Stage to Page - 2015

In each edition of Stage Whispers magazine, Peter Pinne reviews the latest theatrical books. We've collated Peter's book reviews from 2015.

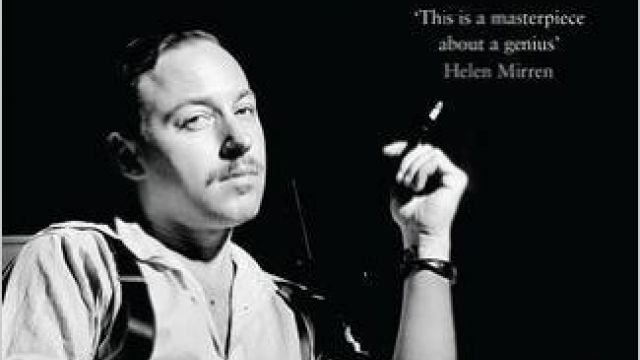

Tennessee Williams – Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh by John Lahr (Bloomsbury Circus $49.99).

Has there ever been a better theatrical biographer than John Lahr? I doubt it. After writing award-winning books on Joe Orton (Prick Up Your Ears), andBarry Humphries (Dame Edna Everage and the Rise of Western Civilisation: Backstage with Barry Humphries), he now turns his attention to one of America’s greatest playwrights, Tennessee Williams. According to Lahr there have been over 40 books written about Williams, but this new volume is undoubtedly the gold standard. It’s been short-listed for the National Book Award and deservedly so because there has never been a better book about Williams, his life and his career.

Between 1945 and 1961 Williams was the playwriting giant of Broadway. Beginning with The Glass Menagerie in 1945, a play that received 24 curtain calls on its opening night, Williams went on to write A Streetcar Named Desire, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Summer and Smoke, Suddenly Last Summer, The Rose Tattoo, Sweet Bird of Youth, Orpheus Descending and Night of the Iguana, and worked with some of the greatest post-war actors of his generation; Marlon Brando, Paul Newman, Geraldine Page, Anna Magnani, Maureen Stapleton, Eli Wallach and Ben Gazzara.His plays won the Pulitzer Prize twice and the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award four times. His partnership with director Elia Kazan was called “the most influential in 20th century American theatre.”

Eugene O’Neill freed American drama from its puritan corset, and Williams took it a step further with his mix of poetic imagery, melodramatic excess and Southern Gothic brutality. Once Williams got his foot in the door American drama was to never be the same again. His larger-than-life characters became part of American folklore; Amanda Wingfield, Blanche DuBois, Stanley Kowalski, Big Daddy, Maggie, Brick and Laura all transcended their stories and their dialogue became almost ‘anthems in the national imagination’, i.e. “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers” from A Streetcar Named Desire.

Williams’ family DNA is all over his work. With a repressed mother who eschewed alcohol and sex as much as possible and a father who loved both, the family home was a constant battlefield. His mother Edwina became the model for Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie and his bullying, alcoholic father CC (Cornelius Coffin) was unmistakeably Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Edwina was so repressed about sex and sexuality, that when her daughter Rose, still a virgin, fantasised about abusing herself with altar candles, Edwina had her lobotomised to shut her up. This act had a lasting effect on Williams who lived with the guilt of not doing enough to stop it all of his life.

His other lifelong guilt was his homosexuality (his father’s nickname for him was “Miss Nancy”). Williams was a late bloomer, but when he discovered the joys of the flesh he was fervently promiscuous. He claimed his two loves were writing and sex and his appetite for both was voracious. The two great lovers in his life were both Latin; Mexican, Pancho Rodriguez, and Italian, Frank Merlo. His passionate and tempestuous affairs with both all ended up in some form or other on stage. When Pancho arrived home drunk one night in Key West, Williams refused to answer the door. Pancho eventually found his keys and upon entering proceeded to break all the light bulbs in the house. The incident ended up in Streetcar.

Lahr’s account of Bette Davis’ antics in the original Broadway production of Iguana, and the closed-out-of-town David Merrick revival production of The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore with Tallulah Bankhead and Tab Hunter take theatrical bad-behaviour to a new level. Although his later work, written when he was heavily under the addiction of alcohol and prescription drugs, fell out of favour with the public and the critics, Lahr believes Small Craft Warnings and A House Not Meant To Stand are equal to many of his classics.

