Lucia di Lammermoor

Lucia di Lammermoor is one of the staples of most large opera companies. It contains some of Gaetano Donizetti’s most famous music, including of course the famous mad scene, immortalised by Sarah Coburn, Lily Pons, Maria Callas, Nellie Melba and the legendary Joan Sutherland among others!

From a novel titled The Bride of Lammermoor by Scottish novelist, poet and playwright Sir Walter Scott, originally in English, the novel and the opera share the same setting and storyline. The main difference between both works is that of the character names. Italian librettist Salvatore Cammarano changed the novels’ anglicised names to Italian versions for the opera, meaning Lucy became Lucia and Edgar, Edgardo.

The heroine of the novel, Lucy, is based on Janet Dalrymple, the daughter of the 1st Viscount of Stair who secretly got engaged to a political enemy of her family. Just like Lucy in the novel, Janet was forced to marry a different suitor and overcome with stress, subsequently stabbed him on her wedding night.

Lucia di Lammermoor tells the tragic tale of Lucia, a woman who is constantly manipulated by the men in her life. When she becomes involved in a family feud by falling in love with their sworn enemy, Lucia is pushed to her limit and finally decides to take control of her situation, with tragic consequences for the life of her new husband and her sanity.

It is a story that has resonated through the centuries and is still relevant today, hence the Metropolitan Opera’s decision to select Australian theatre and film director Simon Stone to bring the opera into the new century both in its setting and its presentation.

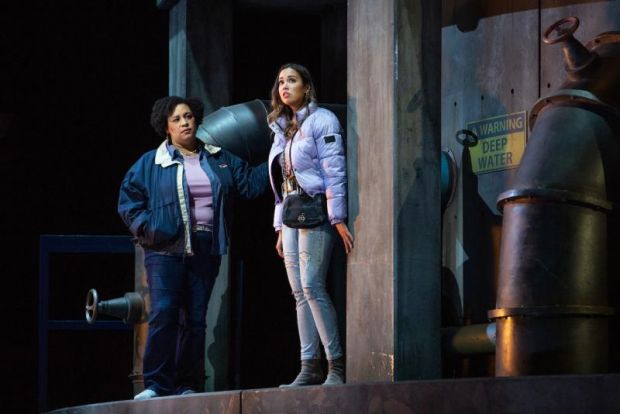

Stone, together with set design by Lizzie Clachan, with lighting by James Farncombe, choreography by Sara Erde and costumes by Alice Babidge and Blanca Anon, have created a gritty real world set in the American Rust Belt with a pawnshop, a cheap motel, a liquor store, and an ATM that charges too much.

The set is mounted on a giant revolve that is endlessly turning to give new acting areas and features a large video screen mounted at the top which gives us glimpses into Lucia’s thoughts and dreams.

While both the set and video screen are clever devices, one wonders if they are really ‘fill ins’ to cover the long arias which would otherwise require the ‘stand and deliver’ approach.

At times I found the videos distracting, over-elaborating what the music was already saying far more eloquently.

Maestro Riccardo Frizza’s orchestra is the glue that holds the production together. Not only do they produce an exquisite sound, but thanks to Frizza’s baton, they perfectly support the singers and add a richness to the whole opera.

The cast are uniformly strong, headed by the incredible Sierra Nadine in the title role. In an effortless yet impassioned performance she makes the role her own, fragile yet volatile. Her mad scene (an aria lasting some 20 minutes) is riveting from start to finish. Special mention should be made of the glass harmonica solo by Friedrich Heinrich Kern.

Artur Rucinski’s Enrico is domineering, loyal and misguided, all skilfully portrayed in one person. His “Cruda, funesta smania” is expertly managed.

Javier Camarena’s Edgardo is loyal, passionate and focussed on what he wants. His aria from Act III, “Tu Che A Dio Spiegasti L’ali” (while hurrying to the town, hearing the death bell ring and thinking Lucia is dead, He kills himself to be united with Lucia in death), is moving to the extreme.

Deborah Nansteel’s Alisa, Lucia’s friend and confidant, features a strong velvety warm voice that perfectly blends with that of Nadine, particularly in the duet “Regnava nel silenzio”. It is a tender moment of friendship and devotion.

Christian Van Horn was called in late to play the role of Raimondo but did not disappoint, with a powerful bass voice, particularly in “Dalle stanze, ove Lucia”.

The Met Opera chorus rounds off the cast playing multiple characters that inhabit Lucia’s world.

While this production of Lucia di Lammermoor may be ground-breaking in that in it presents the opera in a contemporary setting using modern technology, this same technology tends to overexplain the text of the opera at times leaving little to the imagination.

While Lucia di Lammermoor is earthy and ‘in your face’ visually (which is not a dreadful thing), it is glorious musically and a tribute to Donizetti’s score!

Barry Hill

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.