When Cowboys and Indians Ran Wild on Australian Stages

In the late Nineteenth Century the Wild West proved a sensation for Australian and New Zealand theatre audiences. In those days respect for indigenous people and animal rights were not a consideration. Jenny Fewster from AusStage reports.

On the 8th December 1890, the Britannia docked in Melbourne. On board was an American named Doc Carver accompanied by his wife. Travelling with him, although in steerage rather than cabins, were several Native Americans and Mexican Vaqueros.

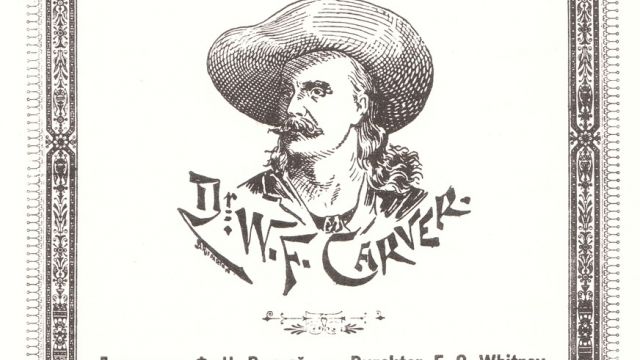

A household name in American and Europe, Carver had been a plainsman in America’s West briefly in the 1870s. It was here that he claims to have honed the shooting skills he demonstrated the world over in the 1880’s.

Carver’s skill earnt him the titles of Champion Rifle Shot of the World and Spirit Gun of the West. He was invited by The Prince of Wales to demonstrate his shooting abilities for the Royal Family at Sandringham. The Prince presented him with a gold horseshoe scarf pin studded with diamonds.

In 1883 Carver went into partnership with Buffalo Bill Cody. The pair parted company after their first season. For several years both Carver and Cody toured shows entitled Wild West, and soon law suits and countersuits were drawn, chiefly over the right to use the “Wild West” name which both men claim to have coined.

From Europe, Carver brought his show Wild America to Melbourne. It opened in the Friendly Society’s Gardens (the current site of Olympic Park) on 23rd December 1890.

Wild Americawas touted as an exhibition of life and adventure as experienced on the plains of America. It took up in excess of two acres and included a “genuine” Indian Village as well as daily performances of shooting from horseback, lasso throwing, Indian war manouevres and buck-jumping.

This interest was further fuelled by the Battle at Wounded Knee in South Dakota between the U.S. Cavalry and the Native Lakota peoples, at which over 200 Lakota lost their lives. Carver and his Indians were asked to make a public comment and on the 1st January 1891 The Argus published a piece entitled The Indian Risings in America. What Dr. Carver and his Indians say.

Carver had his own local battles. Two employees of a rival touring show were fined for assaulting his agent, in a skirmish over his Indians.

Carver attracted large interest when he took his show to Sydney’s Moore Park. Three teenagers were fined 20 Shillings (or on default, 21 days gaol) for breaking branches from a tree in Moore Park in order to gain a clear view behind Wild America’s 9ft galvanized fence.

After ten weeks, Carver travelled back to Melbourne, making the acquaintance of Australians Alfred Dampier, and along with Garnet Walch undertook a successful business partnership.

Dampier and Walch wrote, in their typical style, a melodramatic piece, as a vehicle for Doc Carver, called The Scout. It opened on 9th May 1891 at the Alexandra Theatre (now Her Majesty’s).The two Australians wrote an American cowboy and Indian piece set on the Western frontier, full of stereotyped characters: Dr Carver – essentially playing the character he portrayed to the public; Brenda Marvel – the feisty, and fiercely capable young, love interest, played by Alfred Dampier’s daughter Lily; Brenda’s long lost sister Alice, renamed Neamata by the ‘vicious’ Indians who kidnapped her at the tender age of five; the nervous Irishman, Patrick O’Finnegan; the blundering Dutchman, Hans Donderheim; and the African American servant, Napoleon Primrose Snowball.