Williams’ closest female friends were his agent Audrey Wood, who Williams eventually fell out with after three decades, and “occasional actress” Lady Maria St Just (nee Britneva), who lived a fantasy where she believed Williams would marry her. It was never going to happen. But she was very persuasive and got him to make her literary executor of his work, which after his death proved disastrous. The wilful and devious St Just, piqued at Williams for only mentioning her 11 times in his book Memoirs, bullied the librarians at Harry Ransom Center, Austin, to leave her alone with Williams’ letters whereby she took a razor blade and cut out any derogatory references to herself, unaware that copies were preserved on microfilm.

Lahr’s sources for this magnificent appraisal of Williams’ oeuvre were diaries, letters, poems, and interviews with professional and personal friends. Each play and its production are meticulously researched while the use of Williams’ poetry excerpts to illustrate the content is masterful.

The Nick Enright Songbook - Edited by Peter Wyllie Johnston (Currency Press $49.95)

The Nick Enright Songbook - Edited by Peter Wyllie Johnston (Currency Press $49.95)

The publishing of Australian musical scores is rare, and the publishing of any individual songs from them even rarer, so this collection is a welcome and worthy addition to any music library. It contains 50 songs from ten musicals with lyrics by Nick Enright. They also represent the work of five different composers; Terence Clarke, David King, Max Lambert, Alan John and Glenn Henrich, whose music is published in print form for the first time.

The album of songs covers a 24 year period, from Enright and Clarke’s hit Aussie version of Goldoni’s play The Venetian Twins in 1979 to Enright and King’s account of the life and times of boxer Les Darcy in The Good Fight in 2002. In between came the chamber musical Variations which won the 1983 New South Wales Premier’s Literary Award for Drama, the depression-era On the Wallaby (1978), the travelling show-folk salute Summer Rain (1983), a televangelist expose, Miracle City (1996), the epic convict story of Mary Bryant (1996), plus Buckley’s! (1981) and The Betrothed (1993).

Peter Wyllie Johnston’s “An Appreciation” at the beginning of the book gives an authoritative overview of Enright’s career in which he claims Enright was “the most experienced professional Australian lyricist of his generation and the most influential” and this volume of literate and eclectic material justifies his claim.

Johnston also writes at length about the history and performance of each production. Of particular interest is the saga of Orlando Rourke (1985), a musical about Australia’s early film industry mounted by the State Theatre Company of South Australia, which was cancelled in rehearsal. Enright’s dedication to the musical genre was rewarded when he posthumously received a Tony Award nomination (with Martin Sherman) for his book for the jukebox musical The Boy From Oz (2003) following the Broadway run.It was a fitting tribute to a short but illustrious career and this songbook is a fitting and lasting legacy. Songs include “Jindyworoback”, “Once In a Blue Moon”, “Sail Away” and “I’ll Hold On”.

Olivier by Philip Ziegler (MacLehose $49.00).

Olivier by Philip Ziegler (MacLehose $49.00).

“I couldn’t believe anyone as good-looking as that could be such a rivetingly good actor,” said John Mills to Noël Coward about Laurence Olivier’s performance in the original production of Coward’s Private Lives. Jane Lapotaire recalls how, when playing the minor part of the butler in Feydeau’s farce A Flea in her Ear, he turned “a play about a woman who thinks her husband is unfaithful to her” into “a play about a butler who works for a woman who thinks her husband is unfaithful to her”. Anecdotes like these abound in Philip Ziegler’s book Olivier, which was short-listed for the Sheridan Morley Prize for theatrical biography in 2014.

Although there have been over 40 books written about Olivier, what sets Ziegler’s apart is him having access to long-time literary editor of The Spectator Mark Amory’s over 50 hours of tapes recorded in 1979 for a book he was commissioned to ghost write for Olivier, but which Olivier ended up writing himself.

Frequently called “the greatest stage actor of the twentieth century”, the charismatic, earthy and outspoken Olivier succeeded beyond his wildest dreams, becoming the first member of the acting profession to be made a peer. When he died on 11 July 1989, St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey vied for the right to conduct the burial service. The Abbey won and he is buried there alongside theatre immortals David Garrick and Henry Irving, and beneath the bust of Shakespeare.

