4.48 Psychosis

How do you describe your mental health to someone who can’t see it, doesn’t feel it, may not have ever been there? How do you talk to your doctor or your lover about how you don’t want to live any longer?

Sarah Kane’s unsettling and challenging play is James Watson’s season-ender for his and Emelia Williams’ theatre company ‘Famous Last Words’, whose year has seen a fractious love triangle (in Miss Julie, After Strindberg), a radicalised young man (in PROUD), and this, an artist using the seventy-two minutes from 4.48am to articulate how and why they will commit suicide.

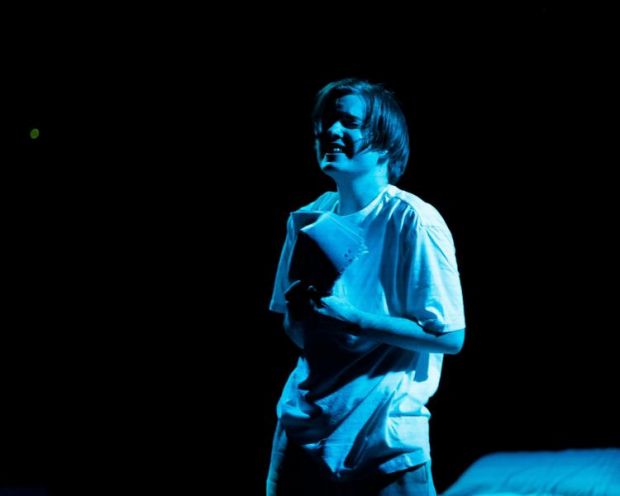

Rhys Stewart is the artist, whose expressions of pain, fear, and desire are written across Stewart’s face, in every twitch of his mouth and tremble of his hand. Stewart is outstanding in how he takes us on his journey through depression, his shades of grey blackening with every poetic word.

Arran Beattie is the doctor, then the lover – everyone else in the artist’s world, and his fluid movements between characters blurs their definition, with the artist’s questions and statements ambiguously working for any of those opposite. Beattie’s transition from clinical logic to outbursts of emotion is tremendous – there are times where we question which of these two has their sanity.

Stewart’s calm and articulate explanations of what and why make perfect sense when compared to the doctor’s ‘solution’ in medication. These two together converse and move around the stage under Watson’s step-perfect direction; we feel uncomfortable observing this, feeling this - yet we can’t look away.

Indeed, we’re captured from the start of the show by the very physical act of closing the curtain – yes, closing. before the performance begins, we’re ushered to our seats on the stage, to the back, facing out to the auditorium. It’s a large space, decorated simply by Ruby Jenkins with a raised platform and a sheet over a mattress on which Stewart writes. Beattie works to one side, as if he’s the stage technician – but then, like a doctor on a hospital ward, he pulls the curtain shut - and the intimacy is immediate.

Stephen Moylan’s lighting design adds much to that intimacy – there are times when the only light is cold white from a portable LED lamp held by one of the actors, but there are also bold washes of depression blue and magic purple. And the reliable Reggie Parker provides more than just the menace of droning sound – his always superb audio reflects the mood, marks a change, and jolts us from contemplation to action.

There are moments of theatrical brilliance – which to explain would break the spell of the performance, but they are breathtaking. There is a danger that the art is more prominent than the message, though it’s finely balanced by Watson, because what remains after the flourish is shocking.

Kane wrote this play in freeform prose and poetry, without assigning words to specific performers, or providing stage direction. Its scenes are defined in twenty-four parts, and it takes as long to perform as there are minutes between 4.48am and 6am, the time when Kane herself would often wake, and the time that Kane’s protagonist in this play plans to end their life. It’s drawn from Kane’s own experiences with depression and the medical profession – indeed, she killed herself before this play was ever staged, over two decades ago. It hasn’t aged – the questions remain relevant: how do I explain what this feels like? Why do I have to numb every feeling to survive? Is that living? And despite cheeky moments of humour, there isn’t much hope in this story.

This is not a play you ‘enjoy’ – and, like me, you might need a little time to process before you can talk about it – but it must be talked about. With its unflinching storytelling, tremendous performances, and theatrical ingenuity, it is an experience to be explored – with others.

Mark Wickett

Photographer: Philippos Ziakas

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.