Stage to Page 2018

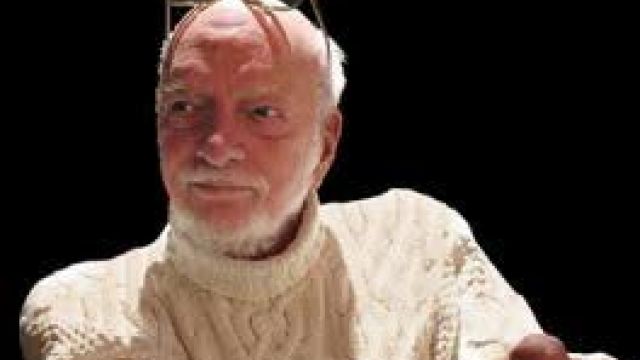

Sense Of Occasion – Harold Prince (Applause $29.99)

The one thing that can be guaranteed about a Harold Prince production is its attention to detail; the design, costumes, choreography, orchestrations, sound and lighting are always immaculate, therefore it’s hard to understand why Sense of Occasion lacks so much of it. Acclaimed and honoured for his artistically challenging productions of West Side Story, Fiddler on the Roof, Cabaret, Company, Follies, Sweeney Todd, Evita and The Phantom of the Opera, this memoir looks back on Prince’s six-decade career in the American Theatre but there’s not enough detail, especially of the later shows. Also, the book is a bit of a cheat as it reprints the entire 200-page text of his 1974 book Contradictions: Notes on Twenty-Six Years in the Theatre (long out of print), admittedly with up-to-date footnotes in which he corrects mistakes and changes his mind on some things he had written, leaving only 100-pages to discuss the rest of his career, including two of his most successful productions, Evita and The Phantom of the Opera.

Prince began his career as a producer, working out of his mentor George Abbott’s office. It was a sidebar to what he really wanted to do, which was direct. His first three successes (with producing partners Frederick Brisson and Robert E. Griffiths) were the Richard Adler and Jerry Ross hits The Pajama Game and Damn Yankees, and Bob Merrill’s New Girl in Town, all directed by Abbott. He notes the capital investment of the first two was just over $160,000 dollars, a figure he wryly says these days would barely pay for shoes and wigs on a Broadway production.

Next came the ground-breaking West Side Story, a show that received favourable but lukewarm reviews and only won one major award, a Tony for Jerome Robbins’ choreography, but as of 2015 has returned 1521 per-cent on its original investment. Fiorello, Tenderloin, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum andShe Loves Me followed before he hit the jackpot big again with another Robbins choreographed vehicle, Fiddler on the Roof, which played a record (for the time) 3,242 performances.

Prince got his first chance to direct on his own production of John Kander and Fred Ebb’s Cabaret. It was the beginning of his series of ‘concept’ musicals, which continued with Stephen Sondheim’s Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd and Merrily We Roll Along, not all of them hits, but all of them game-changing. He had his share of also-rans which included A Family Affair, Baker Street, Flora, the Red Menace, and “It’s a Bird…It’s a Plane…It’s Superman”.

Three quick flops in the eighties, A Doll’s Life, Diamonds and Grind, are cobbled together in one chapter before we get to the legendary The Phantom of the Opera, which has racked up 25 years in the West End and similar on Broadway. Other notable productions of this period were Kiss of the Spider Woman, a 1994 revival of Show Boat, Jason Robert Brown’s Parade and LoveMusik, a concept based on Kurt Weill’s marriage to Lotte Lenya, starring Lenya and featuring his songs.

Prince claims he has always been hooked on German expressionism, Kabuki, Meyerhold, Piscator and Brecht. Other influences, especially in the late fifties and early sixties, were Joan Littlewood’s The Hostage, Lionel Bart’s Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be and the Taganka Theatre, Russia.

Prince has never chosen a subject to please an audience, in fact he says that frequently he goes out of his way not to consider them, but he does look for something that’s innovative and defies convention. He abhors feel-good or mindless musicals. The only ones he likes are Bye Bye Birdie and Guys and Dolls. He also acknowledges his penchant to find a metaphor for his projects has sometimes killed their chance of success.

Although he has produced and directed plays (Take Her She’s Mine was his biggest hit), his forte is musical theatre.

There’s little of Prince’s private life and he’s not into gossip. The closest he comes is telling the oft repeated Madeline Kahn quip after the first night of On The Twentieth Century. On the road and in previews he had been trying to get her to maintain a performance from one night to the next to no avail, but on the opening night she performed brilliantly. He rushed backstage to tell her and she said, “I hope you don’t think I can do that every night,” and she didn’t. She was replaced nine weeks later by Judy Kaye. Prince believes had Kaye opened the show it would have run twice as long. It’s a similar situation when he talks of not waiting until Julie Andrews was available to star in She Loves Me; good though Barbara Cook was, Andrews was a name and would have sold the show.

The text does throw up some interesting facts - Peter Gennaro choreographed all of Chita Rivera’s dances, including “America”, in West Side Story, original lyricist Lillian Hellman thought Prince’s 1974 Candide was “a piece of trash”, A Little Night Music’s cast recording was the first non-rock musical to recoup its budget, Pacific Overtures lost its entire capitalization, and he believes musicals about prostitutes don’t work but that Tenderloin would have been a hit if it had been produced by David Merrick and directed by Gower Champion.

Prince comes across as arrogant, opinionated, perverse, but a man with one of the most brilliant minds to have ever worked in the theatre. A giant amongst his contemporaries, there’s no doubt he helped change the direction of the Broadway musical. This may not be the definitive book of his achievements, but it’s a pretty good start. It comes with B&W photos, an appendix of all his productions, and a comprehensive index.

