Stephen Sewell’s Furies

Australia’s celebrated, most political, surely most impassioned playwright Stephen Sewell shares his life’s anger and achievements with Martin Portus. He decries our mainstage theatres as dominated by “exclusive gangs” bereft of artistic directors able to develop new work.

Stephen Sewell returned six years ago to live in the gritty western Sydney suburb of his childhood. With his young family, he’s back to the same Granville house, even sleeping in his old bedroom.

“Back to the roots,” he says. “When I was a boy Granville was full of Italians and Maltese; they’ve made their money and moved on, and now it’s Arabs, Asians and Africans – all incredibly nice, hard-working people – but I joke that whenever there’s a shooting in Sydney, it’s one of my neighbours. So, a good place for a dramatist.”

Here lived the former Catholic altar boy whose teenage conversion to communism still inflames his belief in individual moral responsibility and a theatre of shared confrontation and catharsis. In that bedroom he read his first book – Orwell’s 1984 – which at 13 inspired him to write.

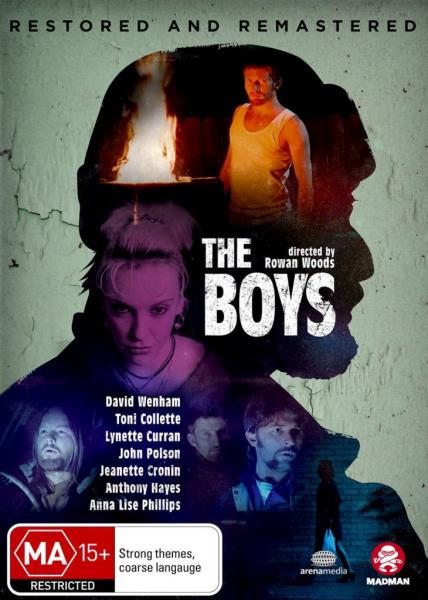

From this local hood and his older relatives – “ignorant, wild and larrikin Australians” – Sewell saw early the disappointment and suspicions, the oppression and violence that he says permeates Australia’s working class. He drew on this world for his plays, so applauded in the 1980’s, and notably to unravel the evil forces which drove those who raped and murdered the western Sydney beauty queen Anita Cobby. His screenplay for The Boys in 1998 was much celebrated.

To really penetrate this explosive masculine violence, Sewell actually ignored the Cobby case. Instead he “looked inwards to myself as a man, finding this violence and hatred of women within myself, to try to understand it and replicate it into film.” It’s a remarkable insight from a writer long distinguished by his great roles for women. And his increasing exploration of female concerns, as in his MTC premiere last year of Arbus & West, about how the famed feminist photographer met the indefinable icon Mae West.

Now from Granville, Sewell, aged 65, travels to NIDA at the University of NSW where he’s been Head of Writing for Performance since 2013. He’s also working through a kaleidoscope of different projects across his desk – multiple play scripts, films, physical theatre shows, multi-media performances, even a musical based on Patrick White’s A Cheery Soul. And he’s just completed The Lives of Eve, a play inspired by Jacques Lacan, about a female psychotherapist treating a female client unable to orgasm (he wants to direct it himself; but he’s told it will only get up if he gives it to a female director).

This irrepressible storytelling channelled into such a diversity of outlets models what is Sewell’s first lesson to his eight students every year.

“It is to go through a story, how do you tell it and how can you do so in different forms,” he says.

And, importantly, give up all hope your work will be developed or staged in Australia’s major theatres.

“The things these writers talk about are the catastrophe of global climate change, the environmental collapse; they are very political – issues of gender, women’s liberation, social justice issues. And they write very well about these concerns of people in their 20s and 30s, from direct personal experience and in a contemporary vernacular. But they leave NIDA and find their plays are rejected by the mainstage theatres, by people for whom none of these things matter.”

Instead, Sewell bitterly argues, these companies claim the occasional cutting-edge credit by restaging contemporary but well-tested plays from foreign writers. Few artistic directors here have the interest or ability to create programs to develop new work. Every year he takes his writers to the Edinburgh Festival and to London, where theatre directors, in contrast, welcome them profusely and show them extensive writing programs.

And don’t get Sewell going on the Sydney Theatre Company! Across his 40 year career, it’s staged just one of his plays, a two hander.

Not that there was much support anywhere when he started. Once young Sewell had rejected the fate of being a science teacher – and “went to Plan B which was to become a famous writer” – he remembers the horror of facing his ignorance of how to write plays.

“For the first ten years I felt suicidal every day. At NIDA I try to save my writers from that experience. Being in that state of utter despair didn’t teach me anything.”

