How Mrs J C Williamson Struck Oil

When Maggie Moore (Mrs J C Williamson) left her marriage for a man fifteen years her junior, she took the theatrical couple’s international hit with her. Leann Richards reports.

In 1894 theatre impresario J C Williamson was a very unhappy man. His estranged wife, the popular Maggie Moore, was touring Australia with the melodrama Struck Oil. Williamson considered the play his property and resented his former wife profiting from it. In addition, she had cast her lover in the role Williamson had made famous.

Struck Oil had catapulted J C Williamson into the highest echelons of fame. Before Struck Oil, Williamson was one of many actors struggling to make a living in the United States. After Struck Oil, he was a successful businessman and entrepreneur, respected around the world.

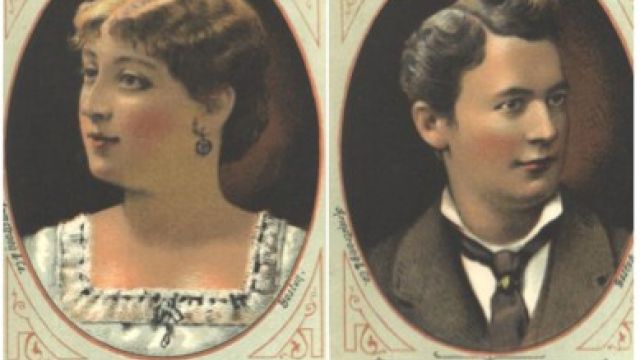

It had all started in 1872. 27 year old James Cassius Williamson, a leading player at the California Theatre in San Francisco had seen a performance by Maggie Sullivan, a star at the nearby Metropolitan. Maggie was a vibrant Irish–American 20-year-old who had started her career as a child. She was a talented and versatile actress and singer and James soon proposed marriage. After initial reluctance, reinforced by her mother’s disapproval, Maggie agreed and Mr and Mrs Williamson became a partnership, on stage and off.

JC was ambitious and soon persuaded a part time playwright to sell him a script. After much tinkering and tailoring of the main characters to suit the personalities of both the Williamsons, the script became Struck Oil.

The melodrama featured two major roles, John Stofel, the kind and sacrificing father, played by JC and Lizzie, his vivacious and tempestuous daughter, performed by Maggie. The play was a hit in the US and the Williamsons were invited by George Coppin to take it to Australia

They arrived in 1874 and caused a sensation. Struck Oil was enthusiastically acclaimed during a slow period in theatrical production. It became a legend in Australian theatre history. After a tour that was extended from 3 months to 6, the Williamsons returned to the United States thousands of dollars richer.

Obviously Australia liked JC Williamson and Maggie. They also enjoyed Australia. 5 years later they returned with the rights to HMS Pinafore. It was the launch pad for the development of a theatrical empire. Williamson vigorously defended his rights to the Gilbert and Sullivan piece and was rewarded with the Australasian rights to the rest of the G and S catalogue. This was the foundation of the JC Williamson ‘Firm’.

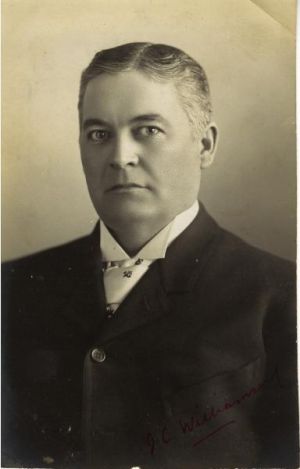

By the 1890s, Williamson was the most famous theatrical manager in Australia. He leased venues across the country, ran the most prestigious theatrical companies on the continent and produced the most popular pieces in the biggest cities. In 1891 he triumphantly brought Sarah Bernhardt to Australia. He was one of the most well known figures in the colony, a man of wealth and high social standing.

So it must have been a shock that just as the divine Sarah was leaving after her earth shaking tour, another woman was also leaving, his wife, Maggie.