Unmasked A Memoir – Andrew Lloyd Webber (Harper Collins $25.50)

Unmasked A Memoir – Andrew Lloyd Webber (Harper Collins $25.50)

Andrew Lloyd Webber, who has just turned 70, has resisted writing his autobiography for years until constant pressuring from friends and family, and badgering by the late literary agent Ed Victor “to tell your story your way”, persuaded him otherwise. All I can say is thank God they did. Not only is it funny, wry, and hugely engaging, it’s the best composer autobiography I’ve ever read.

A doorstopper at 500 pages, yes (and it only goes up to Phantom’s first night), but it’s a compelling page-turner of a monumental career in musical theatre. Coming of age as he did in the Carnaby Street/Swinging Sixties era of Britain, everyone from The Beatles to the Royal Family plays a part in this lively memoir.

He was born in 1948 to a piano-teaching mother and a father who was Professor of Composition at the Royal College of Music. When his Granny Molly took him to see My Fair Lady and West Side Story he was hooked on musical theatre. The attraction only increased after seeing the movies of Gigi and South Pacific (the latter four times). But the movie that resonated deeply with him was Elvis Presley’s Jailhouse Rock. It’s no surprise that he later became an expert at the fusion of musical theatre and rock.

Lloyd Webber lived in a top floor flat in Harrington Court, South Kensington, which he says in the sixties “redefined the ‘B’ in Bohemian.” In the nursery he built a toy theatre he called the Harrington Pavillion and wrote songs for productions he staged there, pressuring his brother Julian to help.

Early influences came from his risqué Aunt Vi (the book is dedicated to her) who taught him how to cook and wrote the first gay recipe book, with a “Coq and Game Meat” section titled “Too Many Cocks Spoil the Broth”.

Meeting Tim Rice in 1965 through his agent, they began collaborating almost immediately. Their first effort The Likes of Us didn’t get up, but their second did. Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, based on the Book of Genesis story, was a 20-minute rock-cantata written for Colet Court School, Hammersmith. It went on to be expanded many times and gave them their first smash headline (“Pop Goes Joseph”) in the Sunday Times, following a production at the Edinburgh Festival. According to Lloyd Webber “it’s the colloquialisms that make Joseph so great.” It’s difficult to top Rice’s clever turn of phrase - “Potiphar had very few cares/He was one of Egypt’s millionaires/Having made a fortune buying shares/In pyramids.”

Next came one of the most important meetings of his career with Southern Music boss Bob Kingston, who gave him a lesson he’s never forgotten. Never give away the “Grand Rights” to your show; from that moment Lloyd Webber never did, making him, and his investors, very rich.

Always fascinated by the tone colours of Benjamin Britten and Richard Strauss, at the suggestion of his father, he enthusiastically took a course in orchestration. At the same time he married his childhood sweetheart Sarah Hugill, and bought a house in the country, Sydmonton, with a church annex which became his tryout theatre for the next forty years.

Jesus Christ Superstar’sthree-note signature theme was written on a napkin at the restaurant Carlo’s Place in Fulham Road. For the Superstar single, Lloyd Webber cheekily asked MCA Records for, and got, a symphony orchestra, soul brass section, gospel choir, rock group, and a bluesy vocal courtesy of Murray Head. Prior to the recording sessions Lloyd Webber found difficulty in finding rock musicians who could actually read music. The final line-up included keyboardist Rod Argent of the Zombies and guitarist Gary Moore of Tin Lizzie, who went on to play on many of Lloyd Webber’s recordings.

The album was a spectacular success, especially in America, which saw pop-promoter and impresario Robert Stigwood mounting concert tours of it throughout the country, a blueprint for what became the global musical of the future.

Like Superstar, Evita, the story of the life of Argentina’s Eva Peron, was first produced as an album which attracted the attention of Broadway producer/director Hal Prince. Its Broadway opening received withering reviews but went on to complete, according to Lloyd Webber, “the biggest volte face of the media elites in Broadway history”, when it won seven Tonys thanks to the first-ever TV advertising campaign concocted by Stigwood.

The indestructible Cats followed, with one of Lloyd Webber’s most indestructible melodies. Webber had written a tune for a musical that was to be about Puccini and Leoncavallo, which he deliberately made Puccini-esque, so he played it for his father who was an expert on Puccini’s scores. After he played it a second-time, Lloyd Webber asked his father did it sound like anything, and his father said, “Andrew it sounds like a million dollars, you crafty sod,” and so ‘Memory’ was born. When Barbra Streisand recorded it, she sang it live in the studio with an orchestra of 80 musicians. It was the first time she had sung live in over a decade and was the catalyst for her to start touring again.

With the production of Cats undersubscribed, Lloyd Webber mortgaged his Sydmonton Estate to get the necessary finance, but when star Judi Dench (Grizabella) snapped her achilles tendon during rehearsals and Elaine Paige was seconded to replace her, and with a bomb scare on opening night, the project seemed doomed. But it wasn’t. The reaction was unprecedented from the critics and public and the show went on to run 21 years in London and 18 on Broadway. The Cats eyes logo is the highest selling T-shirt in the world, after the Hard Rock Café.

Cats was also where Lloyd Webber met his muse and second wife Sarah Brightman and found his musical theatre soul-mate Cameron Mackintosh, “the only Brit who loves musicals as much as me.”

Lloyd Webber’s longest running show The Phantom of the Opera had its genesis when Brightman was asked to appear in a melodrama version of the story by Ken Hill, with an opera pot-pourri score. Lloyd Webber wrote and recorded the title song with Brightman, but on a trip to New York came across a 50 cent copy of the original Gaston Leroux novel, read it, and realised the story had the potential to be something great. He was not wrong. The musical has now run 32 years in London and 30 years on Broadway, where it has become the longest running musical in Broadway history.

