The 39 Steps

ANY resemblance to John Buchan’s 1915 novel, the Alfred Hitchcock’s 1935 spy drama - or any of the subsequent film versions - is purely coincidental. Simply put, it turns the entire thriller genre on its head.

Written in 2005, this theatrical version – earning an Olivier Award for Best Comedy in 2007 and running for nine years in the West End – drew on recognisable cinematic and theatrical conventions presented in a Monty Pythonesque style, and ultimately delivered a concoction of absurd and good-humoured nonsense, unsullied with any contemporary references of Olympic-standard sex.

So, what is the recipe for this frivolous souffle? First of all, you take the complex murder and mayhem plot of Buchan’s novel and Hitchcock’s screenplay and condense all the parts to be played by four actors (in this case there were five actors plus a cameo sixth). Season those actors with numerous wig and costume changes, accent variations, and pepper them with generous doses of riotous activity and punny references to Hitchcock movies. Bake them on a stage with an equally all-purpose (and at times hilarious) set which parodies every theatre convention you can possibly think of. The result? A very funny and ultimately satisfying evening of absurd fun.

Central to director Sonia Zabala’s production are the five actors – and the team work from this cast simply sparkled. Indeed, the production would simply not have worked if the cast was not effective. This cast were of such a high standard that other elements which perhaps were less successful could be overlooked in the overall enjoyment of the production.

Played at a frenetic pace, this is no gentle parody. It is a farce, and consequently the style requires a sharp and disciplined delivery, carried with enormous physicality.

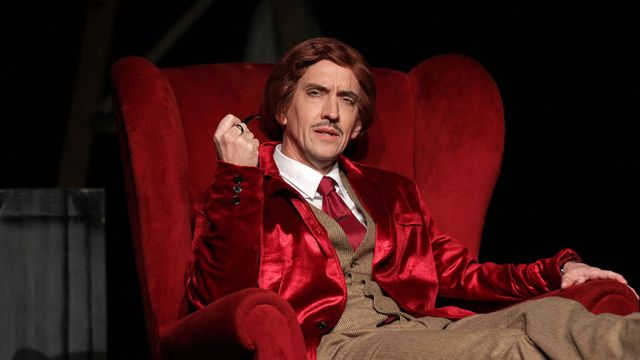

Despite an awful red wig, Matthew Palmer played the central character Richard Hannay (Robert Donat in the original film). This exhaustive and exhausting role barely saw him leave the stage – a receipt for guaranteed weight loss! His offhand delivery was perfect for the role and he clearly enjoyed himself and relished the reaction of the responsive opening night audience.

Sarah Mathiesen played the blonde heroine (played by Madeline Carroll back in 1935), and she also played numerous other roles of both genders. Playing much broader (probably in every sense of the word) characters was Jessie Devine (billed as a Clown), whose second act frenzied gender-bending scene in which she played two characters in the same scene was hysterical.

The remaining cast members – also billed as Clowns – David Lequerica and Glenn McCarthy were presented with challenges that would have daunted the most experienced of actors. Simply remembering who they were playing in each scene required an exceptional memory alone – never mind all the numerous costume, wig and accent changes.

All of the actors contributed equally to the overall good-natured nonsense, playing all sorts of roles, including swapping genders and even the odd comical inanimate object such as a streetlight and a motor car.

Managing the scene changes – done by the actors – presented some challenges for the overall pace of the production. Atmospheric music at an appropriate volume would have filled these gaps and would easily rectify this comparatively small quibble.

The opening night had some technical sound and lighting issues which will doubtless be sorted out in double-quick time, but ultimately the cast, stage action and frantic pace of delivery were the most important elements – and this worked.

Trevor Keeling

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.