Complete Works: Table Top Shakespeare - Much Ado About Nothing / The Two Gentlemen of Verona / Romeo & Juliet

It’s an extraordinary undertaking to present every single play from William Shakespeare as part of an Arts Festival. No less challenging to do so with the only living performer being the narrator, whilst all characters are played by bottles of olive oil, cans of fizzy drink, or a pocket torch.

The UK theatre company, Forced Entertainment, has brought six actors to Adelaide for this massive adaptation of the famous and not so well-known tales – yet they are not there to act out the plays on a stage. Instead, one of them sits at a wooden table and narrates a play, and in modern English: there’s no Shakespearean language here, it’s all plain and simple to understand. This works particularly well for those who say they don’t like Shakespeare, because typically it’s the language that’s the barrier, rather than the stories themselves, which are often universal tales of love gained and lost, betrayals, misunderstandings and redemption (successful or otherwise).

Yet if you are a fan of the Bard, it can sometimes feel over-simplified, and the loss of Shakespeare rhythm is certainly felt – however, through the interpretation, you may discover new meanings that you hadn’t previously considered. And as a fan, there’s plenty to laugh at that others might miss, such as when you know a scene that has two characters talking over several pages and it’s calmly summarised by the narrator as ‘They talked for a bit. And they disagreed.’

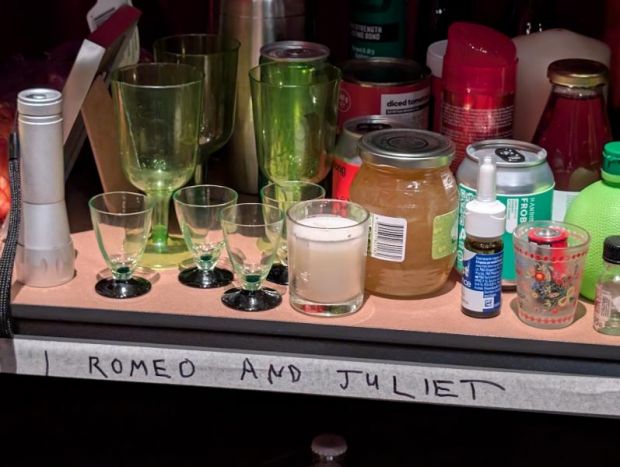

Focusing on the narrative doesn’t mean there are no other elements to the performance: the play is acted out using things found in a kitchen cupboard: tins, bottles, jars, candles, flasks – the use of household objects as the key players is a master stroke. It’s like we’re watching the director block the play, or even more simply, a child creating a story from nothing other than what is to hand in the kitchen.

In addition, it potentially overcomes another reason that some avoid Shakespeare – the large number of players with unfamiliar names. Assigning a tall, pointy ‘Liquid Nails’ glue gun as Lord Capulet, and the servants as diminutive shot glasses ensures you know what they are, even if you forget the names minutes later.

The combination of narrative and objects is expertly delivered – each time the character is named, the narrator reaches out to reposition the object that represents that character, a little prompt to remind you of who’s who. And it’s effective to turn the label away from another character to indicate that bar of soap is turning his back on the jar of cod liver oil.

Focusing on three of the plays, Much Ado About Nothing, The Two Gentlemen of Verona and Romeo & Juliet, there are three different narrators: Richard Lowdon, Claire Marshall and Terry O’Connor (respectively).

For Much Ado, the story takes place in the house and grounds of the governor of Messina, a man called Leonato, played here by a large bottle of olive oil. Soldiers returning from battle announce their intent to stay a while at the house, and the women of Messina are happy to welcome the men for a big party.

Love blossoms instantly for Hero (a shapely bottle of face wash) and Claudio (a piccolo of Champagne). Two friends throw mild and annoying insults at each other – Beatrice (a brightly coloured can of vodka pre-mix) and Benedick (a can of Bundaberg and Cola), and their other friends contrive to create rumours that they are secretly in love with each other. There’s a dark plot from a half-brother and his servant who try to break up the true lovers, but this a comedy, and it all turns out beautifully. Richard Lowdon tells the story slowly, and cleverly: the masked ball achieved by turning the various bottles, jars and cans around such that the label faces away.

For The Two Gentlemen of Verona, the two protagonists Valentine and Proteus are represented by different coloured cans of deodorant. Valentine is off to Milan, to get a better education at Court there, but his best friend Proteus is madly in love with Julia (a small urn), and so doesn’t want to leave. Proteus’ father thinks otherwise, and sends him off to Milan, so Julia and him exchange rings before they part.

In Milan, Valentine has fallen in love with the Duke’s daughter, Silvia, who is already interested in another man, but when Proteus turns up, he too falls in love – or maybe in lust – and is determined to have her.

Julia disguises herself as a man (by turning the urn upside down) and heads off to Milan to become Proteus’ page boy. There’s a lot of betrayal from Proteus to his best friend and declared love, but it’s a comedy, so it all turns out beautifully. Claire Marshall recounts the story carefully, and it’s delightful to see the servant as a jar of dried herbs, and his dog as a tiny cheese grater.

For Romeo & Juliet, the household items are gloriously introduced into the two houses of Capulet (where everyone is green) and Montague (where everyone is red). Romeo (a pocket torch) is besotted with Rosaline, but when he attends a masked ball uninvited to see her, he instead catches eyes with Juliet (a jar of lime marmalade), and the two are then inseparable. The well-known story told by Terry O’Connor is made funnier with the choices of items for the characters: the nurse is a large bottle of disinfectant (with a bold green cross on the label); the Friar a white candle. The story reaches its denouement in the Capulet crypt, but this is a tragedy, so it all turns out horribly.

There’s immense skill in selecting and then moving the many household objects as Shakespeare’s characters, and whilst there is humour outside of the text, there is plenty that remains inside it, despite turning the language from iambic pentameter to a less lyrical rhythm. And even the supposedly lifeless objects can evoke emotion from their movement and placement: it would be a hard heart to remain unmoved at the sight of a horizontal jar of marmalade and a red pocket torch, surrounded by bottles of all sizes in green and red.

It's well written, beautifully told, and brilliantly performed on the large wooden table. It makes Shakespeare approachable to a broad audience, but those who fall in love with the Bard’s words every time they’re spoken might be disappointed.

Review by Mark Wickett

Performance images - Photographer: Hugo Glendinning

'Cast' photos of Much Ado About Nothing and Romeo and Juliet by Mark Wickett.

Click here to check out our other Adelaide Festivall 2025 reviews

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.