Behind the Scenes at MTC

What makes Australia’s oldest professional theatre company tick? The Melbourne Theatre Company turns 60 this year. Its success has been built on the back of those behind the scenes, who have spent decades stitching, painting and building plays from scratch. Lucy Graham reports.

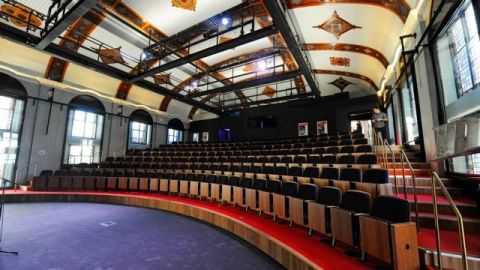

Four pianos are backed up against the astonishing red walls in the corridor. The atmosphere is close and slightly confronting. Turning a corner, we pass rehearsal rooms. Rehearsals for Solomon and Marion are underway.

The corridor opens into a huge warehouse space. Alcoves on two levels accommodate props, a wet area, workspaces and offices. The air is cool, and it feels a little urgent. On the floor, huge boards lie flat, waiting to be of service. Over yonder tall blue scaffolding and a roller-door lead to the loading dock.

This is MTC-HQ.

This is MTC-HQ.

Each year the Melbourne Theatre Company produces twelve major productions, an education program and season of new or independent works. For each, sets are designed and constructed, props found, renovated and crafted, costumes sourced and sewn, and sometimes hats, wigs, and art finishing are required.

Having moved from the ‘old digs’ in Farrar Street, South Melbourne in 2009, MTC’s beating heart is now in Sturt Street, just a stone’s throw from the Southbank Theatres and Arts Centre Melbourne.

Shane Dunn, Scenic Art Supervisor, has been with MTC since 1991. Currently his crew of three is constructing walls, over two-storeys high, for The Crucible set. It is a ‘big, difficult build’.

‘We should be turning shows around every four weeks’, says Dunn. ‘This has taken the carpenters double that [time], so that’s going to impact the shows around it.’

The holdup was caused by ‘a gabled roof and a wall, which sounds simple but it’s diabolically difficult because there’s only one wall holding the whole thing up.’

Invariably there are technical challenges to resolve for every show. Initially the Director and Designer initiate concept ideas. The designer will develop them and create a model and plans. Next wardrobe, carpentry, props, lighting and sound sit around that model with the director and set designer.

‘And we look at it, and shrug our shoulders, and arch our eyebrows, and go, really?’ laughs Dunn. ‘We nut out how we are going to do it. If there are some really big issues the conversations go back and forth for a number of weeks. Once we’ve nutted out those problems, and financially it looks alright, we press a button and off we go.

‘And we look at it, and shrug our shoulders, and arch our eyebrows, and go, really?’ laughs Dunn. ‘We nut out how we are going to do it. If there are some really big issues the conversations go back and forth for a number of weeks. Once we’ve nutted out those problems, and financially it looks alright, we press a button and off we go.

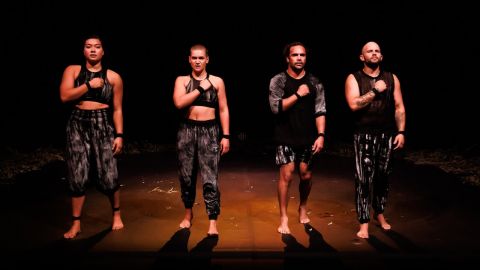

‘Solomon and Marion was relatively straight forward,’ says Dunn, ‘except for the eight cubic metres of sand that has to be landscaped all over the stage. The contours of the stage are covered with carpet, which is simply there to capture the sand so it doesn’t slide off.

‘There are technical problems with every show. In Solomon and Marion it’s turning out to be the painting done by the actor every night as part of the script. How much paint do you need? Between the matinee and evening performance the paint is going to be wet. What are we going to do about that? Well we have to build two, for matinee days, which means you have to get it all down, and off stage, and then bring it back on.’

For the current concern, The Crucible, it’s not sand on stage, but imitation mud made from a combination of rubber, sand, food dye and a wetting agent made of acrylic beads. It’s slippery and damp to touch, but won’t leave the actors wet.

For the current concern, The Crucible, it’s not sand on stage, but imitation mud made from a combination of rubber, sand, food dye and a wetting agent made of acrylic beads. It’s slippery and damp to touch, but won’t leave the actors wet.

‘Its all inert and safe and non toxic,’ explains Dunn. ‘It has to be stable and remain the same for a month. Who knows if we’ll use it – we need a cubic metre-and-a-half. They want it on stage the whole time, and they want people to run through it.

‘Collaboration is fun. You get to work with lot of creative people and solve problems, and that’s rewarding,’ says Dunn.

Props Supervisor Geoff McGregor, a trained architect, has been with MTC for 31 years. His workspace resembles a Collectables Shop. McGregor shows me a photo album of props from years past, describing how items are renovated for particular shows, or made from scratch. He indicates one chair that has been recovered six times.

‘I might have made one hundred beds in my life but they’ve all been different. That’s the good thing about this job. There’s a lot of pressure because there’s only the two of us. Quite often we’re working on four different shows at once.

‘I couldn’t see myself doing any other job but this one,’ says McGregor.

Upstairs, wardrobe manager Judy Bunn, a former cutter, says one of the keys to her job is thinking ahead.