The second-act of Phantom was written while Lloyd Webber and Brightman were holidaying at the Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, after the Sydney opening of Cats. At one time Alan Jay Lerner was attached as lyricist but he died before completing any work.

Some projects failed, Jeeves being one of them, but the musical found a new lease of life in the nineties. The one-woman musical Tell Me On A Sunday was cannily coupled by Mackintosh with Lloyd Webber’s Variations on Paganini’s A Minor Caprice as Song and Dance, and his love of the children’s book Thomas the Tank Engine morphed into the roller-blade musical Starlight Express, which is still running after 30 years in a purpose-built theatre in Bochum, Germany.

His fascination for the 7/8 time signatures springs from his time turning pages for prize-winning pianist and another Harrington Court resident, John Lill, when he was playing Prokofiev’s 7th Piano Sonata. Every one of his musicals has included a song or section in this time-signature. There is even a joke in Phantom’s scorewhich has only ever been laughed at once, by conductor Lorn Maazal. He also has a fondness for 5/4 and every show includes a song in that time signature too. Sunset Boulevard is the only musical title song written in 5/4.

There’s just enough gossip to make this book spicy (Tim Rice, a bit of a stud, bedded every girl who ever played Mary Magdalene), a lot about the nuts and bolts on how the productions were put together (the lead up to Cats opening is nail-biting), and a little of the personal (the race to get Sarah H to hospital before she died when an illness was misdiagnosed).

Lloyd Webber intended to write his memoirs in one volume but his verbosity got in the way, so everything post Phantom will just have to wait for volume two, if and when he gets around to writing it. The book also includes only minor references to his other passions, architecture and Pre-Raphaelite and Victorian art, which he says belong in another volume.

Lloyd Webber, with his rock-operas and sung-through works, changed the face of musical theatre. This book scrupulously and delightfully tells you how he did it. It comes with coloured and B&W photos, an appendix, and an index.

Must Close Saturday – The Decline and Fall of the British Musical Flop by Adrian Wright (Boydell Press A$51.91).

Must Close Saturday – The Decline and Fall of the British Musical Flop by Adrian Wright (Boydell Press A$51.91).

Back in the early nineties American author and critic Ken Mandelbaum wrote Not Since Carrie, a book which looked at 40 years of Broadway musical flops. Now the British musical theatre has received the same attention from Adrian Wright, a noted historian, whose previous tomes have included A Tanner’s Worth of Tune (2010) and West End Broadway (2012).

Must Close Saturday looks at West End musical flops with original scores between 1960 and 2016 and arbitrarily uses anything that ran less than 250 performances as the designation of what constitutes a flop. Wright lovingly and caustically documents the failure of 162 productions, stretching from The Lily White Boys to Mrs Henderson Presents.

The subjects in themselves make an interesting read - the electric chair, The Holocaust, Jack the Ripper, Edward and Mrs Simpson, the Virgin Mary, Barnardo’s orphanages, the match girls at the Bryant and May factory, Dr Crippen, Lewis Carroll and Marilyn Monroe to name a few.

And what do we learn? Like Broadway with Kelly (1965), London also had its own opening and closing in one night production. It was Oscar Wilde (2004), written by disc-jockey and pop-song writer Mike Read, which had the imprimatur of Wilde’s grandson, and had the Sunday Telegraph claiming it was “a musical of exquisite awfulness”. Set in 1895, when Wilde left England for France, he departed to the strains of “La Vie En Rose”, a song that was written in 1945. It lost eighty thousand pounds.

Cryogenics was the subject of Kingdom Coming (1973), another “car-crash” of a musical whose plot “involved characters being stuffed into refrigerators” and ran for 14 performances, whilst the vanity production Murderous Instincts (1973), “a hit in 2002 in Puerto Rico”, suffered a major blow when the director, Mickey Rooney’s son, was barred by Equity forcing him into continuing to direct the show by phone from Paris.

The book also shows no famous composer or lyricist is immune from a flop. Lionel Bart had his with his Robin Hood saga Twang!! (1965), a financial fiasco which saw him pouring four thousand pounds of his own money weekly into keeping the show running (it sent him bankrupt); Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jeeves (1975) had the shortest run of any of his works, playing just 38 performances; whilst his ex-lyricist partner Tim Rice floundered with an adaptation of James Jones’ Pearl Harbour attack, From Here to Eternity (2013), ironically at the same time Lloyd Webber was also struggling with his Profumo scandal musical Stephen Ward (2013).

Julian Slade and Dorothy Reynolds’ 2,283 performance success in the fifties with Salad Days (1954) did not translate into success in the sixties when Hooray for Daisy (1960) and Wildest Dreams (1961) only ran 51 and 76 performances respectively. Likewise, Sandy Wilson’s follow up to his 2,084 performance long-runner The Boy Friend (1953), set in the thirties where the characters are ten years older, Divorce Me Darling (1965), could only manage a dismal 87 performances.

According to Wright, David Heneker’s Jorrocks (1966), a flop at 181 performances, had a much stronger score than either of his long-runners, Half a Sixpence (1963) or Charlie Girl (1965).

Broadway greats were just as susceptible to the vagaries of London audiences. Charles Strouse and Lee Adams’ Queen Victoria epic, I and Albert (1972), hung around for 120 performances and was directed by film-maker John Schlesinger, who had never directed for the stage and had no previous experience with musicals. Jean Seberg (1983) had a score by Marvin Hamlisch, was produced by the National Theatre and was called “amateurish” by the press, whilst Stephen Schwartz’ Children of Eden (1991), based on the Book of Genesis, expired after 103 performances.

