Shakespeare, Aussie Style

Celebrating Shakespeare's 450th Birthday.

Celebrations are planned around the world to mark 450 years since the birth of William Shakespeare in 1564, and Australian theatres are joining the party. But how distinctive has our style of Shakespeare become? FRANK HATHERLEY recounts his own experiences dodging flying cabbages on stage and compares notes with Australia’s most lauded Shakespearean JOHN BELL

My first terrifying brush with performing Shakespeare was at The Independent Theatre, North Sydney, in 1960. The play was King Richard the Second, directed by the indomitable Doris Fitton, whose straight back and magnificently plummy voice guaranteed she knew all there was to know about staging her beloved Bard.

At that time The Independent was classified ‘Pro-Am’, though the few ‘Pros’ — mostly radio actors — were rarely paid more than travel money and were, in this production at least, outnumbered 30/1 by the ‘Ams’. I myself was a very ‘Am’, very youthful Duke of Aumerle.

Our audiences were always restless, none more than at school matinees. Cheers and jeers drowned the impenetrable dialogue.

At one notable matinee they threw vegetables. I was to escort the Queen into a court scene but when the lights came up Her Majesty, terrified, refused to leave the wings until the cabbages were removed.

When a few years later I saw the same play done by the Royal Shakespeare Company at Stratford-upon-Avon, I was truly amazed to find it gripping, thrilling and really easy to follow.

Where had Doris got it wrong? Should she have employed a more ‘Australian’ way of staging Shakespeare? Could there ever be such a thing?

***

Australian productions of Shakespeare pre-1970 tended to be pale shadows of presumed English originals. Infrequent visiting British companies gave local directors and actors jolts of creativity. In 1958 Laurence Olivier crammed theatres in Australia and New Zealand with his groundbreaking Richard III. But local audiences had little time for local productions.

Australian productions of Shakespeare pre-1970 tended to be pale shadows of presumed English originals. Infrequent visiting British companies gave local directors and actors jolts of creativity. In 1958 Laurence Olivier crammed theatres in Australia and New Zealand with his groundbreaking Richard III. But local audiences had little time for local productions.

*English actor/director Allan Wilkie (1878-1970) arrived in Australia with his actress wife in 1915. His Alan Wilkie Shakespearean Company was the first serious attempt to establish a local touring company taking the Bard throughout this wide country.

Always hard-pressed for funds, Wilkie managed to talk state governments into covering his considerable railway transport costs, thus achieving the first-ever government subsidies for theatre in Australia.

Wilkie eventually mounted 27 of Shakespeare’s 37 plays, and was only stopped by the arrival of ‘the talkies’ (and the Depression) in 1930.

*In 1951 Australian-born actor/director John Alden (1908-62 ) formed John Alden Shakespeare Productions Ltd and embarked on a national tour playing Lear, Shylock and Bottom in his own productions. It was a disaster. In an article entitled ‘Why Do We Shun Shakespeare?’ The Argus reported that Melbourne had greeted the 16-week season ‘with a monumental showing of indifference’.

*In 1951 Australian-born actor/director John Alden (1908-62 ) formed John Alden Shakespeare Productions Ltd and embarked on a national tour playing Lear, Shylock and Bottom in his own productions. It was a disaster. In an article entitled ‘Why Do We Shun Shakespeare?’ The Argus reported that Melbourne had greeted the 16-week season ‘with a monumental showing of indifference’.

‘What could do [Alden’s company] a power of good,’ sniffed The Argus, ‘would be the ideas and discipline of an overseas producer, preferably British...’

The determined, un-British Alden tried again in 1961 with backing from the new Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust. As artistic director of the first Sydney Shakespeare Festival, he played Shylock again, plus Othello and Macbeth. But, as theatre historian Frank Van Straten has noted, ‘the event was an artistic and financial disaster’.

I saw Alden that year at the Elizabethan Theatre, Newtown, blacked up as a creaky Othello with a particularly youthful Desdemona. He was, to my brash and unforgiving eye, old-fashioned.

***

John Bell, founder in 1990 of The Bell Shakespeare Company, had seen Alden on stage, too. “Yes, I remember him quite vividly,” he tells me. “He possessed the stage, a strong presence. His productions were a bit scruffy, a bit ratty. But then he had no money.

“He toured around the country on the smell of an oily rag. I admire him for that. It was inspiring the way he kept that company going with no resources, no funding. Alden and Wilkie were pioneers.”

