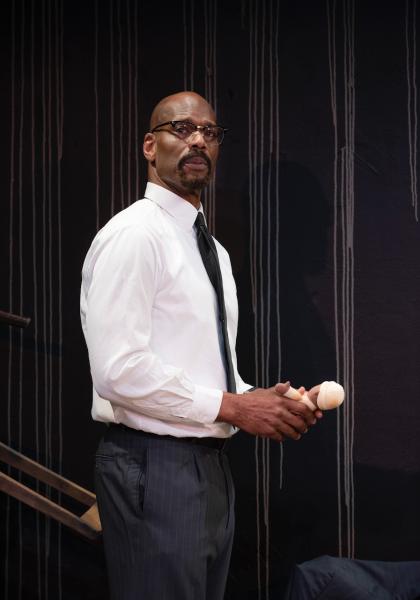

In a bare room, high above Harlem, a stack of chairs in the corner, Malcolm X (Christopher Kirby) sleeps on a wooden table. He’s woken by a nightmare. Why not? He’s under continuous FBI surveillance and his former religious organisation, then Nation of Islam, is now his implacable enemy. His bodyguard, Rashad (Akhilesh Jain), jumpy and suspicious to the point of paranoia, questions the imminent visit of Dr Martin Luther King (Dushan Philips)…

In reality, Martin Luther King and Malcolm X did meet only once and for a bare couple of minutes in March 1964 when they both attended the US Senate debates on the Civil Rights Act. Who knows what they may have said to each other that day, if anything, when Malcolm X had referred publicly to King as a ‘chump’ and a ‘[white] stooge’?

The Meeting imagines what would or could have happened if they had met, in secret, alone, face to face, for longer, at Malcolm X’s invitation, in February 1965. It’s just a week before Malcolm X’s assassination. He doesn’t know he’ll be dead in a week (and nor do we unless we read the program notes) – although he had predicted that the Nation of Islam, of which he has been a leader until the early 60s, was actively trying to kill him. Whether they did or not is still not entirely clear.

Once Malcolm is awake and prowling the room, the energy, the humour, the menace, and Christopher Kirby’s own charisma fill not just the stage but the theatre itself. When King arrives and scowling Rashad has insisted on searching him, we get a striking contrast in styles, not just in ideologies. Dushan Philips, a shorter more compact man than the rangy, towering Kirby, gives us Luther King’s quiet but intense dignity even while suggesting the conscious effort that takes. It’s never explicitly, specifically clear why Malcolm has invited King to this meeting, nor why King has come, but by the play’s end it is clear – a mix of curiosity, need and, despite everything, a shared aim.

But immensely experienced playwright Jeff Stetson does not give us a history lesson (or ‘homework’ as a US movie producer once described it to me). In this 1987 play, he keeps the focus on the contrasting personalities of these two Black leaders, with just enough context for us to understand where they’re coming from. For instance, we learn that Malcolm’s house has just been burned to the ground and that he fears for his wife and daughters, an event that provides the pretext for one of the play’s most moving moments. King asserts the courage of non-violence, insisting that not acting is action.

These very articulate men, both orators, are driven by rage at racism and injustice. Where they differ is in what to do about it. King maintains the devout Christianity of ‘love thy neighbour’ while Malcolm, a convert to Sunni Islam by this, insists on Black people’s right to defend themselves and if that means violence, so be it.

The antagonism, the baiting, and thus the tension is palpable. At some moments, the action can feel a touch over-directed. Tanya Gerstle’s otherwise excellent direction pushes things into an excessive physicality to demonstrate the aggressive competition for dominance between the two. Throwing chairs around? A tug o’ war? And we’re not sure whether this is metaphor or real. Nevertheless, we see the two men finally connect – as fathers if nothing else. But Malcolm’s last line, after King has left, has a sting in its ambiguity.

If Malcolm’s ideas and methods seem crazy, and even futile, you understand what drives them and you understand why he inspired love and pride in Afro-Americans – and fear in white folks - and why he rejected Luther King’s non-violence and assimilation. But you also are again left admiring Luther King’s courage, restraint, and patience.

But why revive (if that’s the word) this 1987 play featuring a debate between these two assassinated leaders? Because, as Gerstle says in her program note, the context still sadly exists. As I listened to these superb actors argue on stage, I couldn’t help thinking of the murder in plain sight of George Floyd, or the murder of Daniel Prude in Rochester, NY, or the precise articulation by James Baldwin of ‘the White problem’. And afterwards, you might think of the revisionist histories now emerging of colonisation and Empire.

The Meeting is sustained by two sustained, powerful performances (and not forgetting Akhilesh Jain either) and the sharp ebb and flow of sympathy for the ideas so forcefully put.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Jodie Hutchinson

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.