Australian performers abound - June Bronhill, Kevin Colson, Simon Gleeson, Philip Quast, Caroline O’Connor, Simon Burke and Helen Dallimore, with several musicals by Australian composers also discussed; Jason Sprague’s Edward and Mrs Simpson musical Always (1997), Ron Grainer’s bio of music-hall artiste Marie Lloyd, Sing a Rude Song (1970), with Barbara Windsor as Lloyd and Barry Gibb as one of her husbands, and my own Prisoner Cell Block H – The Musical (1995), based on the popular TV series which, on-stage, starred drag-queen Lily Savage.

In a book about flops it almost seems perverse to criticize someone for taking the popular path, but that’s what Wright does with author Wolf Mankowitz, whose career he believes, following the groundbreaking Expresso Bongo and Make Me An Offer, “diverted into sheer commercialism” with Pickwick.

Barely mentioning him in his previous book, A Tanner’s Worth of Tune, this time around Leslie Bricusse receives the full brunt of Wright’s scorn, especially for Kings and Clowns (1978), a musical about Henry VIII. He accuses him of going on a rhyming bender: “shrewder, lewder, wooed her, viewed her, pursued her, chewed her, ruder, cruder, shooed her, booed her, and poo-pooed her, but is it any worse than Sondheim’s “We’ve no time to sit and dither, while her withers wither with her” in Into the Woods.

Pithy reviews are the nature of the beast and Wright has assembled some quotable examples. Of 2005’s Beyond the Iron Mask, a musical by John Robinson about the 17th Century’s Eustache Daugher, imprisoned in the Bastille and elsewhere for 34 years, the Daily Express opined, “To suggest it is plain terrible does not do justice to its sheer gothic, relentless awfulness” or Charles Spencer’s review of Beautiful and Damned, a showabout F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, with songs by Roger Cook and Les Reed, “Reach for the sick bag or the bottle” and then went on likening Zelda to a “pushy assistant behind the cosmetics counter in Boots.” The Independent on Sunday was no different, “disappointingly witless. Pretty damned awful.”

Wright claims the book is “intended as a celebration, not a wake, but at times he comes dangerously close to the latter. No jukebox or rock musicals are considered, yet bewilderingly he includes, and tears apart, a songbook show about Lionel Bart’s life, Lionel (1977), which in concept follows a similar trajectory to Peter Allen’s The Boy From Oz. He also comments on three operetta revivals - The Dancing Years, Glamorous Night and The Maid of the Mountains - and it’s hard to see why they are included.

Like his other books, Wright is opinionated. He abhors Cockney knees-up songs unless they were written by Lionel Bart, who he believes is the only English composer who can write them with authenticity.

He tends to laud Broadway and its writers, yet skimming through the pages of Not Since Carrie it’s perfectly obvious they have had as many disasters as their English counterparts. Of course a book like this is subjective. Of the shows that didn’t make the 250 performance cut-off number, there are many I have personally enjoyed; Belle or the Ballad of Dr Crippen, Monty Norman’s music-hall musical, was fun with a nice blousy performance by Rose Hill, as was Cameron Mackintosh’s Moby Dick, whose central character (a precursor to Matilda’s Miss Trunchball) was a headmistress in drag (Tony Monopoly), which played like an end-of-year romp. I also liked Michel Legrand’s Marguerite, set during the Second World War but loosely based on Dumas’ La Dame aux Camelias, with great performances by Ruthie Henshall and Julian Ovenden.

Wright’s prose is easy and it’s authoritative. It’s a useful book to dip into, a must on the bookshelf of any serious musical theatre geek, and a great reference work. It comes with B&W photographs, an appendix, an index of musical works and a general index.

Note: Wright owns Must Close Saturday Records and has reissued several of the original cast recordings mentioned in the book on CD. Stage Door Records have also issued three CDs, Lost West End 1 & 2, and Lost West End Vintage, which include tracks from many of the flop musicals.

Something Wonderful – Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway Revolution by Todd S. Purdum (Henry Holt U.S.$32.00)

Something Wonderful – Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Broadway Revolution by Todd S. Purdum (Henry Holt U.S.$32.00)

Before Andrew Lloyd Webber and Stephen Sondheim, the musical theatre was dominated by the team of Rodgers and Hammerstein. The two middle-aged men had major careers before they worked together, but their pairing with 1943’s Oklahoma! saw them reinvent the genre, reverberating through the form to this present day. They created the ‘musical play’, which saw them integrate music, lyrics, dance and book in some of the most innovative musicals of the era. Their musicals became part of what is commonly called the “Golden Age” of Broadway.

So many books have been written before about their partnership, you have to wonder if there’s anything new to say. Not really, but veteran political reporter Todd S. Purdum does a very good job of offering a new perspective on their work, whilst uncovering the occasional nugget. The overriding aspect to emerge is that despite working together professionally for 17 years, the two men never really knew each other on a personal level.

Their coupling came at a critical point in both their careers; Hammerstein, after early success in the twenties with The Desert Song, Sunny and the groundbreaking Show Boat, had had a string of failures in the thirties, and Rodgers, following success after success with On Your Toes, Jumbo, Babes in Arms and Pal Joey, was finding it continually harder to work with lyricist Lorenz Hart, whose alcoholic binges kept getting longer and more destructive.

Into the mix came the Theatre Guild with the offer to make a musical of Green Grow the Lilacs, their unsuccessful 1931 folk play written by gay cowboy turned poet and playwright (Rollie) Lynn Riggs. Hart wasn’t interested but Hammerstein was, and so began Rodgers and Hammerstein, or as they came to be known R&H, the most influential composer and lyricist team of the modern musical theatre.

