A festival is born

It is late afternoon on 24 December 1974. The residents of Darwin are preparing for Christmas Day, with many believing that the warnings of the approaching tropical cyclone Tracy would amount to nothing. Earlier in the month, Cyclone Selma was predicted to make landfall in Darwin, yet Selma had vanished north.

In his 2009 essay Divine wind, journalist Richard Evans wrote about one Darwin resident recalling a conversation about whether Tracy was a real threat: ‘We had had Cyclone Selma only a few weeks before … everyone was sick of talking about cyclones – and besides, Christmas was here.’ ‘At Christmas Eve parties,’ Evans writes, ‘the consensus was that Tracy would do what Selma had done on approaching Darwin, what every cyclone for decades had done: veer away. The police were in touch with the Weather Bureau, and had followed standard procedures to prepare for an emergency. But no-one was really worried. ‘It was still being taken lightly,’ one officer recalled.

So in spite of the warnings, wild winds and torrential rain, few precautions were taken and no evacuations took place. Instead, in true Territorian style, the festive season celebrations continued.

But between 10pm and midnight, with the wind and rain increasing alarmingly, the residents of Darwin realised that this time they were not going to be so fortunate. Cyclone Tracy made landfall directly onto Darwin at 3.30am on 25 December 1974. The highest wind gust recorded at 3.05am was 217kms per hour, shortly before the wind measuring device was destroyed by the eye of the cyclone. The Bureau of Meteorology's official estimates suggested that Tracy's gusts had reached 240kms per hour.

It would not be until between 6.30am and 8.30am on Christmas Day, that the winds and rainfall would begin to ease. As Christmas Day dawned, the extent of the nightmare the residents had endured would become apparent. The death toll would climb to 71, and 70 percent of Darwin's buildings, including 80 percent of the city’s houses, were destroyed. More than 25,000 of the total estimated population of 47,000 residents of the city were left homeless.

Basic services infrastructure, such as water, electricity and sanitation, had been destroyed or immobilised, and the population were at risk of diseases such as typhoid and cholera. Having assessed the horror of the situation, Dr Charles Gurd, the Director of Health in the Northern Territory, made the decision to evacuate residents in order to reduce the population to a ‘safe level’.

As Richard Evans writes: ‘It quickly became obvious that the city would have to be almost entirely evacuated. All “non-essential people” were airlifted out. The mass evacuation of some 20,000 people … was a vast undertaking.’ The immense cost of the relief operation and the reconstruction of Darwin would amount to more than $4 billion in today’s currency.

The Northern Territory was given self-government by Malcolm Fraser’s Commonwealth Government in July 1978, and naturally, there was talk of relocating the capital further inland to Katherine. Others, including Dr Gurd, were determined to remain and rebuild. Dr Gurd, who had operated on about 500 people the day after Cyclone Tracy, suggested celebrating the town’s revival with a festival that would draw the community together, and reflect the optimism of those determined to rebuild.

And so in July 1979, on the first anniversary of the granting of self-government, the inaugural Bougainvillea Festival was presented. The Bougainvillea Festival was a floral festival aimed at promoting the beautification of the reconstructed city, and featured events such as Home Garden contests, a Grand Parade (a floral procession through the city’s streets with floats and decorated bikes), sporting events, and a Birdman Rally.

In 1996, Darwin’s annual celebration became known as the Festival of Darwin, until 2003 when, under the direction of Artistic Director Malcolm Blaylock, the Festival was renamed the Darwin Festival to reflect its international status in the arts.

Today, Darwin Festival is the Northern Territory’s biggest festival of arts and culture. Each August, Darwin Festival combines outdoor festivities with local, national and international talent over 18 days and nights to celebrate the incomparable spirit and energy of Darwin and its sensational Dry Season.

Today, Darwin Festival is the Northern Territory’s biggest festival of arts and culture. Each August, Darwin Festival combines outdoor festivities with local, national and international talent over 18 days and nights to celebrate the incomparable spirit and energy of Darwin and its sensational Dry Season.

Selected highlights of this year’s program include:

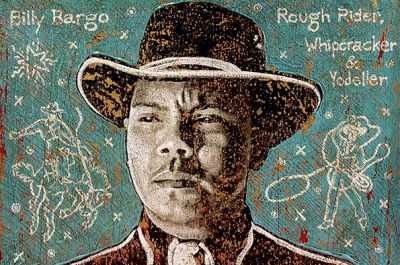

The Santos Opening Night Concert will celebrate the history of Indigenous country music in Australia with the special presentation of Buried Country. Incorporating live music, stories, art and video, singers and songwriters from across the nation and generations will be brought together, including iconic elders Roger Knox and L.J. Hill, legends Warren H. Williams and Buddy Knox, and younger artists Leah Flanagan, Luke Peacock and James Henry.

The Aurora Spiegeltent returns to the Festival, taking pride of place at The Esplanade to serve up LIMBO. From the creators of last year’s sell-out BLANC de BLANC, LIMBO is an intoxicating mix of cabaret, circus and acrobatics.

Urzila Carlson takes a break from her star turn on Have You Been Paying Attention? to offer up a hilarious night of comedy in her new show, Studies Have Shown. On the musical side, the country’s freshest new Indigenous talent Baker Boy checks into The Lighthouse, bringing his hip-hop styling and energetic flair for one night only.

Engrossing storytelling meets the visceral thrill of live boxing in Prize Fighter, a tough and unforgiving theatrical experience inspired by playwright Future D Fidel’s own life experiences as a former Congolese child soldier and refugee.

Darwin Festival

Thursday 9–Sunday 26 August 2018

https://www.darwinfestival.org.au

— Geoffrey Williams

Geoffrey will be covering this year’s Darwin Festival for Stage Whispers.

Images: The devastation brought by Cyclone Tracy upon the Northern Territory City of Darwin. Courtesy – National Archives of Australia A6135, K29/1/75/16; Dr Charles Gurd, courtesy Northern Territory Library; A float in the Bougainvillea Festival, courtesy Northern Territory Library; Darwin Festival (2017) by Elise Derwin; Baker Boy, courtesy Darwin Festival; Buried Country – Billy Bargo picture by Jon Langford.

References: Evan, R. (2009). Divine wind. Inside Story. Australian Broadcasting Commission. http://insidestory.org.au/divine-wind/

Read Geoffrey's interview with Darwin Festival’s Artistic Director, Felix Preval

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.