The storyline was formula: boy and girl (or middle aged man Carver and 21 year old Lily Dampier) are in love, in this case betrothed, boy loses girl (when she is kidnapped by the vicious Indians), boy rescues girl and everyone (except the villains) live happily ever after because along the way girl has found long lost sister and inherited a fortune.

So if it wasn’t the relatively weak storyline or characterisation that made The Scout a massive success, what was it?

As The Argus reported it on 11th May 1891:

“What dramatic situation could compare with this huge tank 40ft long and 12ft broad by 9ft deep, which occupies the whole back of the stage, and is at the will of the scenic artist, a placid lake in which live ducks swim about, or a rushing river, in which cowboys, Indians, and horses shout and struggle and splash in admirable confusion?”

The Hobart Mercury’s report, under the headline “Sensationalism Run Mad” (May 18 1891) described the second act:

“The scene represents an Indian encampment, and we have the satisfaction of seeing “the braves" erect a teepee, for the special benefit of Miss Lily Dumpier, who has been taken prisoner. The faithful Carver paddles his canoe - a real birch bark one - across the lake. To brain the Indian sentinel and gag and bind the villain are to a man of his physique but the work of a few minutes. The braves are away banqueting on dog. The horses are concealed in the gorge of the canyon on the O.P. side. What remains but to fly? Next minute Miss Lily Dampier canters across the stage on a neat little brown pony, and the Evil Spirit of the Plains follows on a barebacked and bony broncho. A moment later and the pony reappear, picking its way carefully across an aerial bridge high up in the borders, and as the prairie belle reins up on the opposite side, Dr. Carver, on his broncho, attempts the perilous pass. But the alarm has been given and the Indians are swarming the rocks and popping away with rifles and revolvers at the fugitives. Miss Dampier for a moment stems the onslaught with a nickel-plated Derringer. The broncho is half-way across, when there is a rush and a scream, the whole bottom of the bridge gives way, and drops down the broncho 14ft into the lake, and swims away snorting and screaming, leaving the rider hanging tooth and nail to the parapet. The effect is startling in the extreme and it took with the audience so much on Saturday that they applauded and whistled and yelled for nearly 10 minutes in a vain attempt to obtain an encore.”

Such was the popularity of the show that Sarah Bernhardt, who was appearing as Cleopatra at the Princess Theatre at the time, attended amatinée performance and occupied seats in the centre of the dress-circle.

On 20th June 1891 Carver’s newest production The Trapper replaced The Scout at the Alexandra. Again penned by Dampier and Walch, The Argus reported on the 22nd June 1891: “Both are pieces constructed on precisely the same lines, and both rely for their sensations upon the same accessories. Needless to say, the foremost of these accessories is gunpowder.”

On 20th June 1891 Carver’s newest production The Trapper replaced The Scout at the Alexandra. Again penned by Dampier and Walch, The Argus reported on the 22nd June 1891: “Both are pieces constructed on precisely the same lines, and both rely for their sensations upon the same accessories. Needless to say, the foremost of these accessories is gunpowder.”

By 1893 America was in the grip of an economic downturn and Carver was forced to disband his troupe and sell his stage effects. By 1894 a depression was being felt in Australia too and in June of that year Dampier filed for insolvency.

Carver put together a smaller show to which he added a diving horse in 1894. Over the next few years Carvers’ other acts were eliminated, and the horse diving exhibition became his primary endeavour. The diving horse act was continued by his family after Carver’s death in 1928 but was eventually closed down due to pressure from animal rights activists in the 1970s.

In 1892 Dampier’s daughter Lily went through a scandalous divorce case with fellow actor Watkin Wynne, adding to his woes. Dampier returned to the stage but his health was deteriorating after a fall through a stage trapdoor in New Zealand in 1893. He retired after a farewell performance of Robbery Under Arms in Sydney on 10th November 1905 and died in Sydney in 23rd May 1908 of a cerebral haemorrhage.

You can find more information in AusStage (www.ausstage.edu.au), Australia’s online resource for researching live performance in Australia.

Click here for more Australian theatre history.

Originally published in the March /April 2016 edition of Stage Whispers print magazine.