Olivier was born 27 May 1907 to a prep-school father, who opened his own school before becoming a minister. Olivier’s mother secured a place for him in a minor public school where he played Brutus in Julius Caesar and Kate in The Taming of the Shrew. A very young Sybil Thorndike described his performance in the latter as “wonderful – a bad tempered little bitch”. He spent two years at Birmingham Rep where he acted alongside Peggy Ashcroft and Ralph Richardson. He played Uncle Vanya at 20. By the mid-30s he had tackled six major Shakespearian roles at the Old Vic in eight months. Olivier’s sexual appetite was voracious. He seduced almost every woman he came in contact with and it continued throughout his three marriages, and, despite ill-health, into his 70s. It was frequently rumoured that he was bi-sexual and had affairs with Marlon Brando and Danny Kaye, but Ziegler refutes these claims. He was married three times, all to actresses; his first marriage was to Jill Esmond, who later turned out to be lesbian, his second, and probably his one true love was to the bi-polar Gone with the Wind star Vivien Leigh, and his third was to Joan Plowright.

Olivier became a Hollywood star in the 1930s in Wuthering Heights, Pride and Prejudice and Alfred Hitchcock’s first movie version of Rebecca. Following the success of his 1945 film adaptation of Henry V (Olivier received a special Academy Award for his outstanding achievement as actor, producer and director in bringing Henry V to the screen), he made two more Shakespearian film adaptations; Hamlet and Richard III, which were both highly acclaimed. Later movies included The Boys from Brazil, Sleuth, Marathon Man, Spartacus and The Prince and the Showgirl with Marilyn Monroe. He also made memorable movies of his stage performances in Long Days Journey into Night and as Archie Rice in The Entertainer.

Olivier and Leigh were treated like royalty when they toured Australasia with the Old Vic at the height of their popularity in 1948. The tour included R.B. Sheridan’s School for Scandal with Leigh as Lady Teazle and Olivier as Sir Peter, Richard III, which London had seen in 1944, and Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of our Teeth with Leigh as Sabina the maid and Olivier as Antrobus. The tour was hugely successful, playing to over 300,000 people and grossing £226,318.

Probably Olivier’s greatest achievement establishing Britain’s National Theatre in 1963, which he ran until his retirement due to iIl-health. During his tenure he employed as dramaturge the enfant terrible Kenneth Tynan, a disciple of the new kitchen sink drama, who had established a brutal reputation as a critic for The Observer. Tynan’s appointment was controversial, and in Ziegler’s portrayal of the scenario, Olivier’s Judas/Iago.

Throughout his life Olivier was an obsessive exercise freak and insanely jealous, especially of any actor who looked like they might be a rival. He was also poetically foul-mouthed. His final appearance on stage was as a holograph at the finale of the Cliff Richard musical Time in 1986. Olivier became a legend and remains one to this day. Ziegler’s tome, and it is pretty hefty at 460 pages, is a highly readable account of one of the acting profession’s greatest practitioners. It comes with a comprehensive index, source notes and black and white photographs.

Yes, Miss Gibson – The life and times of an Australian radio legendby James Aitchison & Reg James (Vivid Publishing $29.95).

Yes, Miss Gibson – The life and times of an Australian radio legendby James Aitchison & Reg James (Vivid Publishing $29.95).

Considering it was the main source of income for many Australian actors, very few books have been written about the hey-day of Australia’s radio industry in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. This informative volume by James Aitchison and radio pioneer Reg James goes some way towards redressing the situation in its appraisal of one of the pioneers of the industry.

Grace Gibson was born in 1905 in El Paso, Texas, to a rancher and taxi driver father who was a card-carrying member of the Klu Klux Klan, and a Mexican mother. She started working in radio in Hollywood selling radio programs and arrived in Sydney in 1933 to do the same thing.

She soon became the highest paid woman working in pre-war radio in Australia. Frank Packer was an early influence and supporter. In 1944 she married Ronnie Parr and immediately set up her own production company, Grace Gibson Productions.

Gibson had the Midas touch and was soon producing more radio drama than any other production house in the country. Some of her most successful titles were Dossier on Demetrius, Dr. Paul, Portia Faces Life, Night Beat, Address Unknown and Deadly Nightshade, and the blue chip actors she worked with included Peter Finch, Rod Taylor, Michael Pate, Alastair Duncan and Dinah Shearing. But although radio drama lost its dominance when television arrived, Gibson continued to produce, creating her most successful series, Castlereagh Line, in 1982.

The authors both worked for Gibson; James started as a despatch boy and became a sales manager, Aitchison was a writer. The book lovingly documents Gibson’s achievements, notable in an industry dominated by men. The company still continues today, re-packaging some of its greatest hits for global consumption. It’s nice to know that somebody somewhere in the world is still listening to Dossier on Demetrius. Eight pages of B&W photos accompany the text.

