When the Vice Squad Censored Theatre

It was only fifty years ago that Police would raid theatres to arrest and charge actors with obscenity. Jenny Fewster, the Project Manager for AusStage, recounts a time when ending up in jail was a performance risk.

Artist Michael Gordon Brown became the only Australian visual artist to be charged with and convicted of obscenity. The Magistrate described his paintings as an “orgy of obscenity”. Brown’s sentence of three months hard labour was reduced to a $20 fine on appeal. This episode was repeated in artistic circles around Australia. Whilst the youth were becoming more avant-garde and revolutionary, there was an older generation clinging steadfastly to conservatism and Victorian morality.

In Victoria, Henry Bolte had been Premier for eleven years. A conservative Liberal, he was in favour of stiffer penalties for crimes. Under Bolte’s leadership the Summary Offences Act 1966 (VIC)was enacted. The Act contained provisions for serious offences such as assault and less serious matters such as homing pigeons, kite-flying and singing bawdy ballads.

The Summary Offences Act became the bible of the Victorian Police Vice Squad. For the remainder of the sixties the squad would keep close watch over the activities of Melbourne’s theatre-makers. By 1966 Vice Squad visits to the theatre were already so commonplace that they were a laughing stock in reviews. Howard Palmer’s review of A Cup of Tea, a Bex and a Good Lie Down (starring the angelic Gloria Dawn and Reg Livermore) mocked that if the Vice Squad pay a visit “they will laugh so much they will forget why they went”.

In 1966, two actors in San Francisco were charged with “lewd or dissolute conduct in a public place” for appearing in The Beard, a controversial play exploring the nature of seduction and attraction.

The play was published in the literary magazine Evergreen Review. In December 1968 Stefan Mager appeared in St Kilda court charged with having made an obscene article for copying the play from the magazine, which was readily available at the State Library.

Mager’s theatre company Contact Theatre wanted to produce the play before a closed audience. However, the Vice Squad raided Mager’s flat, “turning it upside down” despite the fact that he had already handed over the two copies he had made. The production never eventuated.

In January 1967 the Acting Chief Secretary declared that he would personally attend Hello Australia at the Lido Theatre Restaurant “to see at first hand whether the show is indecent”. The Vice Squad had already questioned the producer David McIllwraith and attended dress rehearsals to view the “topless dancing”. On the 5th February 1967, an officer reported that “the topless ladies, who have received official approval, are not entirely topless and behave themselves in a genteel manner. No one could possibly object to their statuesque posing.”

But it was not just the authorities upholding the morality of Melbourne at this time. In July 1968 the Women’s Auxiliary of St Vincent’s Hospital visited the Venetian Room of the Hotel Australia for a lunch time performance of Allergy, a play about a man who is allergic to adultery. The women of the Auxiliary were outraged, to the extent that a shouting match with the actors ensued and the objecting group banged their spoons on their crockery resulting in at least one broken plate. After about 45 minutes the actors left the stage “in pale resignation”, unable to continue.

America Hurrah!was the next play to be shut down by the Vice Squad, who objected to a symbolic sex act and a couple of four-letter words. In response, a private showing for invited guests took place in a private home. It was well attended by press and politicians alike. After a day or two the Vice Squad turned up at the home to question the owner and even questioned the Leader of the Opposition, Mr Holding, who had been attendance.

Editorial in The Age expressed dismay - “a private performance for adults in a living room seems to us to take the matter outside the legitimate interests of the Vice Squad. We suggest that the Vice Squad, the Victoria Police, and the State Government should stop this nonsense at once. They are making fools of themselves, which may be their own business. Unfortunately, they are acting in the name of all of us, and that is everyone’s business.”

A defiance was brewing in Melbourne’s theatre community, and following Graeme Blundell and Lindsay Smith being charged with obscenity for Alexander Buzo’s Norm and Ahmed at La Mama in July 1969, things started to heat up. The play had been produced at the Old Tote in Sydney and Twelfth Night in Brisbane without major incident. Not so in Melbourne. It was the closing line of the play that had attracted the attention of the vice squad…“Fucking Boong”. Smith was eventually convicted on obscenity charges for the seven-letter word and Blundell for aiding and abetting him. What is most surprising here is that no objection was ever raised about the use of the word Boong.

Also in July, impresario Harry M Miller’s production of The Boys in the Band was attracting attention from the vice squad at the Playbox Theatre. The play depicted a birthday party being held by a young gay man. Three actors were charged with obscenities for the use of four four-letter words. When giving evidence the officer said that only two of those words he found offensive, one didn’t worry him and a fourth the playwright “should never have used”.

It’s unclear what expertise he based that statement on, as the officer admitted to the court he was not a theatregoer, having not seen a play for the previous 15 years.

Another Constable, who was also called to give evidence, expressed a preference for musical comedies. The magistrate Mr. D. J. Kelly did not record a conviction, as he thought the offences “were of such a trifling nature as to not warrant punishment”. He said, “A conviction in this case would leave this city and this State a laughing stock”.