But Sewell did thrive under the generosity of key directors and theatres, as everyone then, equally ignorant, muddled along finding ways to stage what in the 1980’s was an astonishing range of Australian plays – many of them ambitious, philosophical big cast epics. Sewell’s certainly were.

His first, The Father we loved on a Beach by the Sea, at Brisbane’s La Boite, borrowed from Orwell and projected a future military dictatorship in Australia. Next, Traitors was about the intense battle in 1920s Leninist Russia for the direction of communism; while his thriller Welcome The Bright World, set in West Germany, was crammed with political and scientific debate.

Dreams in an Empty City, about nothing less than the collapse of capitalism, with a crucifixion to end it all, premiered at the 1986 Adelaide Festival. Sewell wanted machines set up in the foyer for audiences rushing to withdraw their money. The State Bank of SA, a sponsor, complained about the play. Soon after the bank collapsed in ruins, its CEO was imprisoned, and the world faced the 1987 financial crash. Maybe Sewell was right.

“No one took their money out in time,” Sewell says with his hearty laugh. “The idea that you can seriously engage with the issues of a play, and that that can have some impact on your behaviour, is not part of our culture.”

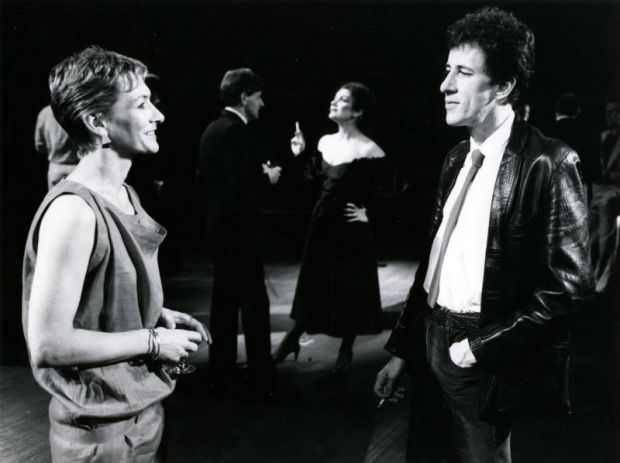

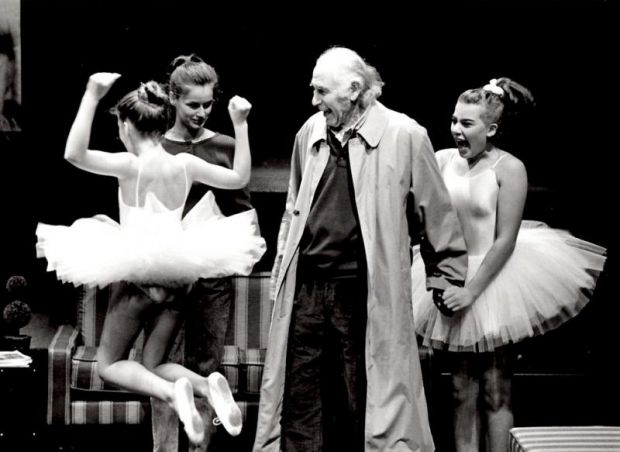

Adelaide’s State Theatre also premiered Sewell’s most celebrated play, The Blind Giant is Dancing, in 1983. It was directed by Neil Armfield, who restaged it at Belvoir the next decade, where it was restaged yet again in 2016 by director Eamon Flack.

Mirroring his own family, not for the first time, Blind Giant centres on three sons, one a party apparatchik, and their conservative working-class father – a cloth cap Tory – against the moral and political compromises of the Labor Party.

With its crackling political dialogue and rich Australian characters, this was a landmark for Sewell. He and friend, fellow writer Louis Nowra, both set early plays in foreign settings. They were dubbed the Internationalists, but the young writers were also postponing how to express ideas and passion in their own country, in the understated Australia vernacular. Somehow the lingo seemed inadequate…

“I’m still involved in trying to get under the skin, to understand the truth of this place. How can I do it when Sandy Stone (Barry Humphries’ suburban pensioner) is one of the paradigms of who we are?

“Unlike Louis, I don’t believe a play is ever really finished; it’s not a time capsule. As an artist you are always biting off more than you can chew so there are always going to be faults in any play. And decades on, I now feel I’m capable of getting these things right, so I did another draft of Welcome Bright World. And I rewrote Blind Giant for all three productions … but Eamon stayed with the original for that last one; he liked the rawness.”

Despite the success of Blind Giant, Sewell collapsed months later, depressed by what he saw as the futility of being a political writer. Like his central character, he was now without faith in communism, politics and human beings. He decided to kill himself.