West End Broadway - The Golden Age of the American Musical In London by Adrian Wright (Boydell Press US$45.00).

West End Broadway - The Golden Age of the American Musical In London by Adrian Wright (Boydell Press US$45.00).

Life in post-war Britain was austere - rationing was still in place, newspapers were restricted to a maximum of four pages, foreign holidays were illegal, and in an effort to save coal the government cut train services by 10%. But the theatre, and in particular the musical theatre, was thriving thanks to a “fresh breeze” blowing across the Atlantic from America.

This is the historical background that informs Adrian Wright’s portrait of the impact the iconic Broadway musicals had on London theatre of the period. From Oklahoma! and Annie Get Your Gun, through West Side Story and Funny Girl, to Promises, Promises and Company, Wright discusses, dissects, and re-evaluates every Broadway, and some Off-Broadway, musicals that opened in London between 1945 and 1972. It’s authoritative, comprehensive, and not selective.

It was a period when important works by Leonard Bernstein, Comden and Green, Lerner and Loewe, Frank Loesser, Harold Rome and Sondheim were introduced to the West End, and also saw the importation of many American actors, some who were already stars; Barbra Streisand, Lauren Bacall, Mary Martin and Chita Rivera, and some who became stars in Britain; Howard Keel, Dolores Gray and Julie Wilson. It also saw the rise of many British artists to above-the-title status; Pat Kirkwood, Jean Carson, Edmund Hockridge and Millicent Martin to name a few. Australian names abound; June Bronhill, Maggie Fitzgibbon, Joy Nichols, Keith Michell and Lewis Fiander.

Not all of the Broadway successes translated into West End hits, and in some cases a Broadway also-ran like Paint Your Wagon did much better in its London outing, as did Sail Away, West Side Story and The Sound of Music. The flops, like the 1960s obscurity The Dancing Heiress are just as interesting as the hits.

Wright’s prose is clear and elegant, and the book comes with a more-than-useful appendix, which lists casts, songs and creative personnel for every show, plus an index and photos.

You Fascinate Me So – The Life and Times of Cy Coleman by Andy Propst (Applause US$32.99).

You Fascinate Me So – The Life and Times of Cy Coleman by Andy Propst (Applause US$32.99).

Clear and elegant prose is what sets Andy Propst’s biography of Cy Coleman’s life apart from other composer biographies. By concentrating on his career, with scant details of his private life except his late-in-life marriage, Propst documents the turbulent ups and downs of Coleman’s Broadway musical history from Wildcat in 1960 to The Life in 1997. An almost 40-year fertile period saw him create Little Me, Seesaw, Barnum, On The Twentieth Century, I Love My Wife, City of Angels, The Will Rogers Follies, and the musical he’s most remembered for Sweet Charity.

Progressing from child prodigy giving recitals at five in the thirties, to jazz pianist in the forties, and to writing hits for Frank Sinatra in the fifties (“Witchcraft”), Coleman’s jazz background influenced his scores from the beginning, bringing something fresh to the Broadway palette. He worked with many lyricists, but had his greatest successes with Carolyn Leigh and Dorothy Fields, whose smart wordplay seemed the perfect fit for Coleman’s intricate tunes.

It’s a first-ever biography of the composer, which uncovers details about projects that never got off the ground, and those that lasted only a few performances.

Coleman was already a TV and cabaret-room celebrity when he began writing for Off-Broadway intimate revue in the 50s (John Murray Anderson’s Almanac/Demi-Dozen), and he frequently returned to play cabaret boites throughout his career.

At 983 performances 1991s The Will Rogers Follies was his longest running Broadway show. With eleven produced musicals to his credit, Coleman was one of the greats of Broadway and Propst’s book lovingly salutes his achievements. The book comes with a detailed index and professional and private photos, plus sheet music and record covers.

Double Act – The remarkable lives and careers of Googie Withers and John McCallum by Brian McFarlane (Monash University Publishing $39.95).

Double Act – The remarkable lives and careers of Googie Withers and John McCallum by Brian McFarlane (Monash University Publishing $39.95).

Googie Withers and John McCallum were Australian theatre royalty. During the 50s and 60s their partnership on stage guaranteed full-houses for J.C. Williamson in every play they appeared in. Brian McFarlane documents their enduring partnership and marriage of 62 years, and how they ascended to their star status in English movies.