However the Crown appealed and the Supreme Court recorded convictions against the three actors. Harry M Miller described it as “a dreadful waste of public money” and stated that the “public who buy tickets are the arbiters.” Thumbing his nose at the establishment, Miller announced that he would next produce the controversial musical Hair.

Leading playwrights met in 1969 in a back garden in Carlton to forge a battle plan.

Present were members of the Australian Performing Group, Graeme Blundell, Lindsay Smith, Jack Hibberd, Alexander Buzo, John Romeril and journalist John Larkin, who reported the meeting in his column in The Age under the title “Headed for a 4-letter paradise”. Those present “acknowledged the situation between them and the authorities has reached a state of confrontation…they have said that they will keep writing and keep playing and keep being arrested.”

Later that week the Australian Performing Group performed a short play by John Romeril entitled Whatever Happened to Realism. The play examined the irrationality of censorship and its effect on the theatre, for practitioners and audiences. It culminates in what John Larkin described as a “four-letter paradise”. On the 20th December, only four days after the meeting in Carlton, nine actors were arrested and charged with obscenity. Those present in the audience marched to the police station, chanting four letter words. Police reinforcements were called in.

As the sixties came to an end the Victorian Police, including members of the Vice Squad, found themselves coming under some unwanted scrutiny. Allegations were made that corrupt police were paid to allow the illegal abortion industry to flourish. Officers were paid up to $150 a week in bribes at a time when a detective's weekly wage was $122. Several officers later served time.

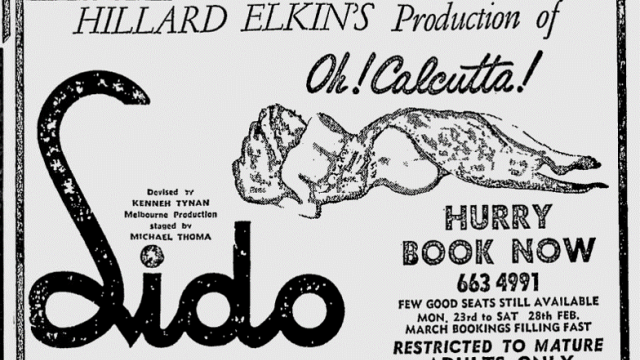

David McIllwraith, owner of the Lido, also found himself coming under some scrutiny for his proposed production of Oh! Calcutta! at this time, a “sex-related” avant-garde theatre revue that divided opinion. Robert Helpmann said. “I saw Oh Calcutta! in New York – that Kenneth Tynan thing – and I kept thinking ‘Oh, I wish they’d put their clothes on.” Actors’ Equity in Australia recommended that “members should not take part in it”.

The Attorney General lodged a writ accusing David McIllwriath “of wrongfully and illegally conspiring to show an indecent exhibition and corrupt the public morals, and intending to aid and abet male and female actors to expose their naked persons.”

Mr Justice Little in the Supreme Court described the show as “filth” and granted the injunction. What would have been the first production of the show outside the United States was closed before it opened. 80 cast and crew were dismissed and McIllwraith claimed that he was out of pocket to the tune of $200,000. Despondent, he put the Lido on the market.

Miller pressed on with his production of Hair. He had shrewdly used the controversy of the show to generate advance publicity in Sydney and also ran a number of previews for invited guests prior to the public opening. The NSW Chief Secretary, Eric Willis, was invited to one of these previews. Miller minimised the shock of the nude scene at that performance by keeping it to approximately forty seconds. Miller said “if you’d dropped your programme on the floor you wouldn’t have seen it”.

Later Reg Livermore was quoted as saying “the nude scene is nothing to write home about…it is backlit, so you’d have to have the eyes of Superman to claim with some certainty you’d seen anything.” Reg tried not to draw attention to himself by choosing to stand next to one of the cast’s tall, black men…”nobody looked at me,” he said. The show was a runaway success and ran without intervention for nearly two years.

Later Reg Livermore was quoted as saying “the nude scene is nothing to write home about…it is backlit, so you’d have to have the eyes of Superman to claim with some certainty you’d seen anything.” Reg tried not to draw attention to himself by choosing to stand next to one of the cast’s tall, black men…”nobody looked at me,” he said. The show was a runaway success and ran without intervention for nearly two years.

On the 21st May 1971 Hair opened at Melbourne’s Metro Theatre. The Vice Squad was absent and raised no objection despite full frontal nudity and four letter words. The only legal incident raised was that Miller had breached the Health Act’s fire regulation for permitting a naked light on stage when the theatre was open to the public. Hair ran until February 1972.

The Vice Squad now seemed to be turning its attention to other vices. In 1976 an article appeared in The Age under the banner “Melbourne: It’s too much for the Vice Squad” describing the difficulty that the squad had “guarding the public from the evil of 180 massage parlours, a prostitution population of 2000, a dozen sex shops and a booming pornographic book market.” There was no mention of the theatre.

You can find information on all of the productions and newspaper articles in AusStage, Australia’s online resource for live performance in Australia.

Originally published in the November / December 2016 edition of Stage Whispers.