The Histrionic

Though it may all be relative, it’s a truism to say there is good theatre and bad theatre; and most theatre falls somewhere in between. Then there are the nights of magic; theatre which is so special and exhilarating that you scarcely dare talk about them for fear of discovering how the magic was done, and destroying the illusion. These nights are few and far between and, like a child allowed to stay up late, you don’t want the night to end.

Opening night of Bernhard’s play The Histrionic falls into that last category. The play itself, seldom performed, owes as much to Kafka, and even Gogol, as it does to Beckett and Ionesco. It’s a dark and empty place within that the main character comes from, even though the play is achingly and hilariously funny throughout. Slapstick plays with a sub-text of tragedy, and they’re a comfortable fit. And, whilst Bernhard’s biting yet absurd quasi soliloquy rails against the subjugated fascism and banal mediocrity of his homeland, (Austria) Tom Wright’s brilliant new translation dazzles us with shards of absolute clarity throwing light on the twisted soul of Bruscon, an actor reduced to playing in pubs in little more than villages, whose giant ego is largely a prop to shield from his withering soul the fact that his play may be rubbish, and he is a mediocre actor after all. He’s a “National Treasure” at the mercy of “projectile provincialism.”

We may not all be actors, but we’ve all spat the dummy, thrown tantrums, and gone on the attack when we are most defensive. We have all indulged in grandiose grand-standing when we know we are inadequate. We are most lethal when we are most vulnerable, and most blind when we are afraid to see the truth. Bruscon tells us we are monsters in order to be human. It’s a mirror for us all. I come from a long line of Histrionics – and so I related entirely to Bruscon. My heart broke for him even as he monstered his children, raged tyrannically, and obsessed on whether the fire exit light would go out to give him a total blackout at the end of his play – a “comedy” (complete with Greek masks) entitled “The Wheel of History”.

We may not all be actors, but we’ve all spat the dummy, thrown tantrums, and gone on the attack when we are most defensive. We have all indulged in grandiose grand-standing when we know we are inadequate. We are most lethal when we are most vulnerable, and most blind when we are afraid to see the truth. Bruscon tells us we are monsters in order to be human. It’s a mirror for us all. I come from a long line of Histrionics – and so I related entirely to Bruscon. My heart broke for him even as he monstered his children, raged tyrannically, and obsessed on whether the fire exit light would go out to give him a total blackout at the end of his play – a “comedy” (complete with Greek masks) entitled “The Wheel of History”.

Apart from the text, this production gives us three stars symbiotically entwined in the theatrical firmament. Their combined light brings brilliance back to the theatre, which seems to have been languishing in the shadow of an eclipse for several years.

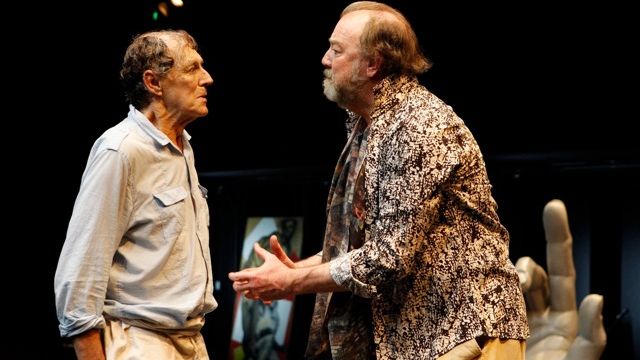

Bille Brown gives the performance of his illustrious career in the part of a lifetime. The sheer marathon proportions of what are largely monologues for one hour and forty minutes are staggering. He postures, he pouts, he rails, he rants. He terrorises and obsesses and can cut his own children to shreds with a look, a gesture. He is both effete and overpoweringly masculine; flamboyant and fragile; a Drama Queen and King Lear. He walks the tightrope of over-the-top hysteria and only rarely crosses the line to dip his big toe into the waters of burlesque. But even that seems intentional and part of Bruscon’s “how much will people put up with?” mentality. My grandmother used to say of such an actor, in her smoke-laden voice “He’s just TheatAH, Daahling.” We may not recognise the type now, but his kind trod the boards, just as surely as dinosaurs walked the earth. In Melodrama, the leading man never turned his back to the audience and asides were made after a move requiring three steps downstage. That’s the world of Bruscon. Tragic and tyrannical, he is hateful and pitiful in equal measure. It’s a performance to be treasured and acclaimed, and though Brown has given us masterful performances in the past, it seems that all of them were preparation for this visceral yet totally artificial Bruscon. He is not to be missed.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Barry Otto is one of our finest actors in any medium. He has no more than a handful of lines in the entire play, and yet he is omnipresent. His face is elastic, his jerky movements and the “pecking” mechanism of his neck reminded me (in the nicest possible way) of an animated chicken. Otto is that rarest of creatures, a RE-actor. No standing quietly waiting until it’s his turn to speak, (why do so many actors do that?), he is internally busy throughout, knowingly out of his depth with Bruscon, yet trying valiantly to understand the torrent of verbiage he is subjected to, to process and absorb it, and reply in a manner which makes him seem more intelligent that he actually is. It’s a performance that’s as energising in its own way as Brown’s. You can virtually climb into Otto’s skin and see the wheels turning, the thought processes at work. Simply stunning!