Withers was born in India and spent her early career making second-feature movies with occasional appearances on stage. McCallum was born in Australia to theatrical parents and after AIF duty in the Second World War played opposite Gladys Moncrieff in musical revivals of Maid of the Mountains and Rio Rita. They met in 1947 when they were starred together in the movie The Loves of Joanna Godden, and followed it with an even bigger success It Always Rains on Sundays the same year.

Both were incredibly active on the West End stage in the 50s in Shakespeare, Shaw, Odets and Rattigan, but drawing-room comedy was their forte. They first toured Australia in Alan Melville’s Simon and Laura romp and from then on their coupling was assured with local audiences. They settled permanently in Australia in 1958 when McCallum became Joint Managing Director of J.C. Williamson’s, a position he held for a decade; a decade which saw far-reaching changes in Australian theatre. Later McCallum became a pioneer of Australian television creating, amongst others, the iconic series Skippy.

McFarlane, a noted authority on early British cinema, is on safe ground when discussing their early film work but when it comes to theatre his footprint is a bit shaky. He misses entirely the ground-breaking influence McCallum had when he cast Australian leads in imported American musicals in the 60s.

As far as their private life goes we learn that McCallum liked tinkering with vintage cars and playing golf, whilst Withers’ liked decorating houses and wearing hats. “Does anyone still wear a hat?” Apparently Withers’ did. All of this inconsequential stuff is gleaned from publicity puff-pieces written for (mostly) the Australian Women’s Weekly. The editing of the manuscript also appears to have been a bit hasty with facts established in one chapter repeated in later chapters as new information.

It’s a non-critical valentine to these two enormously influential actors and their body of work. The photographic research nicely illuminates the text and whilst there’s an index, the book would have benefited by a listing of their film, TV and stage credits.

Everything's Coming Up Profits – The Golden Age of Industrial Musicals by Steve Young & Sport Murphy (Blast Books US$39.95).

Everything's Coming Up Profits – The Golden Age of Industrial Musicals by Steve Young & Sport Murphy (Blast Books US$39.95).

Industrial musicals have been around for a long time, but as this book documents, their hey-day was the 50s, 60s and 70s. From cars, fashion, bathrooms, whisky, beer, soap and shampoo to Xerox machines and everything in between it seems there has been an industrial musical written about it.

During this “golden age” a sales convention was not a sales convention unless it came with its own show, sometimes small-scale, but frequently on a canvas as large as any mainstream Broadway musical. Frequently with original music and lyrics, but not always, this fascinating book discusses the LP and EP recordings that have survived from this period and reproduces their amazing artwork. It’s a treasure trove of delights.

Who knew that Kander and Ebb wrote an industrial for General Motors in 1966 called Go Fly A Kite, or that Bock and Harnick, long before they became famous for Fiddler on the Roof, created the 1959 Ford Tractor musical Ford-i-fy Your Future. Walter Marks, whose Broadway credits include Golden Rainbow and Bajour, also shared a co-writing credit on Go Fly a Kite. Going Great was a 1964 industrial for Rambler written by Hank Beebe and Bill Heyer, who would later surface off-Broadway with the 1975 revue Tuscaloosa’s Calling Me…But I’m Not Going. It contains what the book claims is one of the best “Industrial Show Rhyme Hall of Fame” lyrics - “How could anyone pass a door, where they sell an Ambassador.”

But it wasn’t just the top-flight Broadway composers who worked these gigs; Broadway stars frequently headed the bill in between stints on the Great White Way. The songs were first class, the standards were high, and the pay more than paid the rent. Chita Rivera was the star of 1000 and One, an Oldsmobile show based on the musical Kismet, choreograped by Carol Haney. Florence Henderson also did several shows for Oldsmobile; the 1957 This Is Oldsmobility, 1958s Good News About Olds, 1959s Who Could Ask For Anything More, and later 1961s You’re the Top. Edie Adams (Li’l Abner) headed the cast of Singer Sewing Machines’ First Annual Sewing Fashion Festival in 1956, with Dorothy Loudon (Annie) headlining for the same company in 1960 with Sing a Song of Sewing. Hal Linden, Bill Hayes, Loretta Swit and Frank Fontaine are just some of the names that keep cropping up.

Australia even gets a mention with an entry for a recording from Ford’s 1959 convention, The Theme is Ford. The main text is written by Steve Young, with sidebar essays by Sport Murphy. Young’s prose captures the eras, the wackiness, and the lyrics in loving detail, while Murphy’s pun-filled observations are full of clever smart-alecky wordplay. It’s a good read. The authors also rate the scarcity of the entries, with 1 being impossible to find, 2 being rare, 3 scarce, and 4 relatively common, and have set up a website, www.industrialmusicals.com where you can hear some of the music.

