Louis Nowra: The Playwright Born To Shock

MARTIN PORTUS profiles LOUIS NOWRA, the remarkable talent behind the Australian classic Cosi and much more.

A writing career seemed unlikely for young Louis Nowra. Raised in a Housing Commission paddock suburb north of Melbourne without any sewerage, ignored by his truck driving Dad, belittled by his unhappy Mum, little Louis couldn’t really read until he was 17.

He was scalped in a brutal boyhood accident which for four years left him unable to properly talk, think or write, dismissed by his teachers as an imbecile.

Nor did it help that on what was to be the date of his birthday, a few years before he was born, Louis’ mother shot dead her own father. He always wondered why she was especially moody on his special day; when he turned 21 in 1970, she told him.

And by then both his grannies were mad, and institutionalised in an asylum which, conveniently, was just next door.

But by then, the electrics of Louis’ brain had miraculously reset; and he’d completed reading his first book – Lolita. He finally understood how sentences were made.

“Every day, I think how did I get here?” he says. “How did I get to be writing books and plays and going to Hollywood, how? I am lazy but I have this other persona that does all the work. And I’ve never reconciled my upbringing with this persona who has done so much.”

Nowra went on to plumb his bizarre childhood for many of the themes, characters and theatrical excesses of his plays. Years later, in 1992, the Melbourne Theatre Company premiered Summer of the Aliens, a play directly about his childhood; if, he says, a little more upbeat and romanticised. Louis played himself as the Narrator. The play was a hit and is still widely studied in schools. So too was his next play about staging Mozart’s opera Cosi fan Tutti in a mental asylum.

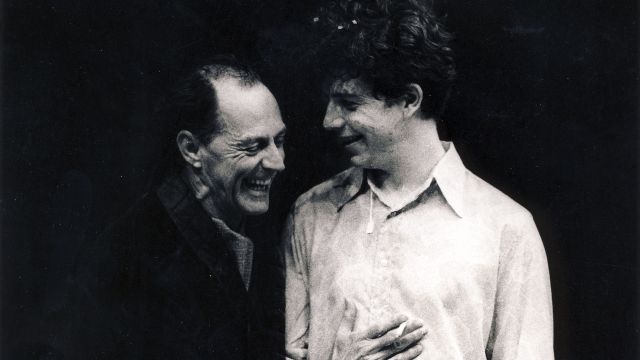

Premiered also in 1992, at Sydney’s Belvoir theatre, Cosi draws on his real experience as a young man when he was employed to direct a musical with mental patients. Testament to the healing power of theatre, Cosi is now Nowra’s most produced play and the subsequent film was highly acclaimed. Nowra wrote the screenplay and, heading a cast of Australian favourites, Ben Mendelsohn played the role of Nowra the director.

Madness and amnesia, both personal and national, and the outsider, whether sexual, racial, immigrant or fringe-dweller, were to become big themes for Nowra. Since childhood, he’s despised all racism and all group think.

An uncle, Bob Herbert, a playwright himself (No Names, No Pack Drill), took young Louis to the overseas musicals he was directing for J.C. Williamsons. Their beauty, the songs and vivid costumes conjured another world for Louis – his plays later plundered the same costume box for that escape into theatrical excess.

Not that there was much of that in the early days of the influential if spartan La Mama, then Melbourne’s hub of new Aussie writing. For Nowra, this world was much too blokey and dogmatically leftist. He, on the other hand, was living with a part Aboriginal drag queen, taking hallucinogenic drugs and trying to copy the style of Britain’s outrageous writer of farce, Joe Orton.

But La Mama staged his first plays. One Nowra remembers as “the worst Australian play ever written – and that’s saying something – so I realised I had to learn to write.”

It was the mid 1970’s and success, without any formal training, somehow came quickly. His work was admired in Sydney, where Nowra admired its more theatrical, higher production standards.

“People at the Australian Performing Group (in Melbourne) thought Sydney was poofta-ville with theatre run by a gay mafia. I thought, well, if that’s a gay mafia then they can run it for as long as they want. I worked there with the best directors – Jim Sharman, Rex Cramphorn, Neil Armfield and later David Berthold.”

These early plays were vivid, fantastical and, interestingly, set internationally. Inner Voices is about an imprisoned 18th Century Russian prince who can’t speak; Visions is about a corrupt and despotic couple ruling 19th Century Paraguay – Nowra loves stories about bad taste presidential couples; and The Precious Woman is set amongst the warlords of China in the 1920’s.

“I was impressed by Elizabethan theatre which could be set anywhere,” he says. “And so confused by Australia and the Ocker, and how to write about it, especially not being a social realist. And I was very influenced by German films.”

“So much of Australian theatre is confirming the audience’s view of the world whereas my thing is the opposite – I want to be shocked or shattered. Australian theatre has to be larger than a living room, bigger and more visually exciting. ”

And so when Nowra did finally write plays about Australia – notably during a long residency with Jim Sharman’s famed Lighthouse ensemble in Adelaide – they were usually set outdoors, often around an affluent pastoral family and with powerful historical resonances.

“But I was still trying to find a way for Australians to talk without it being aphorisms, put-downs or attempted wit. And so it was a journey which took me quite a while, really until Capricornia.”

