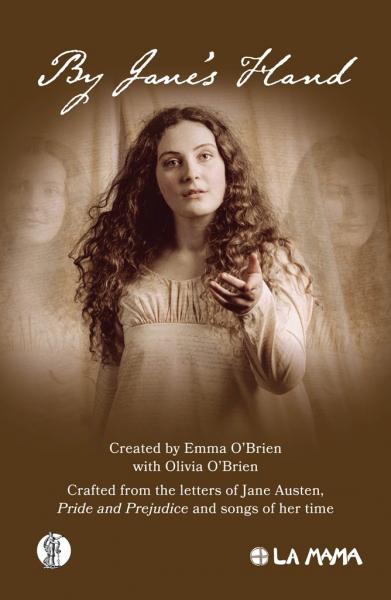

By Jane’s Hand

Emma O’Brien and Olivia O’Brien combine, weave together, and segue between ‘fact’ (or what Jane Austen made of it in letters to her sister Cassandra) and fiction. ‘Fiction’ being how Jane Austen turned life – what she observed and what she felt - into art. Specifically here, the much-adapted Pride and Prejudice. There is not a word in the O’Briens’ text that does not come from Jane’s hand. And that text weaves into and out of the music of her time that Jane Austen transcribed - from children’s ditties to classical arias.

And if that mix were not rich enough, ‘Jane’ is played by three women (Olivia O’Brien, Isha Menon and Marjorie Hannah) as Jane One, Jane Two and Jane Three – who also play musical instruments and sing – beautifully - much of the text. The writers decided that just one ‘Jane’ was not enough to portray this multi-facetted woman. In the play, the three Janes may speak or sing in unison, or singly, alone or in counterpoint. If we could distinguish among them, Jane One (pianoforte) is rather pre-Raphaelite and dreamy – but also the source of the acerbic letters, Jane Two (harp) cheeky and knowing, and Jane Three (violin) ‘serious’ and realistic. But the portrayals are more fluid than that.

In Act II (there are three acts in the show’s compact fifty-five minutes), they also play key characters from Pride and Prejudice: sparky but prejudiced Elizabeth Bennett, the loathsome Mr Collins, imperious Darcy and haughty snob Lady Catherine de Bourgh – with a flourishing of wigs and a top hat. (One’s enjoyment is certainly enhanced by knowledge of the novel – but after so many adaptations, ignorance of the plot is unlikely – but not fatal.)

All this is not in the least confusing. So skilful is the seamless interweaving of the text and of its performance, that By Jane’s Hand is delightful and insightful. It is all so well done that it disguises quite how well done it is, and it is only later that we realise with what consummate precision the whole thing has been given to us.

Clearly, much careful thought has also been given to the look of the thing. The set, designed by Emma O’Brien and Henry O’Brien, is littered with crumpled sheets of handwritten letters. The fabric of Susan Halls’ Empire line costumes is covered with more handwriting – as is Jane One’s piano, Jane Two’s harp and Jane’s Three’s dresser, where her violine rests when not in use…

The program notes tell us that ‘This play is not meant to be a revelation about [Jane Austen] or a new truth, but rather an immersion in multiple elements of the enigma of Jane Austen.’ Why an ‘enigma’? Because, apparently, Jane Austen wrote 3,000 [?] letters and only 161 survive. Why did her family burn the others? Of course, to ‘protect’ her. From what we hear in the show, the letters to her sister display sharp, sarcastic – indeed, to use some sexist terms, ‘bitchy’ or ‘catty’ - observations of people– even if they are almost certainly accurate – and rather close to Emma’s cruel attitude to Miss Bates in Emma. What By Jane’s Hand suggests is that Austen turned her observations on character into irony and implied moral judgement – with an undercurrent of pragmatic – if not cynical - realism. Her world is a man’s world. Let’s not forget that Elizabeth Bennett does begin to consider Darcy more favourably after she has seen Pemberley! As Fay Weldon wrote about Jane Austen: ‘She is not a gentle writer. Do not be misled; she is not ignorant, merely discreet; not innocent, merely graceful.’

What the play also suggests in its contrast of Austen’s letters and her fiction is that she transformed her somewhat constrained personal experience (not all ‘hearth and home’) – and including thwarted romance - into Romance, the quality for which some folks claim that they read and re-read the novels. But Darcy is won over by someone rather like Jane – or perhaps Jane as she would’ve liked to have been. Emma finally realises the Mr Knightly is The One; and in Persuasion lost love is regained. This observation is hardly new, but By Jane’s Hand, with it’s clever, measured juxtapositions, throws it into sharp relief.

This ‘little’ chamber piece, so witty and skilful, and performed with such delicacy and gusto, is a must for Austen fans in revealing there was and is much more to her than ‘everybody’s dear Jane’.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Darren Gill

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.