Purdum begins their story when they were at the height of their success in 1957 with the telecast of Cinderella, their only original musical written for TV, which starred the young Julie Andrews (moonlighting from My Fair Lady) in the title role, with Jon Cypher (who would go onto fame as Chief of Police Fletcher Daniels in Hill Street Blues) as the Prince.

Filmed in New York at Studio 72, a former Keith-Albee-Orpheum vaudeville house, the production was seen by 107 million people at a time when the entire U.S. population was roughly 172 million. More people collectively watched Cinderella than any event in the history of the medium.

Two brisk chapters about their early careers follow, before we get to Oklahoma! - which, in its day, according to Perdum, “was as radical in its way as Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip-hop, genre-bending Hamilton would be more than seventy years later.” Originally called Away We Go, their adaptation eschewed the typical musical comedy conventions of the day, dispensing with an opening chorus and creating the American theatre’s first fully realized psychological dance piece with the ballet Laurie Makes Up Her Mind. These ballets were to become a feature of their work. They also created the soliloquy “Lonely Room” for the character of Jud Fry, an angry resentful farmhand with a collection of dirty postcards who, in another first for a musical, is killed by the leading man. Rodgers’ daughter Mary said it was her favourite amongst her father’s nine-hundred plus songs.

Innovation continued with their next musical Carousel, which was based on Ferenc Molnar’s Liliom and depicted spousal abuse. The “If I Loved You” bench scene has become justifiably famous for its brilliant melding of dialogue and song, whilst the seven minute “Soliloquy” has become a masterwork of musical stream of consciousness. The score also included the inspirational song that became a football club anthem, “You’ll Never Walk Alone”. When Mel Torme told Rodgers the song made him cry. Rodgers replied, “It’s supposed to.” It was Rodgers’ favourite score.

Rodgers and Hammerstein followed with their most experimental work, the flawed Allegro, which became Broadway’s first “concept musical”. Inspired by Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, it was deliberately minimalist and set in small-town America in a simpler time. Running 315 performances it was the first, but not the last, flop for the duo. A 17-year-old Stephen Sondheim was employed on the production during his summer break as a gofer. It was his first job in the theatre.

R&H continued to expand the boundaries of musical theatre with South Pacific, and its themes of racial discrimination, bigotry and prejudice, then followed with cultural and societal differences in Siam with The King and I, and later explored similar Asian themes on home soil in San Francisco’s Chinatown in Flower Drum Song.

The early fifties saw them produce their most undistinguished work, the backstage musical Me and Juliet, which ran 358 performances and has never been revived, and a musical adaptation of John Steinbeck’s brothel-set Sweet Thursday, which became Pipe Dream and only managed to run 246 performances.

Their last most enduring work, but also their most reviled was The Sound of Music, the story of the Von Trapp Family Singers and their escape from Austria over the Alps in the lead up to the Second World War. Called an operetta by the critics, Walter Kerr (Herald Tribune) complained that “the revolution of the forties and fifties had lost its fire.” Rodgers and Hammerstein were now labelled old-fashioned and out of step, and although it would go on to become one of the highest grossing musical films of all time, starring Julie Andrews, for Rodgers and Hammerstein the first night reaction was bitter-sweet.

Hammerstein died shortly after The Sound of Music opened, while Rodgers succumbed to cancer twenty years later, but lived “long enough to see his own best work recognised as immortal.”

Both men had their demons. Rodgers suffered from bouts of depression and became an alcoholic - someone who could down 16 whiskys after dinner and not show the effects. He was also a notorious womaniser and kept a room in a Times Square hotel for his assignations. Hammerstein was plagued by the fact that he was seen as a has-been operetta lyricist. Sentimental and lovable, he has always been portrayed as a family man, yet even he succumbed to adultery with showgirl Temple Texas during Pipe Dream. Rodgers was aware of it but it is unclear whether his wife knew.

Both men were married to women called Dorothy, who were both interior decorators but with totally different tastes. Dorothy Rodgers came from affluence and, according to her daughter Mary, was “uptight, anorexic, and a chronic abuser of laxatives and Demerol.” Dorothy Hammerstein was a chorus-girl who came from Tasmania. Hammerstein wrote some lyrics for Allegro and Cinderella while he was visiting his in-laws.

According to Purdum both men were keen businessmen, but “chary with collaborators, stingy with credit, and notoriously tight with a buck.” Costume designer Lucinda Ballard claimed, “Dick loved money more than anybody I’ve ever seen, except Oscar.” Joshua Logan wrote 30-50% of South Pacific’s book yet R&H refused him any royalties except those he received for direction. It galled him until the day he died.

Lyrics for “Someone Will Teach You”, an early draft version of “People Will Say We’re In Love”, are interesting, as are early drafts for South Pacific’s “Happy Talk” and “Now Is The Time”, a song that was replaced by “This Nearly Was Mine”.

Orchestrator Robert Russell Bennett, arranger Trude Rittman and choreographer Agnes de Mille receive due credit in Purdum’s analysis of R&H’s success, but it’s a de Mille bombshell that startles. In an unpublished monograph written late in her life, she insisted (with the inferred backing of Rittman) that Rodgers lifted The Sound of Music’s “Praeludium” from a work by Orlando de Lasso, a sixteenth-century Franco-Flemish composer, and claimed it as his own.

This well-researched book ends with Nicholas Hytner’s re-examined Carousel for London’s National Theatre in 1992, which kick-started a wave of reassessment of their body of work.