Curiously, Nowra invented his own native idiom for the forgotten settlers in The Golden Age, lost for generations in the Tasmanian wilderness. Nowra had been giving a talk at Monash University and in the teacher’s room someone told him the story of this lost tribe.

“He was halfway through and I’d already worked out the opening scenes in my head.”

The tribe speak a rich Aussie word-mash of Cockney and Irish slang littered with poetic obscenities. After their discovery, they try to preserve their language and culture but, one by one, by then institutionalised in Hobart, they all die off. Meanwhile the play’s themes of racial superiority and lost community and values take the action sweeping across the killing fields of World War I.

Nowra was, by then, near unique as an Anglo-Australian writer who introduced indigenous characters and storylines into his plays and novels. Indeed, it’s tempting to see The Golden Age in 1985 as part metaphor for the Aboriginal experience.

“No, I was more interested in what happens when you are cut off from another world, and how you create your own. But that Aboriginal thing was obviously in the background.”

This remarkable play was popular but the critics savaged it. And Nowra was so bruised, he spent years instead writing telemovies, like Displaced Persons about immigrants locked up in Sydney’s old North Head Quarantine Station, and Lizard King, about a French boy lost in the desert.

Capricornia, a landmark touring Bicentennial production which directly tackled Aboriginal storytelling with Aboriginal actors in lead roles (including Nowra’s then partner, the late Justine Saunders). Based loosely on Xavier Herbert’s novel of life in the Northern Territory, it was the sort rolling landscape epic which suited Nowra. Here he brought a warmth and empathy to his characters, defying critical mumbles that Nowra’s work can be cold and remote.

Since then, in 1988, Nowra swore he’d never read a critic. It’s not because they were critical of Capricornia but, rather, because they were ignorant in not finding the dramatic faults which Nowra knew to be there.

“The great thing about it was that I found my father’s voice (as an Irish storyteller). I found an ease about the Australian vernacular for the first time.”

This new empathy continued with the autobiographical Summer of the Aliens and Cosi, despite his painful childhood. A few years later, he wrote a more accurate rendition of his young life in the much applauded, The Twelth of Never, the first of his two memoirs.

“I think you become aware of people, their strength and weaknesses, as you get older. And with plays moving to smaller casts (for economic reasons), I become more interested in their psychology.”

“And I began to find I was warmer to human beings. From the age of seven, I’d always disliked them: adults were monsters … violent and cruel to one another. And so with Aliens and Cosi, I began to see a warmth that in a play like Radiance really shone through.”

Radiance, premiering at Belvoir in 1993, began life when indigenous actors Lydia Miller and Rhoda Roberts started chased Nowra to write them a play. Rachel Maza was added and the story of three contrasting half-sisters, re-united at the home of their deceased mother, was born.

“When we sat down at the first day of rehearsal they made sure that the word, Aboriginal, was never mentioned in the script.”

Yet a significant theme of Radiance is the dispossession of the late Aboriginal mother, with her house about to be claimed by a creditor and she long rejected by those of her own country on the island across the mudflat. At the end, the sisters burn down the house.

Aboriginal story or not, Radiance has been performed widely from India to Czechoslovakia.

“I was bought up by women soRadiance was like overhearing my aunties talking about local gossip. Unlike men’s talk, women’s talk was really personal and melodramatic.”

For the film in 1998, Nowra lost his battle with director Rachel Perkins who wanted the sisters talking over the kitchen sink – so much does he loathe domestic naturalism. But to compensate, at the finale, the sisters got to wear mad wigs as Nowra’s theatrical metaphor for them starting new identities. And the house in the film was set not in the outback, as preferred by Perkins, but in one of Nowra’s favourite settings, in the North Queensland tropical rainforests amongst the cane fields.

Radiance was the first commercial film directed by an Aboriginal, man or woman, and to feature three indigenous leads. Itgarnered six AFI nominations and won Deborah Mailman – playing the younger sister with, says Nowra, a “smile that would light up a room” – the AFI Best Actress Award.

Louis Nowra went on to explore other Aboriginal stories in his work, and cross-racial relationships are a constant in his plays and in original screen plays like Map of the Human Heart and Heaven’s Burning.

A ground-breaking writer for Australian theatre in the 1970’s, he remained prolific and popular on stages throughout the 1990’s and into the new decade.

There is, arguably, no other Australian writer who has transformed himself into such an adaptable jobbing writer – of plays, screenplays, radio plays, TV documentaries and films, memoirs, short stories, novels, biographies, essays, neighbourhood histories and profiles, criticism and journalism.

And all from a once withdrawn teenager who, for so many years, couldn’t speak or write a sentence.

Images: Cosi with Barry Otto and Ben Mendelsoh; David Field and Ben Mendelsohn in Cosi - Belvoir 1992.; Damon Herriman and Sara Zwangobani in Summer of the Aliens - STC 1993; The Golden Age – NIDA; Melita Jurisic in The Golden Age- Playbox 1985; and Rhoda Roberts, Rachel Maza and Lydia Miller in Radiance - Belvoir 1993. Images courtesy of Currency House.

Louis Nowra spoke to Martin Portus for a State Library of NSW oral history project on leaders in Sydney’s performing arts; the full six hour interview is available on the Library’s website. Click the links below to listen.