Having laid down his marker as Hamlet at the newly formed Old Tote Theatre in Sydney in 1963, John Bell did what every ambitious young actor did at that time: he left for England. After a scholarship year at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School and four years with Peter Hall’s dynamic Royal Shakespeare Company, he came home to what he describes as “a terrible culture shock”.

Having laid down his marker as Hamlet at the newly formed Old Tote Theatre in Sydney in 1963, John Bell did what every ambitious young actor did at that time: he left for England. After a scholarship year at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School and four years with Peter Hall’s dynamic Royal Shakespeare Company, he came home to what he describes as “a terrible culture shock”.

“I was full of all that RSC stuff and raring to go. But Australia wasn’t the country I remembered. It had become far more materialistic and nationalistic, a kind of a red neck country. I was quite shocked. And I thought, well, there’s no point in trying to do English classical theatre here so I launched into a really rough vaudevillian kind of theatre at the Nimrod in Kings Cross.”

Bell founded the Nimrod Theatre Company in 1970 with partners Richard Wherrett and Ken Horler. “We were devoted to new Australian work but we did a Shakespeare every year and tried to find a way of making it Australian in a very broad sense, all corks round the hats and broad Aussie accents, a deliberate attempt to break with tradition and find a new way of doing things.

“It had a mixed reception. Some people thought, ‘terrific’. Others thought, ‘appalling, why can’t they do it the proper way, with historical costumes and rounded vowels and all of that?’ ”

Bell’s production of All’s Well That Ends Well in 1973 was notable for the cod Italian accents. “Yes, that was very, very deliberately Oz,” he says. “When we started rehearsing, all the actors came along with very polished English accents. I said, no, no, we can’t do that. Let’s use mock Italian accents for rehearsal purposes, just to break the mould.

“Then when it came the day when ‘ok, drop the Italian accents now,’ we all said, no, it’s part of the production. So we stuck with them, and it was fine, it worked.”

Even the ‘Xmas pantos’ were Oz-Shakespearean at the Nimrod. Hamlet On Ice featured Hamlet seeking a sex-change operation because he’d fallen in love with Horatio. Boy’s Own Mcbeth featured a song that recounted how Mcbeth owned a dog named Spot to which Lady Mcbeth would say “Get out damn Spot!”

Even the ‘Xmas pantos’ were Oz-Shakespearean at the Nimrod. Hamlet On Ice featured Hamlet seeking a sex-change operation because he’d fallen in love with Horatio. Boy’s Own Mcbeth featured a song that recounted how Mcbeth owned a dog named Spot to which Lady Mcbeth would say “Get out damn Spot!”

But Bell’s line of work soon deviated from “dirty radical” bardology. “When I first started in the theatre there was only one way of doing Shakespeare: the English way. All that’s disappeared completely now. You are no longer bound by any conventions. That’s a liberating thing.”

Looking back, what is his favourite Shakespeare production? There’s a long, considered pause. “The favourite one I was in, I think, was Neil Armfield’s The Tempest for the Belvoir [in 1990]. It was a very simple, very honest production. Neil had great respect for the text.”

What, I wondered, did he think of the new young directors who have far less respect for classic texts?

“I don’t mind what Simon Stone or Benedict Andrews or whoever does to the classics. They’re the new generation and they’re doing their own thing for their audience. I belong to an older generation. I still stick with the text, more or less the way it was written, more or less in the order the scenes were written.”

So is there still an Australian way of doing Shakespeare?

So is there still an Australian way of doing Shakespeare?

“I actually think that a focus on nationalism is now quite redundant. Young directors are looking to the European way of doing the classics.

“You can certainly do a play like Taming of the Shrew or Comedy of Errors and put a deliberately Australian spin on them for reasons of gender politics or social comment. That’s still up for grabs. But Australians are no longer as anxious as we were about our national identity.

“When we were more of an Anglo-Celtic culture we were trying very hard to define who we were. But now we’re such a mongrel society – and all for the better! There are many different Australian identities now and I think the theatre’s task is to try and have a conversation with all of them.

“Where is our Asian audience? Where is our indigenous audience? Where is our middle European audience? We have to talk to all of those people.

“We do a lot of work in schools. We play to 80,000 students each year all around the country. These school audiences are very largely English-as-a-second-language. More and more we’re having mixed-ethnic casts for all our productions, because unless we do we’re going to be a sort of a whitefella band rather than a company that can appeal to a much, much wider, ethnically diverse Australia.”

