Courage to Kill

A psychodrama about a Father (Stephen House) and his Son (Luke Mulquiney) locked in a hostile, poisonous but suffocatingly symbiotic conflict. It’s a conflict the Son sought to avoid – although it is with him and within him ever. His Father, recently widowed, has come to visit the Son’s cramped little apartment, and, if he can persuade the Son, he’ll stay - permanently. Father and Son. It’s natural. It’s right. It’s the last thing the Son wants. The Father, crusty, shabby, a retired waiter with a gimpy leg, is lonely, needy, sexually frustrated and given to bursts of wheedling confession and excuses - and accusations that his Son is a coward. The Son, also a waiter, claims to have no memory of his childhood, claims to despise his Father, and has erected a protective force field of indifference and self-absorption. Either one could leave, but they won’t – or they can’t. In a perverse way, they need each other. Their past locks them inexorably in a Dance of Death. From the start we know this will end badly; the question is how.

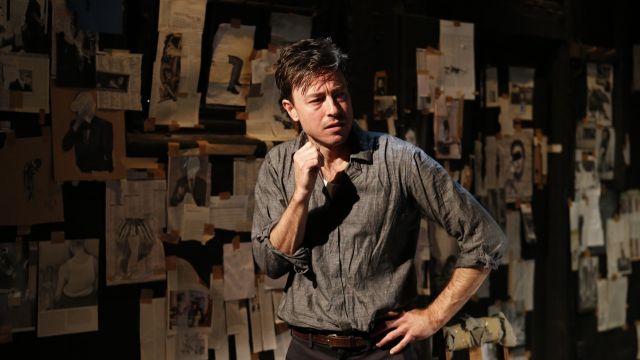

With this set-up, which takes all of the first act’s rather wearying hour, we expect something to happen sooner than it does. There’s an inescapable sense, at least in this production, of the characters circling and circling around the same nexus, of the wheels spinning, so to speak. The Son appears to have some sort of project in which he clips hundreds of articles and pictures from newspapers and magazines and tapes them to the walls. What’s this about? It looks like a set-up, but neither Father nor Son refers to it and nothing comes of it. At the interval, a friend asked what I thought of it. I had to say, I’d have to wait and see how it turned out…

A catalyst arrives in Act II. Radka (Tamara Natt), the Son’s live-in lover – although the arrangement is ambiguous – returns from the club where she performs. The presence of a third person immediately ups the tension. You almost feel you could do without Act I and that the play starts here. The Father, now in a dress shirt, plays waiter and serves dinner with wine. It could be a competition, but the Son refuses to engage. Instead he makes a harrowing confession of his cowardice – then leaves. In his absence, Radka flirts and parades her enticing body to the Father, quite aware of and enjoying her sexual power. Whether it’s credible that she allows things to proceed further than she expected is another matter… And is, indeed, the question of whether she ultimately affects the dynamic between Father and Son.

Lars Noren is a renowned and much awarded playwright, admired by Ingmar Bergman and apparently the most significant Swedish playwright since Strindberg. There is certainly a Strindbergian feel to Courage to Kill - as well perhaps as a touch of Pinter. But both these playwrights seem to me rather more economic than Mr Noren. Yes, he is allusive and there are metaphoric layers to the situation, such as both Father and Son being waiters. In Europe a waiter is, in fact, a respected profession and the text (if not this production) seems to intend to contrast that smooth surface respectability with the squalor of these men’s lives.

Lars Noren is a renowned and much awarded playwright, admired by Ingmar Bergman and apparently the most significant Swedish playwright since Strindberg. There is certainly a Strindbergian feel to Courage to Kill - as well perhaps as a touch of Pinter. But both these playwrights seem to me rather more economic than Mr Noren. Yes, he is allusive and there are metaphoric layers to the situation, such as both Father and Son being waiters. In Europe a waiter is, in fact, a respected profession and the text (if not this production) seems to intend to contrast that smooth surface respectability with the squalor of these men’s lives.

Radka, meanwhile, is part of a troupe that mimes popular songs, suggesting that she does not have – or cannot or dare not sing in – her own voice. As Radka, Ms Natt is a character playing a character, so to speak. Immediately sensing the tension, she is consciously fake – distant, bemused, ‘gracious’ - but also wary and anxious just underneath. Ms Natt succeeds very well as a brief femme fatale and catalyst. And when the Father tells her, ‘You’re so beautiful’, there is no need to suspend disbelief.

At the risk of seeming insensitive and disrespectful, I’d suggest that what this production needs is less of everything. To begin with, less text: an edit down to a tight seventy minutes with no interval would demonstrate the maxim ‘less is more’.

Less ‘acting’. Mr House and Mr Mulquiney, both experienced players, paradoxically agonise relentlessly, but bury nuance in aggressive naturalism with too little light and shade. For me, this suggests the actors’ attempt to overcome the play’s lack of development and the occasionally stilted nature of the translation – or they are at odds with the playwright’s actual intention.

Less sound design: the intention of Adam Casey’s sound design is clear, but it’s also excessive and overpowering - at odds with the text and by pushing heated melodrama (and the play is not melodrama) suggests Mr Casey and director Richard Murphet don’t really trust the play to be as ‘dramatic’ as it purports to be. Kris Chainey’s lighting is imaginative, taking down the fill and highlighting the combatants when important backstory is introduced, but it appears to violate its own apparent pattern and becomes too noticeable.

Less sound design: the intention of Adam Casey’s sound design is clear, but it’s also excessive and overpowering - at odds with the text and by pushing heated melodrama (and the play is not melodrama) suggests Mr Casey and director Richard Murphet don’t really trust the play to be as ‘dramatic’ as it purports to be. Kris Chainey’s lighting is imaginative, taking down the fill and highlighting the combatants when important backstory is introduced, but it appears to violate its own apparent pattern and becomes too noticeable.

After Mr Murphet’s terrific, witty and fast-paced Quick Death/Slow Love at La Mama last year, Courage to Kill is disappointing. But ‘Nordic noir’, as it’s called, is currently in vogue – in theatre as well as on television. With the latter, it’s the dark underbelly of the sunny welfare state, verging at times on the Grand Guignol. In theatre, it seems to be the intimate forensic examination of dysfunctional relationships. Earlier this year, for instance, we had Norwegian Jon Fosse’s Night Sings Its Songs at La Mama - also for me another bemusing experience in the light of the claims made for it and its author. I’d question whether these plays are in fact ‘naturalistic’ or whether they are stylised rituals. Perhaps the questions are: does the Nordic style really translate and what is lost in the translation?

Michael Brindley

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.