Designing KING KONG: The Creature, The Sets and the Costumes

Spectacular musical KING KONG has its premiere at Melbourne's Regent Theatre in June 2013. We go behind the scenes to earn about the creation and operation of the creature, and the costume and scenic designs for the show.

The Beast / God Kong: Creating a Creature

Five years in development, four years in the animatronics workshop, numerous design ideas – creating Kong has, in the understated words of Creature Designer Sonny Tilders “been a serious challenge”. In a way, similar to the challenge Wallis O’Brien faced in 1932 when he worked out how to make an 18-inch steel-framed puppet covered in rabbit fur appear ‘live’ on film interacting with Fay Wray. Just like now, it had never been done before.

With Global Creatures’ world-renowned expertise in animatronics proven with T-Rex and co. in Walking With Dinosaurs, then upped in complexity with flying dragons in How To Train Your Dragon, the obvious first thought was to have a super-realistic, high-level, high-tech animatronic creature that could do things in a theatre that had never been done before. “It was going to be the most complex creature we ever made,” recalls Tilders.

Over the ensuing years the complexity remained (if not increased), but the wholly animatronic, multi-axis, hyperreal vision gave way to what Kong is today: a stripped back, sculptural creature, part marionette part animatronic, operated by a combination of hydraulics, preset automation and manual manipulation.

One of the earliest decisions was to not go down a hyper-real path realising it was a hiding to nothing. What can be achieved on film with CGI – and Peter Jackson’s version did Kong beautifully – was simply not possible on stage. This led directly or indirectly to another key decision: to have direct manipulation by performers on stage. Not blacked out, but visible and a dynamic part of Kong. These 11 aerialist/puppeteers have been named “The King’s Men”.

One of the earliest decisions was to not go down a hyper-real path realising it was a hiding to nothing. What can be achieved on film with CGI – and Peter Jackson’s version did Kong beautifully – was simply not possible on stage. This led directly or indirectly to another key decision: to have direct manipulation by performers on stage. Not blacked out, but visible and a dynamic part of Kong. These 11 aerialist/puppeteers have been named “The King’s Men”.

The success of The Lion King, and more recently War Horse, has been an inspiration during the development of KING KONG. Says Daniel Kramer: “They are wonderful reminders that much of the magic of puppetry is in seeing the puppeteer(s) – the double vision of both the creature’s life and the human beings creating that illusion; the audience’s imagination participates in this process, thereby projecting their own emotions onto the creature. So when a creature is injured or wronged, a part of the audience, our psyche, is wronged.”

The core chassis of Kong is one of the company’s ‘simpler’ understructures, however mixing the anomalies of a gorilla’s anatomy with the principles of engineering, which loves straight lines and good planes, represents the core challenge of animatronics. Says Tilders, “It’s the difference between what we do and what robot makers do. We’re trying to get the robot out of it.”

On top of the chassis is a layer of inflatables - air powered muscles - which give Kong a lightweight body form. Over the top of that are a series of highly sculptured muscle bags that stretch and contract to make it seem like there is a whole anatomy that lies underneath. For the first time these bags will be exposed rather than hiding them, a deliberate move to emphasise Kong’s muscularity and power. “I see him as a giant sculpture,” says Tilders, “Like your classic Greek form. His proportions are absolutely pushed.”

… And Making Him Breath

… And Making Him Breath

As Puppetry Director, Peter Wilson’s job – as it has been over a 37-year career that started at Melbourne’s Handspan Theatre – is to “animate the inanimate”. But even he concedes operating Kong is probably the most complex puppet he has ever worked with, simply because it involves three layers of animation and 14 people to operate. Although Kong can be described as a hybrid animatronic/marionette, by its use of visible, fully engaged puppeteers it is also akin to the 300-year-old Japanese technique of Bunraku.

“It’s my job,” says Wilson, “to give Kong a complete liveability, a spirit and a soul. There needs to be a reason and a purpose to every move.” Every action of Kong involves these three departments working together finding the elements that will make the audience believe Kong is, for one, a quadruped. “I need to impart the idea that the full weight of Kong has integrity as he moves across the stage,” says Wilson, who will need to plot out every single position that Kong takes.

At a higher level Wilson, as all good puppeteers do, aims to understand the “breath” of Kong. “It’s most important that our audience sees that he is breathing: that he’s got a brain or an intelligence and that he is capable of making decisions.” The challenge for Wilson, and the performers and technicians who will manipulate Kong, is to maintain that emotional engagement for every second he is on stage so that the audience will suspend their disbelief throughout his entire journey.