Something Wonderful is truly a wonderful read, which offers insight into the creation of some of the most enduring musical theatre classics ever written. It comes with B&W photos, notes, and an index. Highly recommended

The Ballad Of John Latouche – An American Lyricist’s Life and Work by Howard Pollack (Oxford University Press U.S.$39.95)

The Ballad Of John Latouche – An American Lyricist’s Life and Work by Howard Pollack (Oxford University Press U.S.$39.95)

When people talk of John Latouche, if they talk of him at all today, they’re apt to call him a forgotten, unsung or little-known lyricist, yet for a time he was one of the most active and versatile creators working on Broadway. During his short life (he died at 42), he managed to cram in an amazing career that encompassed not only Broadway and cabaret, but also, radio, poetry and film. The wit and skill of his lyrics was likened to Lorenz Hart, Ira Gershwin and Cole Porter, whilst his celebrated list of friends read like a who’s who, with everyone from Truman Capote and Carol Channing, to Tennessee Williams, Salvatore Dali and Marlene Diedrich.

Duke Ellington, with whom he wrote an interracial version of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera titled Beggar’s Holiday (1946), called him “a great American genius”, whilst Stephen Sondheim said in his quest to develop a lyric theatre that combined music, word, dance, costumes and art direction, “he had a large vision of what musical theatre could be.” His most popular song was ‘Taking a Chance on Love’, written with frequent collaborator Vernon Duke, and came from the Broadway musical Cabin in the Sky (1940), whilst his highest profile lyric credit was for Leonard Bernstein’s Candide (1956), written the year he died.

Latouche was born in Baltimore in 1914 but raised in Richmond, Virginia, where he attended the John Marshall High School. His mother was Jewish, but he claimed he was protestant by conviction. According to Pollack, theatre helped alleviate “the poverty, rootlessness, abuse, alcoholism and psychosis that plagued his family.”

A $1,000 scholarship enabled him to relocate to New York and enrol in Columbia University. He won some minor awards for his poetry and prose, but collegiate shows revealed his forte to be song lyrics. He contributed some lyrics to the left-leaning revue Pins and Needles (1937) before gaining national success with Ballad for Americans, a 10-minute folk-opera cantata written with Earl Robinson, that was featured in the Federal Theatre Project revue, Sing for Your Supper (1939). Extolling the virtues of democracy and liberty through the voice of an everyman figure, it was recorded by African-American baritone Paul Robeson, and the most popular singer of the day, Bing Crosby. Its appeal was so broad-ranging that it was sung at conventions of both the Republican Party and the American Communist Party.

Latouche followed Cabin in the Sky with the Eddie Cantor vehicle Banjo Eyes (1941), again written with Duke, which was a quick fold at 126 performances, before he found a particularly like-mined collaborator in Jerome Moross, with whom he wrote two of his most significant works: Ballet Ballads (1948) and The Golden Apple (1954).

Ballet Ballads was series of four dance-cantatas - Susanna and the Elders, which placed the biblical story of Susannah in the rural American Midwest; Riding Hood Revisited, a combination of Disney and a slightly lascivious version of the Little Red Riding Hood fairytale; Willie the Weeper, which depicted a poor chimney sweep’s fantasies of wealth, fame, power, and sex when high on marijuana, and The Eccentricities of Davy Crockett, which recounted the life of the fabled hero associated with America’s westward expansion.

Ballet Ballads opened Off-Broadway on May 9 but because of positive notices was quickly transferred to Broadway where, despite enormous goodwill concessions on behalf of the theatre owners and the cast, it expired on July 10.

Latouche’s other collaboration with Moross was the score treasured by show music buffs the world over, The Golden Apple, which also opened Off-Broadway to rave reviews, transferred to Broadway and suffered the same dismal fate of only surviving 174 performances. The sung-through piece was a retelling of theIlliad and The Odyssey in turn-of-the-century America. Frequently called “one of the American Theatre’s most beloved failures”, the score produced the standard ‘Lazy Afternoon’, which has been recorded by artists such as Tony Bennett and Barbra Streisand.

Two years later, still working in the folk story idiom, Latouche and composer Douglas Moore created The Ballad of Baby Doe (1956), about the scandalous romance of the Colorado silver mining magnate Horace Tabor, his great wealth gained and lost, and his eccentric femme fatale wife Baby Doe, who died frozen to death in a hut beside the silver mine. It opened to rave reviews and was ranked with Porgy and Bess and The Most Happy Fella as a “significant contribution to American opera” by John Chapman in the New York Daily News.

Although he’s still credited as co-lyricist, Latouche’s contribution to Leonard Bernstein’s comic-operetta Candide (1956), based on Voltaire’s satire,is slim indeed. Notoriously slow to deliver on his lyrical assignments, Bernstein became so exasperated he fired him after he’d only completed the first act. His replacement, also a poet, Richard Wilbur ended up revising almost all of Latouche’s work but Latouche still received a credit and royalties. In the intervening years, the show has undergone many transformations and the current version, authorised by Bernstein, has put back a lot of Latouche’s original work.

In the forties Latouche wrote the lyrics for two European operettas, Fritz Kreisler’s Rhapsody and the Chopin adapted Polonaise (1945), a second musical with Vernon Duke, The Lady Comes Across (1941), and The Vamp (1955), a musical about Hollywood’s silent-era for Carol Channing.

Like his contemporary Lorenz Hart, Latouche was more intent on partying until the dawn than writing lyrics. According to Pollack, “There were drinking binges, and he would disappear for days on end.” He smoked excessively, took all manner of drugs, and very rarely met a deadline. He was also promiscuous with both men and women, but mostly men, although he did marry Theodora Griffis in 1940 and they stayed married for five years.

