Bad Boy

There is a certain horrible inevitability about Bad Boy. We sense with dread where it’s going. It’s a play about ‘how’ and why’, not about ‘what’. We know what. This ‘bad boy’ of the title is not a character: he is, if you like, a representative of the type of man who enacts a series of actions from which he cannot escape – or thinks he cannot. But Nicci Wilks makes him real: he stands before us in all his pathos – and violence.

The title is rich with a double meaning – one of which the play de-romanticises totally. Women are supposed to love a ‘bad boy’ (and, yes, some do, and some come to regret it) for the bad boy’s unruly, freedom-lovin’ aggressive masculinity.

That’s certainly how Nicci Wilks presents this ‘bad boy’ in an opening that is shocking and yet funny and therefore beguiling.

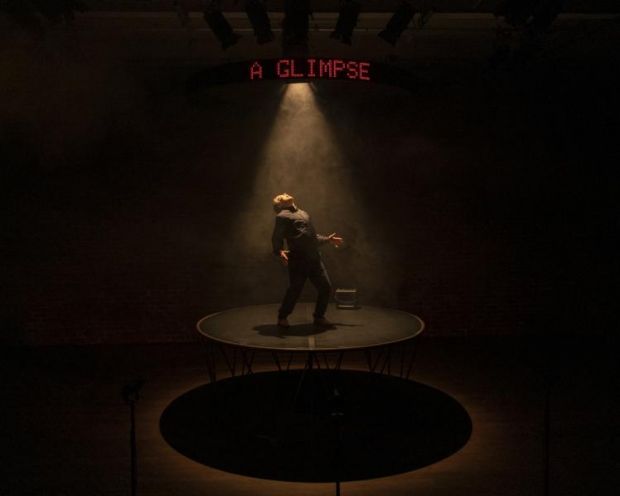

Wilks sits on a circular platform, her back to us. We know Wilks is a woman – we’ve seen her before in Cornelius-Dee collaborations – but here she’s almost unrecognisable - the hair is cropped short, and the clothes are worker butch. But – a brilliant touch – when she jumps up and faces us, she’s a caricature melodrama villain complete with upturned moustache and glittering eyes – who proceeds to deliver a high-energy spiel with much pelvic thrusting, boasting so ludicrously that it’s somehow funny about what a great, amazing fuck he is. That is what he has to offer. Come and get it. It’s ridiculous, but clearly this bad boy thinks that makes him an irresistible super stud – and curiously, it does… Until you consider it – as the music hall make-up comes off and the boy begins to tell us a story…

It's a story of a rough and tumble, ordinary sort of bloke who’s been around the traps, had a few scrapes and that, but who – coup de foudre - falls in love. Falls deeply in love. The woman in this story might be The One, but she has virtually no identity (just like women in the bad boy opening routine). She is the object of all this bad boy’s expectations – or his entitlements, or his ‘rights’. She is the empty vessel made to receive and satisfy his masculinity – and his demands, disappointments and misogyny. The last his learned early.

It's the story of a man whose misogyny provides his identity. Wilks’ near manic energy emphasises the empty shell of this man, devoid of reflection or empathy.

Cornelius’ writing is merciless. As if to emphasise deliberately the all-too-familiar tropes of this story, she adds surtitles in red, giving each sequence in the tale a descriptor – ranging from romantic cliché to blunt (‘SEX’) to whining self-pity, demands and excuses. And, of course, there is the uncanny inversion of Wilks representing the ‘bad boy’ – an unrelenting, awesome performance.

Both Wilks and Susie Dee have the sure ability to represent thought and emotion through movement and here the subtext (clear to us, but not to the storyteller) is represented to us by Wilks’ sheet physicality and it’s ever present – and it builds and builds along with our feeling of dread.

But here there are more seamless elements to the subtext and the collaboration – as Dee acknowledges in her program note: Kelly Ryall’s music choices (harshly percussive and mushy romantic) and Jenny Hector’s intricate, detailed lighting that soothes then shocks, both are not mere enhancing additions but woven into the very fabric of this piece.

It is astonishing how in the fortyfivedownstairs empty playing space, here set only with Romanie Harper’s circular platform, the completely integrated combination of text, performance, lights and sound create such a visceral experience for the audience. We are swept into a vortex, carried to the bitter end. As before, the work of this team is outstanding and unafraid.

After the show, as we caught our breath and calmed down, The Companion remarked that Bad Boy is the dark side of The Sentimental Bloke. Like CJ Dennis’ narrative comic poem, Bad Boy employs rhyming couplets - but here as the almost incantatory punctuation to each development in the story. Our ‘bad boy’ is sentimental too – in his own way – and the alarm bells ring – or they should. He didn’t think his way to what he is – and he cannot be satisfied. All the refuges and education and counselling must confront that too.

Michael Brindley

Photographer: George Jefford

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.