Everyman & His Dog

This is the story of a man who is given a dog. That is to say, a somewhat curmudgeonly man who has a dog foisted upon him. For his own good, of course. He has never liked dogs, due in part to certain stinking childhood experiences. He can’t accept ‘owning’ a living creature, and so he can’t bring himself to name it. He calls it ‘Dog’.

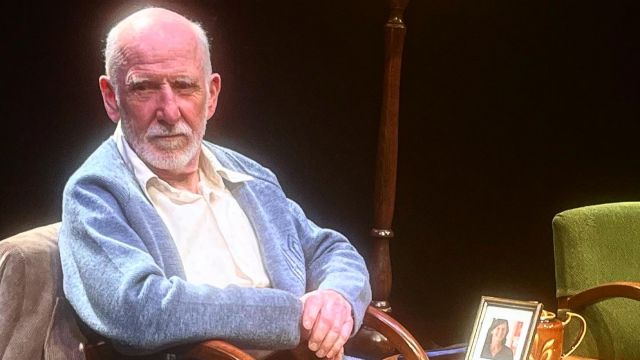

Dr John Everyman (Dennis Coad) is a retired doctor – a GP we gather. Now he ponders the oath he took at twenty-four, when he was starting out: ‘First, do no harm.’ Do no harm? He snags on this. He’ll come back to it. Of course, we do harm, all of us – intentionally or unintentionally. So, he wonders about his life…

Everyman & His Dog is a monologue that is a biographical story, a frank confession, a rant (against God), and a philosophical speculation. There are things in the story that Everyman still doesn’t understand – being old doesn’t necessarily mean wisdom. For instance, he is puzzled – if not embarrassed – when he meets his former patients in the street, and they clearly care about him and want to tell him about their lives.

On a stage decorated only by a couple of armchairs, an occasional table, a standard lamp, and a dog – the dog, a (mostly) prone Golden Retriever - he confides in us. As is the way with such presentations, about the highs and lows of his life. How he met, wanted, admired, and married his beloved Sofia – and how he lost her. That’s his main beef with God, a clearly spiteful, malicious Being – and that’s despite Everyman being an atheist. (I was reminded of Stephen Fry – another atheist – being interviewed by an archbishop on what he would say to God if it turned out there was a God…)

And then, without Sofia, Everyman is alone. He’s not specific about it, but Dennis Coad makes us feel his Everyman rattling around a big, empty, silent house. The sadness, the loneliness, exacerbated by a certain bitterness, is palpable.

Then, one day, unexpectedly, his grown-up daughter shows up with a dog. She’s always wanted a dog. He’s always not wanted a dog. Now he’s stuck with this dog: walking it, walking around it, feeding it, worst of all, picking up its shit – and all without his having the slightest relationship to this creature… this Dog.

His story is not dramatic, not sensational, rather ordinary in fact, but it is compelling; we hang on every word. Denny Lawrence’s direction is invisible, but clearly detailed and nuanced. Dennis Coad’s telling makes what seems such a modest claim on our attention: it is quiet, direct, sincere, and honest. Much of it is quite matter of fact, but there are flashes of anger and moments of humour, mostly in the jokes against himself. We recognise John Everyman, we feel we know him, and we think about our own lives or the lives of our parents, maybe rattling around in silent, empty houses.

And it is compelling because the writing – no frills, no rhetorical tricks, but elegant, spare, and direct – comes from a playwright who has been writing for forty years, play after award-winning play, all of them different, all of them with something to say about life, ethics, our foibles and failures, and always attuned to the now.

Here, yes, it must be said, we know where the story is going – but unlike some monologues it is going somewhere – and we are held by how we’ll get there. Suffice to say, how we get there is not at all predictable. Everyman is, perhaps, a departure for Elisha in being such a direct monologue. Deprived of the indirect back and forth dialogue between characters, this is a little slow to start as Everyman chews on ‘Do no harm’ longer than it needs. But then it takes off and it is the specifics that fire our imaginations and engage us. Recognition and emotion are audible among the audience. The Dog, sensing distress, lumbers to his feet, wags his tail and nudges John Everyman. ‘What’s up? I’m here.’

Michael Brindley

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.