But soon he took a different path, abandoning this “rational conclusion” of suicide and instead opening himself to the unconscious, and a new fascination in psychoanalysis, in fantasy and a theatre of the poetic.

This has taken him to some very dark places when career opportunities shrunk in the 1990’s and his plays explored extremes of sexual and violent behaviour. One good thing, following the end of his second marriage, and during Anger’s Love, premiered by a performing arts school in Adelaide in 1996, was meeting his current partner, designer Karla Urizer.

“The pits around this time was when I was yelling down the phone to the poor receptionist at Belvoir Street, and saying, don’t you know who I am?”

“And she didn’t!” (huge laugh)

He was increasingly writing for film. Theatre though was still delivering him moderate hits like The Sickroom (Playbox, 1999) about a corrupt stockbroker and his dying daughter, and earlier The Garden of Granddaughters, about a dying Jewish conductor returning to his three warring daughters. Death was around every corner.

Miranda, about two strangers, one a war journalist, in a one-night stand of sex and drugs, Sewell describes as “a roller coaster ride on razor-blades”. He later reworked the play into the first film he directed himself, Embedded, in 2016.

Sewell’s push to the poetic and unconscious has this century produced rich theatre around visual artists. The Secret Death of Salvador Dali begins with the surrealist’s deathbed catching fire and little redemption for the old foul-mouthed fascist. Surprisingly, Sewell says he ended up in love with Dali and his infantile perspective.

In Three Furies Sewell then relished the savagery and sadness of Francis Bacon and the extremities of emotion and homosexuality he shared with his muse and partner George Dyer. Simon Burke played Bacon in its premiere for Sydney Festival 2005. Director Jim Sharman describes it as hallucinogenic theatre, a theatre to transform people.

“The realistic, naturalistic part of the world is actually quite insignificant in any experience,” says Sewell. “That’s what I want on stage – the full complexity, the fantasies, the emotion, the imaginative, the dreams of the world. I don’t want it reduced to a matchbox. It’s a very theatrical idea but then you’re struggling with the stagecraft of how to do it. But Sharman completely understands that moving in and out of fantasy.”

The two then took their hallucinations to film and together made Andy X, about Andy Warhol, but Sewell didn’t share Sharman’s love for this far cooler customer.

Abstraction aside, Sewell’s plays this century have demonstrated a powerful immediacy to the urgent debates and headlines of our time – like American racism, global warming, Olympic drugs and corruption, Australian war crimes in Afghanistan, and how we answer terrorism.

This prolific wave started with his popular thriller, Myth, Propaganda and Disaster in Nazi Germany and Contemporary America (2003), about the end of liberal tolerance and the rise of an Orwellian surveillance in America after 9/11. The epic title came to him in a dream; he took just 12 days to write it.

The US of Nothing (2006), also directed by Sewell, haunts us now in 2020 with its dark comedy about a white family surrounded by 20,000 angry blacks, trapped in the New Orleans Superdome after Hurricane Katrina.

Like so many playwrights, Sewell has long sought a family - a director, a theatrical home to share the long collaborative process of bringing stories to the stage.

“Theatres here,” he says, “are increasingly dominated by exclusive gangs without any doors open to the outside, just the winner takes all. Then they eventually change but the next gang running the institution is just as exclusive.”

For Stephen Sewell though, NIDA has become that next best thing to a professional home. Final year productions have premiered many recent plays and allowed him big cast, big picture epics – just like the old days.

And still he keeps writing. He has high hopes for a new play, A Portrait of You, about Lucien Freud painting David Hockney. His mate Bruce Beresford wants to direct it. And Barry Humphries wants to play Freud.

“I’m also about to begin a big play called Time. It concerns a futures trader making the bet of his life while his philosopher father is dying in the other room. Time. I feel it’s running out, and there’s so much to write.”

Stephen Sewell spoke to Martin Portus for a State Library of NSW oral history project on leaders in the performing arts; the full interview now available on the Library’s website.

Images: Arbus & West - Melbourne Theatre Company (photographer: Jeff Busby); The Boys - DVD cover; Stephen Sewell (courtesy Currency Presss); two photos from the 1983 premiere of Blind Giant in Adelaide - Kerry Walker and Catherine McClements, & Gillian Jones, Robert Grubb, Melita Jurasic and Geoffrey Rush (Photographer: David Wilson, courtesy Currency Press); Ron Haddrick and Janet Andrewartha in the first (Playbox) production of Garden of Granddaughters in 1993 (Photographer: Jeff Busby); Nicholas Eadie and Greg Stone in Myth, Propaganda and Disaster in Nazi Germany and Contemporary America (Photographer: Jeff Busby, courtesy Currency Press)