Well-liked and a celebrated raconteur, his soirees attracted the crème-de-la-crème of the arts. His “little friends”, so named because of their short stature, were a group who comprised, amongst others, Virgil Thomson, Marc Blitzstein, Aaron Copland, Carson McCullers, and Australian composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks, who at one time became Latouche’s live-in help. He even helped her husband beat a male solicitation charge. Tennessee Williams met his long-time partner Frank Merlo at the soirees.

Latouche also attracted émigrés who were fleeing the Nazis and the war in Europe by the dozen. Although barely surviving himself on what little royalties he earned, he was always a willing ear, drinking buddy and bed-provider (sometimes partner) to these displaced musicians and artists.

Pollack’s claim that “Latouche was bridging a gap between high art and popular art” is very apt. In fact in his pushing of the boundaries of musical theatre he was a precursor to Sondheim. His lyrics had a rare sophistication and poetic sensibility, but the road to that sophistication was sometimes too difficult for his collaborators to negotiate. Kurt Weill once planned to write a show with him, but when Latouche turned up late and hung over, Weill threw up his hands and said, “I can’t work with him.”

Latouche’s death at an early age from a coronary occlusion sent shock waves through New York’s art scene. Playwright Carson McCullers summed up the reaction succinctly. “John was a man who died as he was approaching the peak of his greatness. We can only think with wonder and sorrow about the work he would have done.”

Pollack has done an incredible job of recreating Latouche’s career and his life. One has to admire his attention to detail, where full biographical notes are given even for the most obscure composer that Latouche worked with, together with an extensive scene by scene synopsis of the musicals he created. A rich biography and a compelling read, it comes with B&W glossy photographs, notes and an index.

Forever Horatio – An Actor’s Life – Edmund Pegge (Wakefield Press $39.95)

Forever Horatio – An Actor’s Life – Edmund Pegge (Wakefield Press $39.95)

The word that comes to mind after reading Edmund Pegge’s amiable biography Forever Horatio is that he was a survivor in a profession where actors are lucky if they get five minutes of fame. Pegge never got his, but in a fifty-year career, never seeing his name up in lights, he worked constantly as a second-stringer in film, television and theatre in the UK and Australia. Yes, he did have his down time, which was spent mostly landscape gardening and playing cricket, but he worked with some famous names and got to travel to exotic places courtesy of well-paid commercials.

Pegge was born in England in 1939 but spent his later school years in Adelaide before embarking on an acting career. He went to NIDA in the fifties, toured with the Young Elizabethan Players 1958-1964, and travelled to London in 1965, immediately finding work at Nottingham Playhouse. His fellow thespians in the company included Edward Woodward, Michael Craig and Judi Dench, who wrote the forward to this book.

Pegge later made brief appearances in Dr Who, The Bill and the movie Follow that Camel. He did tours of the US and Canada in plays by Shaw and Coward and played Travels with my Aunt to British ex-pats in Hong Kong, Bangkok and Singapore. His Australian TV credits include Father Murphy in ABC’s Home Sweet Home. Onstage he has played everything from Shakespeare to farce and in the nineties successfully took poetry readings, exploring Australian identity, to schools. He never married but had multiple girlfriends along the way.

It’s a pleasant read, full of choice anecdotes of a jobbing actor (like landladies in regional Britain providing suppers of sandwiches and cocoa after a show), and comes with B&W photos of family, school, fellow actors and in-performance stills.

The Sleeping Beauty – David McAllister & Gabriela Tylesova (Little Hare $29.99)

The Sleeping Beauty – David McAllister & Gabriela Tylesova (Little Hare $29.99)

The Australian Ballet’s much-loved and appreciated version of Tchaikovsky’s The Sleeping Beauty has been transferred to a picture book with a text by the Australian Ballet’s artistic director David McAllister and illustrations by Gabriela Tylesova, who created the ballet’s design. The result is an exquisite and handsome gold-foil covered picture book of hand-drawings of the ballet’s story, with a clear and concise text. All of the favourite characters are there from the Sleeping Princess and the Prince, to the Lilac Fairy and the evil Carabosse, stunningly drawn in beautiful pastel coloured line illustrations. It also includes photos from the stage production and is an ideal gift for balletomanes, the young, and the young at heart.

Close To The Flame – The Life of Stuart Challender by Richard Davis (Wakefield Press $45.00).

The publisher’s sub-title for this biography of Stuart Challender is “An extraordinary musical life cut too short”, which is an apt description of Challender, who was on the cusp of a major international career when he was struck down with AIDS.

Challender was one of the greatest conductors Australia has ever produced. Born in Hobart 19 February 1947, to a father (David) who was an AFL football champion and a mother (June) who played piano in her spare time, his love of music came from his grandmother Thelma Driscoll.

On reaching puberty, Challender discovered he was sexually attracted to other boys and the guilt of those feelings pervaded his life until he died. He attended an all boys school which yearly performed a Gilbert and Sullivan opera. On one of these occasions Challender played Peep-Bo in The Mikado. It’s ironic that in later years he professed to loath G&S and most English music except Elgar, who he revered.

In 1964, at 17, Challender studied piano under Ronald Farren Price at the Melbourne Conservatorium (to concert platform standard), and he was also proficient at clarinet, but conducting had been his passion since being taken by his father to see a production of Beethoven’s Pastoral conducted by Tibor Paul with the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra when he was young.

In Melbourne Challender set up the Melbourne Youth Chamber Orchestra and started to compose. Unfortunately no manuscripts survive of his original work. He also worked in a variety of roles with the then amateur Victorian Opera Company, where his first production was Britten’s Albert Herring.