Vanessa – The Life of Vanessa Redgrave by Dan Callahan (Pegasus Books U.S.$20.80).

Vanessa – The Life of Vanessa Redgrave by Dan Callahan (Pegasus Books U.S.$20.80).

Vanessa Redgrave’s acting career has frequently been hi-jacked by her political activism, but despite being ‘blacklisted’ and out of favour at times, she remains the only British actress to ever win the Oscar, Emmy, Tony, Olivier, Cannes, Golden Globe and the Screen Actors Guild awards. Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams called her “the greatest living actress of our times” and Dan Callahan’s book goes a long way to endorsing that claim.

Born in 1937, the eldest daughter of Michael Redgrave, she originally trained as a ballet dancer, but at 6 foot tall soon realised she was never going to make it in that field. She trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London, but quickly dropped out declaring it was not for her. She later did likewise with the Actors Studio in New York. Her style of performance therefore owes a little to both and a lot to her theatrical heritage. She had her first starring role in Robert Bolt’s The Tiger and The Horse (1960) in which she co-starred with her father. Her notable on stage performances in London and on Broadway have been The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1966), The Aspern Papers (1984), Long Day’s Journey Into Night (2003), Orpheus Descending (1989), Vita and Virginia (1994) and Driving Miss Daisy (2010). She has made over 80 films and has been nominated for an Oscar 6 times, winning for Julia (1977).

In the 60s Redgrave joined the Labour Party but found their ideology too “wishy-washy” for her so she quit. Later in the 1970s she and her brother Corin joined the Workers Revolutionary Party, an organisation described by one of its former members as a cult not unlike Scientology. She ran for Parliament twice as a party member but only received 700 votes the first time and 500 the second. Her support for the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) saw her fired from a Boston Symphony Orchestra performance. She promptly sued.

Redgrave has had three major lovers in her life; film and stage director Tony Richardson, who was her first husband and like her father was openly bi-sexual, Franco Nero, her Camelot co-star, who she later married in 2006 after an enduring 40-year relationship, and a 20 year on-again/off-again affair with actor Timothy Dalton.

Throughout her life Redgrave has never done things by halves, always giving her all, even if her choices were sometimes bizarre. She once picketed Actors Equity to allow porn stars to become Equity members; during the run of Orpheus Descending she decided on the whim of the moment to make her entrance fully-naked; and once whilst filming Camelot and singing “Then You May Take Me To The Fair” she began to sing it in French. Director Joshua Logan was horrified, but ultimately sanity prevailed and she did it in English.

Callahan is an obvious fan and his research is monumental, even documenting little-known cameos in obscure movies (some foreign) that had limited release and barely even made it to DVD. His prose at times is two notches above a New Idea expose, but the book does dot all the i’s and cross all the t’s in the life and career of this remarkable actress.

The Gershwins and Me – A Personal History in Twelve Songs by Michael Feinstein (Simon & Schuster U.S.$45.00).

The Gershwins and Me – A Personal History in Twelve Songs by Michael Feinstein (Simon & Schuster U.S.$45.00).

At the age of 20 in 1977 Michael Feinstein became Ira Gershwin’s archivist, a position he held until the acclaimed lyricist died 6 years later in 1983. This book is his personal tribute to Ira, George Gershwin and the Gershwin legacy. By looking at the creation and performance of 12 of their most famous songs which include “Someone To Watch Over Me”, “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” and “I Got Rhythm”, Feinstein not only fills in their career highs and lows, but also manages to give an overview of the Broadway musical of the times - the 1920s and 1930s. Funny Face, Lady, Be Good, Girl Crazy and Oh, Kay!, were just some of the hit shows they wrote, and Gertrude Lawrence, Fred Astaire and Ethel Merman were among the performers who became overnight stars in their shows. But the Gershwin legacy is overpowered by their masterpiece, Porgy and Bess, and George’s groundbreaking Rhapsody in Blue. Feinstein asserts that without Gershwin and Porgy and Bess there would have been no West Side Story or Sweeney Todd as both Leonard Bernstein and Sondheim were in awe of his achievement. Although Ira continued to write following George’s early death in 1937, and had later hits with Lady in the Dark (1941) and A Star Is Born (1954), Feinstein believes he never really got over the loss.