The 11 puppeteers who will operate Kong on stage will be an all-male team drawn principally from the ranks of circus artists. Off stage, two puppeteers will operate the animatronics via “voodoo” controls and one crew member will operate the automation. Wilson will be providing the puppeteers with intensive training in the art of puppeteering, which will include the mental orientation of thinking through the puppet. “A puppeteer has this absolute awareness of everything on stage but it is all seen, observed and felt though the character,” says Wilson. Not that he foresees any problems with the training: “Circus boys are fantastic because they understand the physical and are incredibly disciplined.”

With puppetry enjoying resurgence on the mainstage in recent years, Wilson believes what is being attempted in KING KONG is without precedent. “I’m amazed at the technology and what Sonny’s created – he’s just a genius,” he says.

… With The King’s Men

Working hand-in-hand with Tilders and Wilson is Aerial/Circus Director Gavin Robins, a former member of the aerialist group Legs On The Wall and now a worldwide specialist in circus and physical theatre. Most recently, a Churchill

Fellowship has taken him through the US investigating the latest technologies in animating the body for stage and screen. Says Robins, “When I heard about KONG I thought this is exactly how I would love to be working - with new technologies and physicality.”

He will be working across the production, however with Kong his brief is focussed on The King’s Men - 11 highly skilled, extremely strong, physically virtuosic young men who are versatile enough to embrace puppetry skills as well. Says Robins, “We are championing this notion of a brute strength emanating from Kong. The King’s Men are representing the persona, the aura and the real male energy of Kong.”

During the long development process, Global Creatures used its connections with Melbourne’s National Institute of Circus Arts to test out some of their ideas. “We’ve called on their graduates or third year’s and said ‘come along’.

They’ve been a really great resource and it’s a brilliant facility in Australia.” For Robins, circus performers have been a perfect match for the production: “There’s a real sense of ensemble. You’re bringing this beast alive on stage and I think just to be a part of that image and that energy has been a thrill for them, because they’re into the idea of mastering a skill and finding the ability to do something extraordinary with their bodies.”

Images above: Kong Development Face; Kong Development - 3D Computer Model of Kong &Kong Development - Schematic Drawing of Kong NYC Rampage. Credit: Global Creatutres.

A Tale of Two Islands: Creating the World of King Kong

A Tale of Two Islands: Creating the World of King Kong

Peter England is perhaps unusually qualified for a production designer to talk on the ‘whole show’level. He is one of the trio –the others being Carmen Pavlovic and Sonny Tilders –to have been involved in KING KONG from the very beginning,

not only working on preliminary spatial and feasibility designs with Tilders but also doing a large amount of research on the story and background: from histories and biographies through to contemporary theory and academic treatise.

This foundation level of interest in the story goes directly to England’s philosophy and approach to the stage design.

“In many ways KING KONG is a monumentally simple story –at its heart a ‘Beauty and the Beast’myth,”he says.

As a great believer in ‘less is more’, England has strived to create “a world that meets this simple iconic boldness.”

The overall stylistic conceit for the show is similarly aimed at an aesthetic simplicity. “We’re capturing the spirit of

New York 1933, but we’re not doing a historical museum piece; we’re injecting the production with a healthy dose of modern theatricality.”

On a conceptual level England and director Daniel Kramer talked at length about the story in terms of it being a timeless, cyclical ritual: the rise and fall of a species in evolution, the rise and fall of empires in civilisation. Says England, “On a more detailed level we uncovered similar cycles within the story structure and arrived at one very simple visual expression of this –the Moon. At times it is just the Full Moon that sets the stage. There is something gloriously powerful and potent about this simplicity.”(It is from this image that the production’s logo was born.)

One of the great architectural challenges of the production design was how to represent New York City. For this England took inspiration from the iconic 1930s photographs of construction workers up on I-beams when the city’s most famous and tallest buildings went up (the Chrysler Building, the Rockefeller Centre and, of course, the Empire State Building). “Those photos are rich with the spirit of industry that was so particular to NYC during the Great Depression,”says England. “They also conjure up fearlessness and danger. Whilst the rest of America struggled, somehow a towering Empire was built on Manhattan Island. This is the inspiration behind our stage aesthetic for NYC; an Empire of I-beams … way up in the clouds.”