A small woman of uneven temperament, Maggie enjoyed a lavish lifestyle. She was good at spending money and JC had provided for her generously. He gave her an allowance of 10 pounds a week and her weekly income grew to 50 pounds a week when she was working. This was an enormous amount of money at the time.

In 1891, JC started complaining about some promissory notes that Maggie and her brother Jim had signed. The notes were worth thousands of pounds. It was the first indication that the marriage was in trouble. Later that year it became clear that the pair had separated, although there was no public acknowledgement of the break.

What led to the situation was never fully explained. Perhaps Maggie’s character, which had caused some problems in the early years of the marriage, had finally become unmanageable. Perhaps JC exploited his power over the chorus girls too often. It was clear, however, that the marriage was permanently over by late 1891, especially after Maggie ran off with a younger man, New Zealander Harry (H R) Roberts.

Roberts was, of course, an actor. He was a tall man with a very impressive voice. He was also young and handsome and 15 years Maggie’s junior. In the early 1890s Harry worked in Sydney and in the city’s close-knit theatrical community it was inevitable that he would meet the wife of the biggest name in the industry. Somehow the meeting turned into a love affair; an affair that was probably well-known in the theatre world, but never revealed to the press.

In the late Victorian era, social status was very important, and Williamson was very conscious of his standing as a leading figure in Australian society. It was this desire for respectability that made him reluctant to publicise Maggie’s behaviour. His profits and business relied on a good reputation; he could not risk it by charging Maggie with adultery.

In 1892 Maggie toured country areas of Australia with her own company. The next year she took Struck Oil to New Zealand. In this version John Forde played John Stofel and Maggie played Lizzie. However, by the end of 1893 Maggie’s company openly billed H R Roberts as its leading man, and in 1894, Maggie twisted the knife and gave Harry the leading role of John Stofel in Struck Oil.

Williamson was incensed. He wrote to his lawyers demanding that they stop Maggie from presenting the play in Melbourne. He was sentimentally attached to the piece and seemed to consider the role of John Stofel as his acting legacy. He condemned Maggie’s conduct as legally and morally inappropriate but was reluctant to expose her desertion publicly.

Williamson later decided against pursuing the matter legally. But it was too late, his lawyers were committed. When the matter came to court, the magistrate expressed surprise that Williamson could not control his wife. Under Australian law at the time, all marital property belonged to the husband, so it was impossible for Williamson to win a case against Maggie based on property rights.

The play went ahead and Maggie ensured that advertising included the fact that she had won the case.

The play went ahead and Maggie ensured that advertising included the fact that she had won the case.

Maggie and Harry played to packed houses and continued to perform Struck Oil for many years. The couple travelled to the US and the UK and had moderate success.

In 1899 during a tour of New Zealand, Maggie finally sued Williamson for divorce. Her suit was based on the fact that he was living with a former member of the ballet chorus, Mary Weir.

Williamson, ever mindful of public opinion, did not contest the action and Maggie was awarded a decree. Maggie and Harry returned to the US and married in 1902. Williamson and Mary also married and had two daughters.

Maggie outlived both Williamson and Harry. She continued appearing on stage well into her 70s. In 1925, a huge benefit performance was held to celebrate her 50 years on the Australian stage. Shortly afterwards she returned to San Francisco where she lived with her sister. In 1926, Maggie died in San Francisco.

Maggie, the small fiery Irish woman, was perhaps the only person in history to exploit J C Williamson. In an era where women had little power, she astutely used her husband’s desire for social respectability against him. Whilst Williamson is acknowledged as a leading figure in Australian theatrical history, few people acknowledge Maggie’s role. Her outstanding stage partnership with him helped lay the foundation for the Australian theatrical industry. She deserves a place in that history as illustrious as that of her former husband.

Images - top images are early images of Maggie and James, lower images date from the early 20th century. From the collections of Leann Richards and Neil Litchfield.

More Stage Whispers History articles

See more articles by Leann Richards at www.hat-archive.com

Visit Leann's blog www.hat-archive.blogspot.com/

Originally published in the January / February 2013 edition of Stage Whispers.