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Barry Otto is one of our finest actors in any medium. He has no more than a handful of lines in the entire play, and yet he is omnipresent. His face is elastic, his jerky movements and the “pecking” mechanism of his neck reminded me (in the nicest possible way) of an animated chicken. Otto is that rarest of creatures, a RE-actor. No standing quietly waiting until it’s his turn to speak, (why do so many actors do that?), he is internally busy throughout, knowingly out of his depth with Bruscon, yet trying valiantly to understand the torrent of verbiage he is subjected to, to process and absorb it, and reply in a manner which makes him seem more intelligent that he actually is. It’s a performance that’s as energising in its own way as Brown’s. You can virtually climb into Otto’s skin and see the wheels turning, the thought processes at work. Simply stunning!

And then there’s Daniel Schlusser, who surely now has cemented his position as our most visionary and bold director. His blocking is near perfect on a thrust stage that could prove problematical with an audience at right angles. The scene with the curtain is perfection and his skilful use of the rest of the space to create a larger world is breathtaking. His understanding of the text and of his actors is illuminating and brave. Though this play may be crueller than any of Beckett’s offerings (and funnier) Schlusser finds the humanity in the sub text of his characters. He uses the audience. He confronts us, alarms us, and then retreats, drawing us into a theatrical world that repels and moves us simultaneously. He is an artful master of his craft.

The ensemble cast are well balanced, and lend great support, but ultimately they are fodder for Bruscon’s verbose appetite.

Bruscon says at one point “Critics! Empty skulls staring at empty images - No-one listens to the words any more.” We do when the words are worth listening to, and when theatre reminds us of why we loved it in the first place.

Coral Drouyn

And a review by Martin Portus from the Sydney season.

Austrian playwright Thomas Bernhard so hated his homeland he decreed that after his death his work never be performed there. Now it is – and he’s a national hero.

This loathing of all things Austrian drives the histrionics of Bernhard’s Bruscon, a celebrated actor arriving at a dishevelled country pub to set up for his show, The Wheel of History, surrounded by wide-eyed locals and his own victimised family.

In what is essentially a monologue, Bruscon rants against the tyrannies and mediocrities of his society (and the theatre), while embodying most of these sins himself. He is actorly self-obsessed, dictatorial, cruel, bullying, needy and mawkish, and in place of any sincerity devoted to the grandiloquent gesture.

Bille Brown delivers this demonic showman with full power and mercurial diversity. What’s missing are any readable cracks in the tyrant’s façade, his vulnerabilities, to help illuminate the source and real targets of all this polemical loathing.

Like Hitler, whose tattered image still hangs in this Austrian backwater, Brown’s demagogue begins as riveting but ends as inscrutable. Daniel Schlusser’s production adds great entertainment with a fine cast of other oddball characters revolving around Bruscon, especially Barry Otto’s obsequious, bumpkin landlord.

And there’s vivid sculptural relief in Marg Horwell’s farmyard theatre set, cluttered with dust and Expressionist oddities. By the end these are all assembled for the (disastrous) opening performance of Bruscon’s impossible opus. The Histrionic is a cruel comedy more interesting to read about than experience.

Martin Portus

Images (from Top): Barry Otto and Bille Brown; Bille Brown, Edwina Wren and Josh Price; Bille Brown, Barry Otto and Josh Price (back) & Bille Brown (front); Edwina Wren and Josh Price (back l-r). Photographer: Jeff Busby.

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.