Hercules

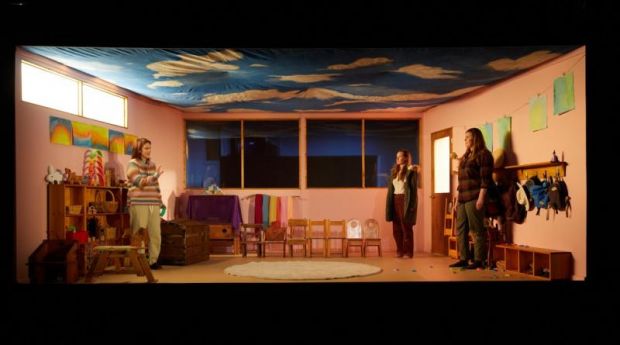

We take our seats in the cavernous Arts House space and we have plenty of time to check out Romanie Harper’s and Bethany J Fellows’s brightly lit set before the show begins. It’s a spacious kindergarten, stocked with toys, blocks, little chairs and a dress-up box. Colourful cushions. Lots of kids’ art on the walls. There are big windows up stage. Then: blackout.

Lights fade up. The room is dimly lit via light through a single door into… a corridor? A silhouetted figure (Mary-Helen Sassman) is discovered, seated downstage left, clutching a little chair, but maybe sleeping, maybe hiding. Another woman (Katherine Tonkin) enters. Silence. Time stands still. Woman #2 finds Woman #1 and tries to take the chair from her. Woman #1resists. Woman #2 proceeds instead to line up little chairs in a row.

I already know that Hercules is a group-devised show; that’s what the prestigious, award-winning Daniel Schlusser Ensemble does. In a program note, Schlusser and the Ensemble tell us they believe in ‘the value of ensemble-created theatre as both an ethical and artistic position.’ As I try to comprehend what I’m seeing, I also think, okay, this play is going to be allegorical, metaphorical, allusive, enigmatic, difficult, maybe impenetrable - and possibly self-indulgent. And so it proves.

There is no pay-off to the line of little chairs, but eventually there is more light, and soon a third woman (Edwina Wren) enters. The performances of all three women are contained, necessarily self-absorbed but creating three distinct personas. A flickering, rolling image on a television screen, and huge roman numerals are projected outside those big windows up stage. Each number seems to reflect a change of story, or subject, or mood.

The three women engage in bursts of conversation, each burst making sense per se, with references to literature, pop culture and class - but with no apparent connection to what has gone before or what follows. There are some repetitions that are pointed and witty. There are bursts of hostility and aggression. But it is as if the text and the performers are ticking off ‘points’… and then moving on to the next.

The press release for the show cites as subjects or issues, ‘the pressures of hyper productivity, particularly on mothers and carers; culturally codified misogyny; and the tragic consequences of confused masculinity, heroism and coercive control.’ High aims, but on stage these actually hard-to-detect references to such issues don’t cohere into a whole. The dress-up box is opened – and overturned. An arm comes through the wall (à la Repulsion). Coloured blocks are arranged – then scattered. Slogans are written on art paper and stuck to the walls. Pieces of shit are found – then hidden. Every now and then, there is the sound of an explosion and a flash of dangerous light as if the women are in a war zone. A war zone is a masculine thing, but otherwise, connection to or analysis of Hercules or ‘heroism’ eludes me.

In all this, Amelia Lever-Davidson’s lighting design and James Paul’s sound, music and – especially – his AV work are simply superb. They must know what’s going on. As the show proceeds, their work, and that of designers Harper and Fellows, becomes more and more ambitious and enthralling. An underworld from which fire and wind and some creeping creature can emerge is revealed. We finally hear the horrible story of Hercules’ other deeds beside the famous twelve. And such is the power of this hidden, now vividly told story that there must be prehistoric, razor teeth monsters and an all-engulfing horror that swallows all.

The connection between myth and behaviour is crucial, but whether Hercules succeeds in bringing into question a toxic version of ‘heroism’ and its grip on contemporary culture is another matter, but the ending is a powerful, frightening climax to this otherwise rather opaque and alienating show.

In a Q&A interview included in the program, Schlusser talks about the inspiration for the play, principally Euripides’ never performed The Madness of Hercules – as opposed to Euripides’ female violence play, Medea. The Ensemble’s aims and intentions are important, intriguing, and complex. The idea of exploring masculinity with three women performers is an excellent one – although such a thing has been done before even if at a far less ambitious artistic level. Schlusser says the Ensemble’s theatre is ‘a place for audiences to get connected to very deep feelings’. My problem is that these intentions do not seem to be realised in Hercules, that is, in the show we see. Although, I must say, on the way out, while a lot of people were muttering and saying, Hmmm’, we did overhear a young woman say, ‘My God, I’m exhausted… But in a good way.’ Perhaps she got it; she connected.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: Pier Carthew.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.