His first professional conducting engagement was after he decamped to Europe in 1970 for Lucerne Opera, Switzerland, where he conducted Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate. He was appointed assistant conductor at the Staatstheater, Nuremberg, and he also worked for Zurich and Basel Opera where he conducted an acclaimed production of Mozart’s Die Zauberflote (The Magic Flute). He also conducted performances of Otello, La Traviata, Madama Butterfly, Carmen and Eugen Onegin. It was during this time he had a hetrosexual affair and lived with the vivacious dramatic soprano Marilyn Zschau, who became a lifelong friend.

Challender spent 12 years in Europe before returning to Australia, working for the Australian Opera before becoming principal conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra from 1987 to 1991. A production of Resurrection, Mahler’s second symphony, at the Sydney Town Hall with an augmented Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the Town Hall’s massive pipe-organ, the Sydney Philharmonia Choir, and soprano Valerie Hanlon and mezzo-soprano Elizabeth Campbell, was a landmark concert in the history of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Fred Blanks in the Sydney Morning Herald claimed it was “the best thing that Stuart Challender has done since his career began here.”

In the Bi-centennial year he led the orchestra in a successful 12-city tour of the United States, which culminated in a concert at the UN. In 1983 Challender was diagnosed as being HIV positive which developed into full-blown AIDS in 1987. His employers, the Australian Opera and the ABC, at first tried to keep it under wraps but eventually Challender decided to go public about his condition, at the time one of the first public figures in Australia to do so. Richard Davis does an excellent job of capturing the emotional toll on not only Challender but also those around him. The latter part of the book is extremely moving.

Challender died at 44. Apart from his legacy of achievements with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra he is remembered for his championing of Australian composition and composers; Nigel Butterley, Richard Meale and especially Carl Vine, amongst others. It was fitting therefore that a seven-minute solo cello piece by Peter Sculthorpe titled Threnody: In Memorium Stuart Challender was played at this funeral. The book comes with a chronology of his life and career, a discography, B&W photos and an index.

The Life and Times of Mickey Rooney by Richard A. Lertzman and William J. Birnes (Gallery Books U.S.$30.00)

The Life and Times of Mickey Rooney by Richard A. Lertzman and William J. Birnes (Gallery Books U.S.$30.00)

When Mickey Rooney died aged 93 in 2014 Vanity Fair called him “the original Hollywood train wreck”; an actor who during his peak years, from the late 1930s to the early 1940s, was the top box-office attraction in the United States, an actor who kept MGM afloat, and an actor Laurence Olivier said “was the greatest actor America ever produced.”

Rooney, who married eight times, made millions and lost millions at the racetrack or the poker table. One of his favourite lines was “I lost two dollars at Santa Anita and spent three million trying to get it back.” The other was, “Always get married in the morning. If it doesn’t work out you haven’t wasted the whole day.”

Rooney was born in a trunk. His father Joe Yule came from Glasgow, Scotland, while his mother Nellie Carter was a chorus girl. They both worked in burlesque, and it was there Rooney had his first taste of the spotlight when he started performing on stage at one and a half years of age singing “Pal of my Cradle Days”.

Audiences loved him and it wasn’t long before Nell (sans husband Joe) was getting Rooney auditions in Hollywood’s burgeoning film business. From 1927 until 1936 he made 78 short comedy movies about pint-sized Mickey McGuire. This led to him becoming a contract player at MGM.

In 1937 Rooney was selected to appear as Andy Hardy in the B movie A Family Affair, with a story idea which sprang from the movie success of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness! A Family Affair’svision of small-town Americanawas an unprecedented success which resulted in the company making 13 more in the series. In three of them Rooney starred opposite Judy Garland and together they became a successful song-and-dance team, making several musicals including Rodgers and Hart’s Babes in Arms. He also hit it big with a straight role in Boys Town alongside Spencer Tracy, rumoured to be MGM boss Louis Mayer’s favourite film.

During the forties Rooney saw active service entertaining troops in Europe but on his discharge, as a 5ft 2in adult actor, his career went into decline. During the sixties he returned to the stage and toured as Pseudolous in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and as the title character in George M.

Dinner theatre paid the bills during the seventies until he had phenomenal success on Broadway starring opposite his former MGM colleague Ann Miller in Sugar Babies. The show was a salute to burlesque and Rooney was in his element. The critics and audiences adored him. He played 1,208 performances on Broadway (never missing one) and then toured with it for five years, which included eight months in London. He was paid $17,000 per-week and over the entire run earned $40 million dollars, but it all disappeared on gambling debts, alimony, family support, and taxes.

His first marriage was to 19-year old Ava Gardner. It lasted one year. Next came Betty Jane Rase, who bore him two sons, Mickey Jnr and Tim. Wife number four provided him with a son, Jimmy, and daughter, Jonelle, while marriage number five, with Barbara Ann Thomason, produced Michael Joseph Rooney. He had his longest relationship (34 years) with his eighth wife Jan Chamberlin. Rooney was a loving husband but he got bored easily with marriage and always returned to his former ways, carousing and partying and bedding a different starlet each night. He was also an absentee father and never really knew his off-spring. The murder/suicide of his fifth wife Barbara Ann and her secret lover took its emotional toll on Rooney and it took him a long time to recover from it.

In his nineties Rooney was outspoken about elder abuse, claiming he was a victim of it and appeared before a special U.S. Senate committee that was considering legislation to curb it.

This book is tabloid journalism at its worst, scraping the bottom of the sleaze barrier time and time again. If there’s a sordid or lascivious anecdote that Birnes and Lertzman have uncovered then it’s in here. The editors must have been on holiday because it’s also full of spelling errors, mistakes and stories that are repeated. Rooney deserves better. It comes with a filmography, credits, B&W photos and index.