An Inspector Calls

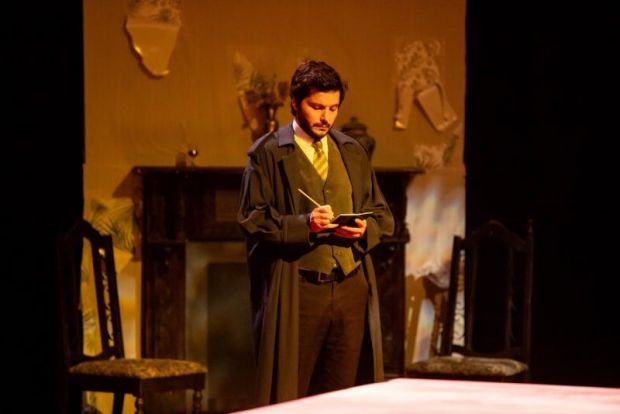

A well-to-do family gathers after dinner: there are toasts from the father, and the daughter’s suitor presents her with an engagement ring, whilst the son sulks in the corner. The women have just retired to the drawing room, when there is the sound of a doorbell and a servant walks into to announce an Inspector has called.

It’s a classic play from writer J. B. Priestley, starting with an apparently perfect family, then the report of a death, and the questioning of an inspector, cracks open their secrets, one by one. Its themes are morality and community responsibility, and whilst written at the end of the Second World War, but originally set just before the First World War, its message of being accountable for the consequences of your actions is no less relevant today – it still exposes and criticises the hypocrisies of society, regardless of the year.

Indeed, director Andrew Hawkins has extended Priestley’s approach that considers past, present, and future, by setting each of the three acts in a different time period. British director Stephen Daldry adopted a similar approach in the UK’s National Theatre 1990s revival, though he only referenced the era of its writing and its original setting. Hawkins extends that, with the third being the Covid crisis of 2020. It’s the same family, with the same choices, so is told linearly as originally written. It works well, the actors maintaining the personalities of their characters, just updating their clothes.

All the performers are excellent: standouts are Charis Button, as the daughter, Sheila, who has a huge emotional range to work through, which she makes look easy; Rodney Hrvatin and Janet Fletcher as the father and mother are suitably smug – then indignant at being accused of being caught up in this. Their main concerns of how the tragedy affects their class standing makes them unlikeable, yet Hrvatin and Fletcher ensure they are always relatable. Paul Pacillo is superb as the Inspector. Incisive, resolute, and almost always calm, landing his dialogue at the perfect moment for maximum effect. And when Pacillo is loud, it’s so opposite to his usual demeanour that the audience is as shocked as the Birling family.

The women who play the victim, Eva Smith, are outstanding – a different performer for each period. They say so much without saying anything; their performances are silent, the story carried in the expressions on their faces. The utter contempt from Trinity Witzmann in 1912; the happiness then despair of Genevieve Hudson in 1940; and Olivia Bennett showing the complexities of being afraid but trying not to show it in 2020. These three are haunting on the stage, moving around the rest of the cast as ghosts, or depicting silent-movie versions of their pasts.

This production is superbly directed by Hawkins. Working his actors in the round is challenging when they’re always going to have your back to someone, but this is done with the minimal inconvenience – they move, but always with purpose. The scenes are well-paced – the unravelling of the story builds tension carefully, simmers just long enough, then its necessary release is a slow-dawning more than an explosive reveal. The lighting is a star too: with such a large space in the round, the actors remain well-lit wherever they pause, or shadowed outside a window looking in. The blackouts are used to great effect too.

Sound is mostly dialogue, but there is genius in its minimalism: having an earlier sound effect of the front door closing off-stage sets up the audience to the act 2 climax when we hear it again – and every head turns to the door to see who it is.

Props are similarly nominal – mostly glasses of champagne or port – and the set is simply decorated with a handful of chairs, and a huge dining table, that also serves as the factory, a hospital bed, a mortuary slab – just from the actions of the performers. Costumes from Susan Harvey and director Hawkins serve to remind us of which period we’re in – the story is told by the performers.

This all combines beautifully to tell the stories of the victim, Eva Smith, and show us the circles of emotion of the family. Its call for collective accountability is even more relevant today, and you can’t help but come away from this performance feeling like you must do something about it. Much of the Fringe is about instant gratification, and away from that escapist comedy and cabaret of the massive Fringe hubs, this is a wonderful evening out that entertains, considers, and challenges.

Review by Mark Wickett

Production photography by Mason Digital

To check out our round-up of Adelaide Fringe reviews, click here.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.