What’s The Bell Shakespeare Company’s biggest problem in 2014?

“Funding,” he immediately replies, thus linking him back to the travails of his predecessors John Wilkie and John Alden.

“The search for proper funding just goes on and on. We can’t possibly exist without it. We depend heavily on corporate sponsorship, on private donors, trusts and foundations. Of course government funding is not anywhere near adequate.”

Shakespeare in OZ: The 2014 Line-up.

All the big state companies are celebrating Shakespeare’s 450th birthday — except in Melbourne. Here’s our list, plus some interesting Shakespearean experiments that caught our eye.

Top pick is the Sydney Theatre Company’s Macbeth, 26 July - 27 September, with Hugo Weaving as the doomed Scottish warrior, directed by Kip Williams. Alice Babidge’s setting design is the standout feature. She’s putting the audience on the stage of the Sydney Theatre (don’t ask us how!) and the action will occur throughout the audience seating space.

Top pick is the Sydney Theatre Company’s Macbeth, 26 July - 27 September, with Hugo Weaving as the doomed Scottish warrior, directed by Kip Williams. Alice Babidge’s setting design is the standout feature. She’s putting the audience on the stage of the Sydney Theatre (don’t ask us how!) and the action will occur throughout the audience seating space.

Also in Sydney is the Ensemble Theatre’s Richard III, 24 June – 19 July, an intriguing version devised and directed by, and also starring, Mark Kilmurry, who plays a man enacting Shakespeare’s text in his flat, ‘roping in friends and potential girlfriends’.

The Sydney Festival is featured the Chicago Shakespeare Theater (sic) and their rap version of Othello: The Remix. 9-26 January at the Seymour Centre and Melbourne Malthouse Theatre’s powerful Indigenous Australian version of Lear – The Shadow King, directed by Michael Kantor, at Carriageworks, 23-26 January.

The Queensland Theatre Company is also staging that Scottish Play, 22 March – 13 April, with Jason Klarwein and Veronica Neave as Macbeth and his dangerously ambitious wife. A genuine coup is the engagement of director Michael Attenborough, hugely successful artistic director (2002-2013) of the Almeida Theatre in Central London.

The State Theatre of South Australia is staging Othello at the Dunstan Playhouse, 14-30 November, directed by Nescha Jelk.

The Black Swan State Theatre Company, Perth, is home for As You Like It, 17 May – 1 June, directed by Roger Hodgman.

The Black Swan State Theatre Company, Perth, is home for As You Like It, 17 May – 1 June, directed by Roger Hodgman.

The Bell Shakespeare Company will have three touring productions on offer: The Winter’s Tale, directed by John Bell himself; Henry V, intriguingly set during the London Blitz and directed by Damien Ryan; A Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by Peter Evans.

None of the above can match the ambition of Perth’s indigenous Yirra Yaakin Theatre Company.

In 2012 it was part of London’s Cultural Olympiad Festival where all 37 Shakespeare plays were performed in 37 different languages over six weeks at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre.

Yirra Yaakin was invited to perform six sonnets in the Noongar language, one of the oldest in the world.

Among their choices was Sonnet 18, Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? — translated as: birok kedela ngany kaaditj noona?

“It was the first time an Australian Aboriginal language was performed by Aboriginal actors on The Globe stage,” said artistic director Kyle J Morrison, “and the first time any of Shakespeare’s work was translated into Noongar.”

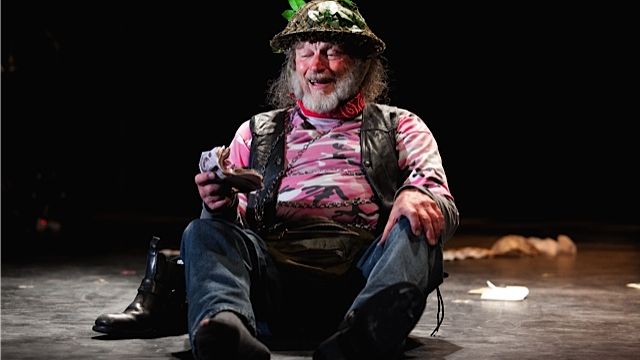

Images: John Bell in Henry 4 (2013); Allan Wilkie; John Alden; John Bell as Richard 3 (2002); Hugo Weaving in Macbeth and As You Like It.

Originally published in the January / February 2014 edition of Stage Whispers.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.