The book is full of anecdotes (Richard Rodgers was insanely jealous of Gershwin), but it paints astute pictures of both men, who were opposites in temperament and tastes. Along the way Feinstein also manages to throw in some of his own comments about Broadway musicals today (he likes Hairspray and Jersey Boys) and laments the loss of piano bars and clubs where patrons can hear songs from the “Great American Songbook”.

It’s a handsomely produced book with lots of photos, sheet music and program covers, and scrapbook musical sketches for possible ideas for future songs. The most unique is the two-stave sketch for “I Loves You Porgy”. There is no index but the book does come with a newly recorded CD of the 12 songs, sung by Feinstein with piano accompaniment by Cyrus Chestnut.

Loverly - The life and Times of My Fair Lady – Dominic McHugh (Oxford U.S.$28.76)

Loverly - The life and Times of My Fair Lady – Dominic McHugh (Oxford U.S.$28.76)

When I finished reading this book it made me want to get out the Original Broadway Cast Recording of the show and play it to experience the magic of Lerner and Loewe’s wonderful score all over again.

Everything you have ever wanted to know about this musical theatre classic is documented in this book with author Dominic McHugh uncovering some interesting facts for the first time. Alan Jay Lerner, the show’s book and lyric writer, Cecil Beaton, the designer, and the stars, Rex Harrison, Julie Andrews and Stanley Holloway, have all written about their experiences with the show, but in order to be complete McHugh has purposely culled his facts from other sources; the papers of composer Frederick Loewe, producer Herman Levin, publisher Warner-Chappell, and one of the original production entities, the Theatre Guild. Only when no other source was available did he resort to using information in Lerner’s two books on the subject, because, as he discovered, Lerner did not always remember things as they really were.

McHugh received his Ph D from King’s College, London, for a dissertation on the genesis and autograph sources for My Fair Lady, and Loverly is an adaptation of that thesis. But although its basis is a thesis, not for one moment is it dry and academic. It is just a well-written scholarly account of the creation and production of this hit musical. Lyrics for songs originally written for the character of Henry Higgins, “What Is a Woman”, “Please Don’t Marry Me”, “The English” and “Lady Liza”, are included along with lyrics for “Shy”, an early song for Eliza that closed the first act.

The show had its pre-Broadway opening in New Haven and it was there that the authors cut 15 minutes from it, removing the songs “Come To the Ball”, the “Dress Ballet” and “Say a Prayer”. The latter later turned up in the movie Gigi. McHugh also indulges in minutia, discovering the two bars of scene change music leading from “I Could Have Danced All Night” into the “Ascot Gavotte” were originally written by Loewe in 1941 and come from a song he authored with John W. Bratton called “The Son of the Wooden Soldier”.

McHugh claims that some people believe My Fair Lady is just George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion with music.Not true he says, there were several hundred changes to Shaw’s text in the adaptation along with the addition of completely newly invented episodes. But more importantly, Lerner and Loewe’s treatment of the Eliza-Higgins relationship is better in the musical than in the play. It is not a conventional Broadway musical happy ending but one that is much more ‘tantalizingly ambiguous’.

For anyone interested in the craft of developing a musical it is a must read. The book comes with Appendices on the cut material, notes on the sources, a Bibliography and Index.

Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art In A Time Of War (Carol J. Oja) (Oxford U.S.$24.27)

Bernstein Meets Broadway: Collaborative Art In A Time Of War (Carol J. Oja) (Oxford U.S.$24.27)

Like Loverly, this book is one in the Oxford series Broadway Legacies. Looking at the creation of Leonard Bernstein’s first Broadway productions, Fancy Free and On The Town, its publication is timely, what with Fancy Free having just recently been performed for the first time in Australia and On The Town currently back on Broadway. But it’s not only about Bernstein but also his esteemed collaborators Jerome Robbins, Betty Comden and Adolph Green, who, with Bernstein, all went on to become Broadway royalty creating West Side Story, Bells Are Ringing, Will Rogers Follies, Gypsy and Fiddler On the Roof.

In 1944 the 25-year old Bernstein had his first major success composing the score to Robbins’ 30-minute ballet Fancy Free. Robbins’ inspiration for the ballet about three sailors on shore leave in New York City was a 1934 painting by Paul Cadmus titled The Fleet’s In which was interpreted as having bisexual overtones. According to author Carol J. Oja, these were carried over to Fancy Free, which had a distinct homoerotic strain which she believed stemmed from the fact that all male creatives who worked on it had affairs with each other; Robbins, Bernstein, designer Oliver Smith, and cast members Harold Lang and John Kriza.

