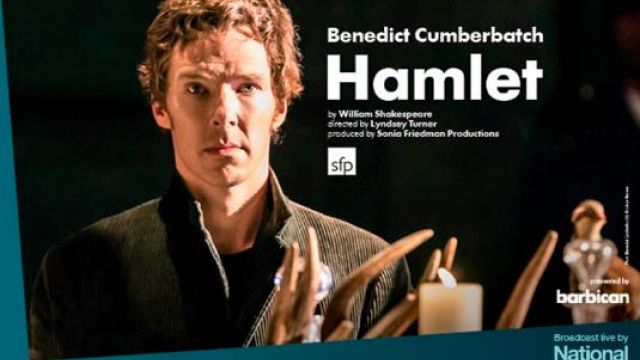

Hamlet

Benedict Cumberbatch is Hamlet – which is undoubtedly the reason the live show in London is the hottest ticket in London this year or possibly ever. (100,000 tickets sold in minutes, months before the show opened). The play Hamlet is over 400 years old and arguably the most performed of all Shakespeare’s plays, but cast ‘Sherlock’ and it becomes the hottest ticket in town.

But indeed Mr Cumberbatch is riveting to watch, displaying a number of sharply contrasting personas within the one role: heartbroken at the death of his father, angry and acidic at his mother’s blandishments, adolescent in his defiance of Claudius, hateful in his rejection of Ophelia, self-loathing for his indecision and cowardice, disturbing in his ‘antic disposition’ (although never ‘mad’), playful, witty, intellectual in his speculations, scathing in his dismissal of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, chilling about their death, a bullying prig to his mother and a fatalistic prince in his dying. While Mr Cumberbatch may seem ‘cold’ on screen (as Sherlock, say), here he is very open – warm, vulnerable, sincere. Each of his manifestations of the man Hamlet is clear and committed, solid and plausible.

But unfortunately these and other fine performances by other cast are overlaid or obscured by director Lyndsey Turner’s ‘concept’ - or is it ‘concepts’? An interpretation is one thing and Shakespeare is robust enough to survive many, but a ‘concept’ imposed on the text is something else and it can be a trap in which various unwieldy bits bulge through the bars or escape. That appears to be the case here – and the concept is Hamlet as a ‘political’ statement .

While it is an enormous and stimulating pleasure to listen to a cast that understands every word they’re saying – so that we marvel at text we thought we knew and find new things in it – we are also distracted by such things as the restructured beginning of the play. No Ghost on the battlements up first. Instead Hamlet listens to Nat King Cole on vinyl singing ‘Nature Boy’. (Apparently, worse, in previews the play began with ‘To be, or not to be…’) Then Horatio enters, just arrived; he hasn’t seen the Ghost yet… And, by the way, why does pointedly working class Horatio (Leo Brill) wear his ex-army rucksack in every scene until Act V? Why is Polonius not just sententious and long-winded but so stupid that he would have been relieved of his duties long since? Why does Hamlet, feigning madness, play inside a toy fort, dressed in a 19th century infantryman uniform? Is that a jejune comment on Denmark at war? (And is there a war? Didn’t Claudius diplomatically avoid it?)

After the intermission (the text is restructured in part but scarcely cut), we find Elsinore – previously a somewhat mouldy ‘stately home’ – piled with debris, upturned furniture and rubble. The design, by Es Devlin, complemented by Jane Cox’s dramatic lighting, is cinematic and magnificent, but it can overwhelm rather than illuminate the text. The metaphor of ruin, exacerbated by war and moral decay, is more or less clear, but it distracts by being so excessive and all enveloping. The black rubble works brilliantly for Ophelia’s exit to suicide and the Gravedigger scene, but for little else and the climactic duel takes place in near darkness. Or it seems so to the cinema audience.

Lest these ‘elements’ be a deterrent, there are sequences of great theatre just as there are some wonderful performances. Ciarán Hinds is a masterful Claudius who acts like a king even if he stole the throne. His contempt for Hamlet is only just in check but unleashed into sheer malice when Hamlet returns from England. It is as if his guilt has driven him mad. On the other hand, Anastasia Hill is a puzzling choice as Gertrude. Yes, they kiss in front of the courtiers, but where’s the sensuality, the lust that threw them together perhaps even before Hamlet Senior’s murder?

Siân Brooke as Ophelia sets up beautifully an uncertainty, a fragility that will tip into madness – and the production does not soften or poeticise that madness. It is as awful and degrading as Jacqueline McKenzie’s or Cate Blanchett’s Ophelia in Neil Armfield’s Belvoir version with Richard Roxburgh in 1995.

Karl Johnson doubles as the Ghost of Hamlet Senior and as the Gravedigger. If he lacks majesty in the former, he is brilliant as the latter – dry as skeletal bone, a cheerful cynic making no attempt to please his betters. (But why, as he digs, does he listen on his portable radio to Sinatra singing ‘All of Me’? The joke is pretty thin.) Kobna Holdbrook-Smith is Laertes; he has presence and glamour, but he comes in so full-on he leaves himself nowhere to go. Matthew Steer and Rudi Dharmalingam are an amusing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern – except that it is hard to believe that the brilliant Hamlet was ever mates with this pair – or that Claudius would set these inadequates to spy on his dangerous stepson. Here ‘wouldn’t it be funny if…’ wins out over credible.

As usual with a National Theatre Live showing, we’d rather be in the theatre to see all this than to see it filmed – ‘live’ or not. As usual, the actors on stage are projecting to a live audience - in this case in the pretty vast Barbican - but when the cameras are giving us, in the cinema, a medium close-up of a rant or some exposition it naturally feels over-cooked and over-done. But that’s an inherent problem of National Theatre Live. For, say, Skylight it works. Shakespeare? Not so much.

Lyndsey Hunter is an award-winning director. Her shows are critical and commercial hits. Perhaps it is the challenge of making fresh and ‘different’ this old ‘classic’ that has resulted in this glittering but patchy spectacle. Nevertheless, Shakespeare the playwright is undefeated. Mr Cumberbatch, chameleon though his Hamlet may be, could not be clearer – a philosopher rather than a poet, and unafraid, in this manifestation, to demonstrate that Hamlet is not a hero but his own worst enemy.

Michael Brindley

Subscribe to our E-Newsletter, buy our latest print edition or find a Performing Arts book at Book Nook.