Achieving a perception of great height has been a standout goal in the production’s design. Kong famously climbs to the highest point on two separate islands, both times carrying Ann. First to his mountain summit lair overlooking his kingdom of Skull Island and then at the end of the story he climbs to the highest point in NYC - the top of the Empire State Building. Says England, “It has been essential we create for the audience a sense of great verticality to achieve this. There is a consistent suggestion in the staging that we are climbing higher and higher scene by scene.” To achieve this England has incorporated into the design the very highest and very lowest spatial opportunities the theatre can offer. “We’re building this set from the theatre’s basement to its very highest point – there’s hardly an inch we’re not using. By doing this we are then allowing much of our scenery, and indeed our cast, to enter and exit from above or below, not just from the sides. This creates a sense we are moving from scene to scene vertically rather than via the more traditional horizontal entrances and exits.”

Achieving a perception of great height has been a standout goal in the production’s design. Kong famously climbs to the highest point on two separate islands, both times carrying Ann. First to his mountain summit lair overlooking his kingdom of Skull Island and then at the end of the story he climbs to the highest point in NYC - the top of the Empire State Building. Says England, “It has been essential we create for the audience a sense of great verticality to achieve this. There is a consistent suggestion in the staging that we are climbing higher and higher scene by scene.” To achieve this England has incorporated into the design the very highest and very lowest spatial opportunities the theatre can offer. “We’re building this set from the theatre’s basement to its very highest point – there’s hardly an inch we’re not using. By doing this we are then allowing much of our scenery, and indeed our cast, to enter and exit from above or below, not just from the sides. This creates a sense we are moving from scene to scene vertically rather than via the more traditional horizontal entrances and exits.”

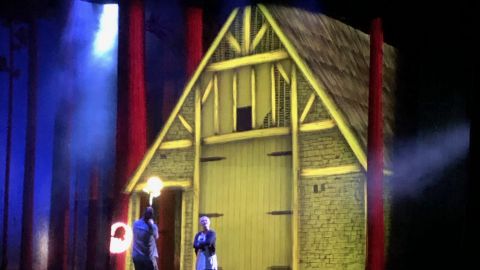

With locations ranging from a theatre, to the loading docks of NYC, to a boat on an ocean, to a jungle, to the top of a mountain, to a Broadway theatre, to the streets of NYC and then, of course, to the top of the Empire State Building, a production of KING KONG is always going to come with enormous challenges. For England this is where he finds the greatest joy in his work: “To create for an audience some simple, bold gestures that clearly tell them where they are, that thrill them as to how they spectacularly got there and at the same time have the power and epic proportions worthy of such a gigantic legend – this is what I love so much about stage design. Creating a spectacular visual journey of imagination that allows a story to be told clearly and freely, with power, emotion and focus.”

Director Daniel Kramer, says England, “Has pushed this production to greater heights as far as its theatrical artistry goes.” Both men share a connection to opera and England believes the aspects of that art form that Kramer has brought to KING KONG have been “absolutely right.” For England, there is one opera production he has done that has emotional parallels to KONG – his (much admired) production design for Opera Australia’s Madama Butterfly and not just for the pared down beauty of its physical set. Says England: “There’s something about the simple poetry of the love story between two people from radically different worlds, whose fate leads to separation and finally some very painful choices – and sacrifice – that somehow resonates with KONG.”

England has found the four years working with Kramer, often remotely, enormously enjoyable. “The way he works with everyone is inspirational and generous. He has a clear vision and an exceptionally imaginative take on theatre, but simultaneously he has a most wonderful hunger for more and different ideas and a beguiling gift of collaboration.”

Set images: Concept Drawing of NYC I-Beam Motif & Set Model of Kong Breaking Out Of Time Square Theatre. Credit: Peter England.

Thirties Meet Now: The Costumes

Thirties Meet Now: The Costumes

The Tony® Award-winning Autralian costume desiger Roger Kirk has specialised in the stage, and in particular music theatre, designing costumes that not only look spectacular, but are engineered for dancing and very quick changes.

Over the three years he has been on KONG, he has produced many beautiful drawings, which have necessarily had to evolve as the script has evolved, but “that’s what’s made it interesting really.”

With the knowledge that Daniel Kramer was not interested in a purely period piece, Kirk has arrived at a position on the look of the costumes: “1930s meets fashion meets music video clips.”

Kirk has a particular reputation for designing to flatter the female form and audiences can look forward to seeing some very sexy outfits in the chorus line of KONG: “Dancers are usually gorgeous girls so you want to make them look fabulous. If you can’t make a girl look gorgeous, what’s the point?” he states. Kirk is planning to assemble a workshop in Sydney around Christmas time to begin making the costumes, running in tandem to the rehearsal period. He is also eagerly anticipating the day when he can hear the orchestra and cast sing together for the first time: “I’ve been doing this for a thousand years and I always think it’s the most exciting time. It’s something to do with musicals – as soon as that music starts, ‘bang’, you’re gone.”

Costume Sketches: Roger Kirk.