The ballet was so successful that later in the same year it became the fully-fledged Broadway musical On The Town, with writers (and cast members) Betty Comden and Adolph Green providing the book and lyrics. On The Town was one of the first Broadway musicals with an integrated cast; the leading lady Sono Osato was Japanese American and there were six African Americans in the cast. At the time it was groundbreaking but also ironic. While Osato was being acclaimed for her performance, her father was suffering the indignities of being interned on trumped up charges that he was a Japanese collaborator.

The book also documents Comden and Green’s beginnings in The Revuers, a group of performers who at one time included Judy Holliday and Bernstein and who specialised in skits that were satirical and mostly played left-wing venues. Oja, who is a Professor of Music at Harvard University, writes with authority, especially on Bernstein’s music which she believes in the beginning was greatly influenced by the work of Aaron Copeland who was a mentor and lover. She also writes at length about the black performers and where their careers went following the success of On The Town. It’s not only a succinct summation of the initial work of Bernstein, Robbins and Comden and Green, but a fascinating appraisal of attitudes, the period, and wartime on Broadway. The book comes with several pages of music (it helps, but is not essential, if the reader is musically savvy), plus some black and white photographs, source notes, discography and index.

Theatre World – Volume 68/2011-2012 by Ben Hodges & Scott Denny (Applause US$36)

Theatre World – Volume 68/2011-2012 by Ben Hodges & Scott Denny (Applause US$36)

This new volume of Theatre World takes in the 2011-2012 Broadway, Off-Broadway, Off-Off-Broadway, and regional theatre companies seasons. It was a bumper year for musicals; Newsies, Nice Work If You Can Get It, Once, the ill-fated Spiderman, and revivals of Follies, Porgy and Bess, and Evita, and a not too shabby one for plays; Other Desert Cities, Venus in Fur, The Road to Mecca, and One Man, Two Guvnors.

Off-Broadway entries include; Cock, SILENCE the musical, and revivals of Rent and The Man Who Came To Dinner. The book details over 1000 shows and lists cast, replacements, producers, directors, authors, composers, opening and closing dates, song titles, plot synopses, and production photographs for every one.

Now in its sixty-eight year of publication, it’s a book that excites with its visual documentation and an essential read for theatre aficionados.

Not My Father's Son – A Family Memoir by Alan Cumming (Cannongate US$15.99).

Not My Father's Son – A Family Memoir by Alan Cumming (Cannongate US$15.99).

The only way to describe Alan Cumming’s autobiographical book Not My Father’s Son is that it’s compulsively readable. A page-turner if ever there was one and something you will want to read in one sitting. Cumming uses his appearance on the BBC TV series Who Do You Think You Are? to tell the story of his childhood experiences growing up in Scotland with a violent father and his search to find out the true story of his maternal grandfather who disappeared to the Far East after the Second World War. The book is divided into chapters of “then” and “now”, with the “then” sequences of the brutality of his childhood being particularly harrowing, and the “now” sequences moving from Scotland to Malaysia to solve the mystery of his ancestors. It’s an honest and open well-written account of his family that evokes passion, rage and respect. Highly recommended!

Diary of a Mad Playwright by James Kirkwood (Applause US$16.95)

Diary of a Mad Playwright by James Kirkwood (Applause US$16.95)

With Hayley and Juliet Mills touring the country in James Kirkwood’s Legends it’s time to revisit Kirkwood’s account of what happened on the road with the first production of the play, which starred Carol Channing and Mary Martin.

Written in 1989, Diary of a Mad Playwright is as pertinent today as it was back then. Theatrical bad-behaviour doesn’t date, it only gets more salacious, and there’s no shortage of it in this book. Anyone who has ever written a play, produced a play, or had anything to do with actors will associate like crazy with every page of this bitchy, gossipy and acutely funny book.

Mary Martin, star of South Pacific, Peter Pan and The Sound of Music, and Carol Channing who indelibly put her stamp on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and Hello Dolly, would appear to be a match made in heaven but it ended up a match made in hell. Martin at 73, making her first appearance on stage for 15 years, was insecure and couldn’t remember her lines. Channing was frustrated, and with a director who was absent a lot, and an inexperienced producer who constantly interfered, the production was fraught from the beginning.

Kirkwood’s account from when the play opened in Dallas until it closed one-year later in Palm Beach after playing 300 performances is theatrical gold.