‘We generally have five weeks before rehearsals start,’ reveals Bunn. ‘The costumes have to work with what the actor will be doing. Hopefully we don’t have to completely discard costumes we have made, but sometimes that does happen. We just have to get over that.

‘For The Crucible I was looking at this two months ago and thinking I’m going to need an art finisher, and this number of people to make the costumes. So you’ve got to have projections, and look at everything, maybe talk to the designer to get some idea where they’re heading. Then the buyer and the designer start shopping, and that’s quite intense for a number of weeks.

‘Our buyer, Lucy Moran, goes all over Melbourne,’ says Bunn. ‘She’s been here 25 years and really knows what she’s doing. We need suppliers who’ll operate on a return basis because we get maybe five garments for a fitting because we need the variety, but we’ll only need one.’

The Crucible is set in the 1690s, so latchet shoes (that have no left or right foot) have been sourced from America. Shoemakers Brendan Dwyer in Melbourne, Jess Wootton in Prahran, and Rocco in Malvern are also making shoes for the cast of sixteen, who all require particular footwear.

The Crucible is set in the 1690s, so latchet shoes (that have no left or right foot) have been sourced from America. Shoemakers Brendan Dwyer in Melbourne, Jess Wootton in Prahran, and Rocco in Malvern are also making shoes for the cast of sixteen, who all require particular footwear.

In the laundry area, complete with dying vats, washing machines, and a drying room, an art finisher has been engaged to distress the fabrics to achieve a raw look.

‘She’ll use dust, polish, schmutzstik - an aging crayon,’ says Bunn. ‘Art finishing is an art. You can get some really fantastic effects.’

MTC’s extensive wardrobe collection is impressive. ‘The Good Room’ is a collection of particularly prized items not available for general hire. Some items have come as donations from the public, including an exquisite coat featuring detailed hand embroidery, used in Hamlet.

‘Donations are valuable,’ says Bunn, ‘but they have to be quite what we want.’

Beyond ‘The Good Room’ a large space is hung with rows and rows of garments. Shoes, sorted into colours and sizes, occupy large box-shelves along the wall. This collection is available for hire, and vintage, period shoes and suits are in particular demand.

‘One of our cutters, John Molloy, has been here forty years,’ says Bunn. ‘He would probably know all the suits and the menswear in this room, because he probably made it. It’s an incredible commitment to the MTC.’

‘One of our cutters, John Molloy, has been here forty years,’ says Bunn. ‘He would probably know all the suits and the menswear in this room, because he probably made it. It’s an incredible commitment to the MTC.’

Period shows mean millinery comes into its own, and the services of Phillip Rhodes are a valuable asset. I am shown a crown made for Queen Lear using water-jet cut leather.

‘We were really amazed when we saw this,’ murmurs Bunn, ‘because it opened up possibilities for us. Leather is easy to cut and easy to mould. It’s quite light.’

In an adjacent room Jurga Celikiene makes wigs, knotting individual hairs according to the specs. It is eye-crossing work, even as she works with two lights. When we enter she is working to add hair to an existing wig.

‘This wig has already been in two shows,’ Celikiene explains. ‘First I made it for Richard III - it was short, and this other one is longer, so now I need to add hair. Luckily it doesn’t need to be very full or it would take too long. Now I will cut it and it will be alright.

‘It’s all real hair. We barely use synthetics. Often I buy cheap wigs for hair stock. Grey is the hardest because it’s not natural. If you buy hair it is about $120 for 100 grams maybe. If it’s natural grey, oh my god, its thousands! European hair is really expensive - it is much finer. Asian hair is thicker.’

And if someone wanted to donate hair to you?

And if someone wanted to donate hair to you?

‘Oh I would be most appreciative. For men’s wigs its crucial to have European hair; it always looks much better. For women’s wigs Asian hair is not so bad because it is usually fuller and longer.’

Beyond clothing and accessories there are maintenance issues to be resolved. Judy Bunn shows me a pair of shoes used in Richard III.

‘Because Ewen [Leslie] was meant to have a limp, he dragged his shoe,’ she recalls. ‘That happened every night so in wardrobe maintenance we’d have to build the shoe up again so he could wear it down again.’

And then there are the costume effects that call for the use of alternate materials, and innovative problem solving.

‘In Return to Earth, we had a character that was meant to grow barnacles. He had a pair of overalls on and he had barnacles across one shoulder. So that’s cast in a silicone. They had to be removable – the girl in the show picked them out. But they got infected in the show so we had to make another one really gross and infected. You can imagine school groups really love this.’

‘In Return to Earth, we had a character that was meant to grow barnacles. He had a pair of overalls on and he had barnacles across one shoulder. So that’s cast in a silicone. They had to be removable – the girl in the show picked them out. But they got infected in the show so we had to make another one really gross and infected. You can imagine school groups really love this.’

‘In Return to Earth [a character] had to get pregnant in seconds. So what they came up with downstairs was a beach-ball inside a little bather with a tube that came round the back to a little pump the electrics men sourced from Canada. It’s actually a blood pressure pump. It was activated remotely off stage. ’

As I leave MTC-HQ I have a sense that I want to make a contribution to this iconic company. Suddenly donating my own hair doesn’t seem such a crazy notion.

Originally published in the July / August 2013 edition of Stage Whispers.